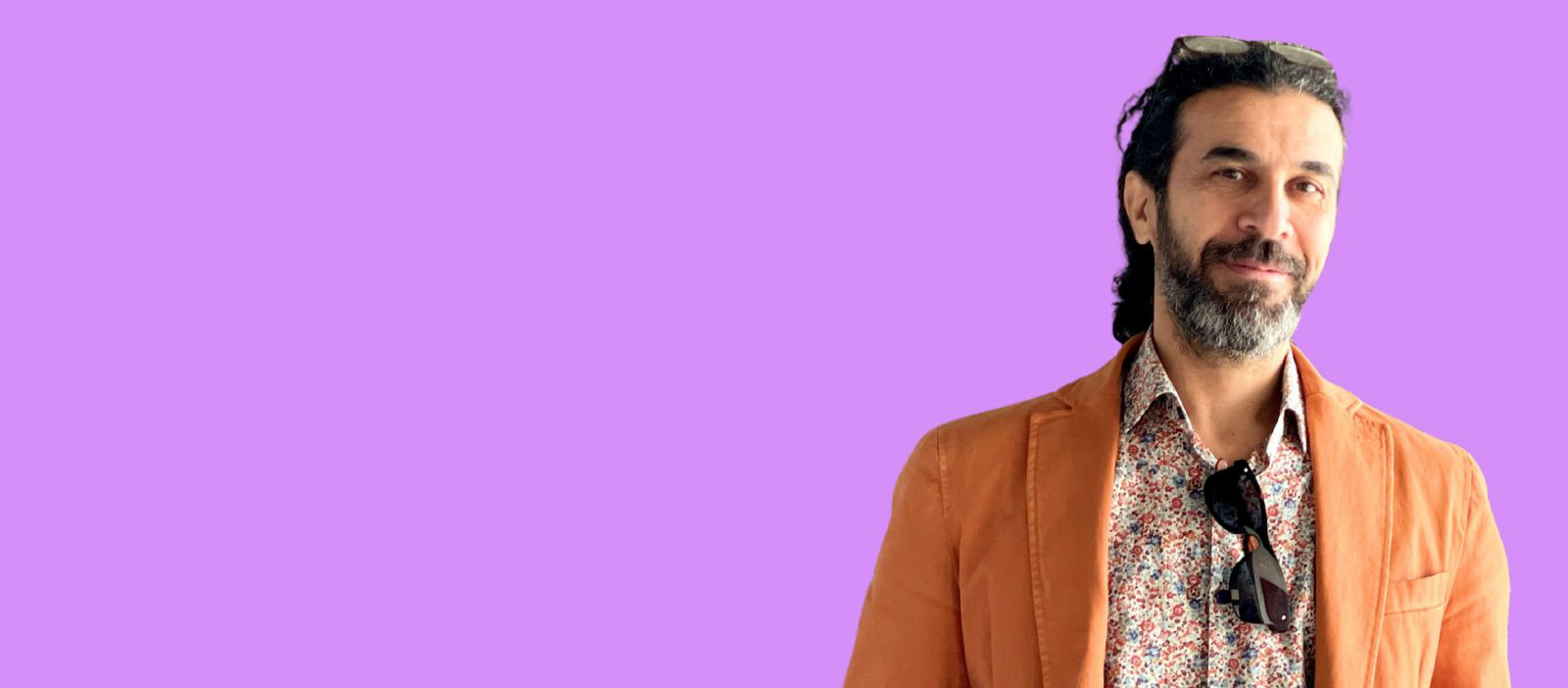

Shorsh Saleh: ‘You have to find your roots in order to make art’

Artist and carpet weaver Shorsh Saleh’s mixed media works have been exhibited around the world. Photograph courtesy of Shorsh Saleh

The artist and carpet weaver uses his craft to tell stories of migration, inspired by his own experience after facing years in limbo in the UK’s asylum system

Shorsh Saleh is an artist and carpet weaver who uses his craft to tell stories of migration, inspired by his own experience. In 2000, during the aftermath of the Iraqi-Kurdish civil war, 23-year-old Saleh left his home and family in Iraqi Kurdistan in search of a more stable future.

He arrived in the UK in 2002 when, in the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq, the Home Office was offering asylum to Iraqi citizens. However, Saleh’s application fell through the cracks and it wasn’t until 2010 that his case was finally accepted.

He used that time to deepen his art practice, focusing largely on miniature painting and sculpture, and went on to study at the School of Traditional Arts in London. He has since joined the institution as a teacher of carpet weaving, with a particular interest in tribal designs and village patterns.

His mixed media work has been exhibited around the world, including at the Royal Collection Trust, The King’s Foundation, British Museum and Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia. He currently has three pieces showing at the Migration Museum in London, including Waiting II, an installation inspired by his own eight-year asylum case.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Where does your love for art and mixed media come from?

My older brother was a self-taught artist. He was very creative and just did all kinds of things — one day he’d be painting, and then the next day he’d be making some kind of sculpture. I was always hanging around with him to see what he was doing, and sometimes he would give me brushes.

When I was 19 I joined an art organisation in the city of Sulaymaniyah. We did some group shows, but at the time my work was just copying western styles without having a lot of originality or direction. With modern education, everything is westernised. If it’s not validated in a western institution, then often it’s not considered art.

Once I moved to London and started studying, I became more interested in miniature painting. I was also researching Kurdish visual culture, and realised that the only visual designs we produce are our carpets. I had a Persian classmate who taught me how to properly weave, and I completely fell in love with it. So for my final project I produced a carpet in the style of a miniature painting.

What’s the first thing we should know when it comes to understanding carpet design?

We all know what a carpet is — why it’s made, the materials used and the purpose it serves. These details are all familiar. But the secret is in how you make a carpet. My teaching now focuses on the motifs and techniques used in tribal carpet designs because I find they are more true to their origin and more authentic than city carpets.

Carpet making, which holds great significance in our Kurdish ancestry, is also very therapeutic. Whenever you are stressed, just grab a loom and start weaving for 10 minutes. Your mind will be completely cleared.

You have several pieces on display at the Migration Museum. What inspired this project?

There were a lot of ups and downs after I left my home in Kurdistan. I travelled through dangerous countries, and I was homeless for some time. I had a lot of ideas that came to mind inspired by the journey, but I didn’t have any paper or paint with me, so I used to carry a small notebook where I could write these ideas down. A lot of them later became paintings.

I waited eight years for my asylum application to be accepted, so I had a lot of space to study art. I was moved around between six different cities, from Birmingham to Halifax. Each time you apply to a new court, you have to wait a year just to get another hearing. And during that time I wasn’t allowed to work or travel. I got some benefits, but I mostly had to rely on friends.

My piece Waiting II was directly inspired by that time waiting for an asylum decision. It includes a series of chairs made up of different shapes and layouts, slowly sinking into the ground.

Has exploring displacement through art helped you process your own experience?

If you come from a different background, you have to find your roots in order to make art.

For many years, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to make art on subjects like migration because it can be very sad and I didn’t want to bring sadness to other people. But then a friend made me realise that a lot of people aren’t aware of what’s going on, and that through art I can share the experience and make people empathise with the subject more.

Since then, whenever I try to make any art, I purposefully respond to my own stories and bring in a cultural element, so that when people see the work they know where it’s from. Art should respond to all the cultural elements of society. People communicate with that. It’s what remains. It’s also helped me be very honest with my art.

Shorsh Saleh’s Waiting II is on display at the Migration Museum’s All Our Stories exhibition. On 15 February, he will be leading the British Museum’s Crafting the Silk Roads workshop.

Newsletter

Newsletter