The NHS winter crisis shows why Labour needs to urgently reform social care

As a doctor in elderly medicine, I have seen patients wait weeks to be discharged — sometimes exacerbating their healthcare issues

Social care has slowly become a spectre that haunts every British government. In the 2010 general election, the Tories attacked Labour’s idea of a so-called “death tax” to fund social care for the elderly. In the 2017 general election, it was Labour that returned the favour by criticising Theresa May’s now infamous “dementia tax”. While there has been a cross-party consensus for decades that something needs to be done to address Britain’s social care conundrum, both Labour and the Conservatives have failed to put anything into action.

Each year, a new set of statistics reaffirms the worsening crisis that faces us all. Over the next 15 years, the size of the UK population aged 85 or over is projected to increase from 1.6 million to 2.6 million, according to the Office for National Statistics. The projected social care cost is going to almost double to £16.5bn by 2038, based on current spending. The NHS is already overwhelmed; it is hard to imagine how dire things will look if nothing is done.

It is health professionals like me who see the tragic effects of two decades of inaction on social care in hospitals. In April 2024, almost half of all delayed discharges were due to waits for care home beds or home-based care, according to the Care Quality Commission, the independent regulator of health and social care in England. Working as a doctor in elderly medicine, it is not uncommon to see a patient’s discharge delayed for up to three weeks while awaiting the appropriate social care for them to be discharged safely.

There have also been times where the delay in social care for these patients inevitably leads to them catching infections such as hospital-acquired pneumonias. This delays discharge even longer, and these infections can sometimes be more dangerous than the reasons for admittance. It also means elderly patients are forced to endure more blood tests, scans and courses of treatment, which can be demoralising.

During the winter crisis this year, we are seeing “corridor care”, as it is referred to, become a common sight in emergency departments across the country. With flu spreading rife throughout the UK, hospital beds have been full and chronic defunding of both hospitals and social care has left the health service on its knees. With patients unable to leave the hospital while awaiting a suitable placement, this has added further strain to the NHS, leading to poor flows of people through A&E and onto wards — as acknowledged during last year’s damning Darzi report, which said the NHS was in “critical condition”.

It is difficult watching people suffer when waiting to leave — and similarly tough to see patients in the emergency department, as well as their family members, become increasingly distressed while waiting for a bed. It is putting doctors like me in the most frustrating position.

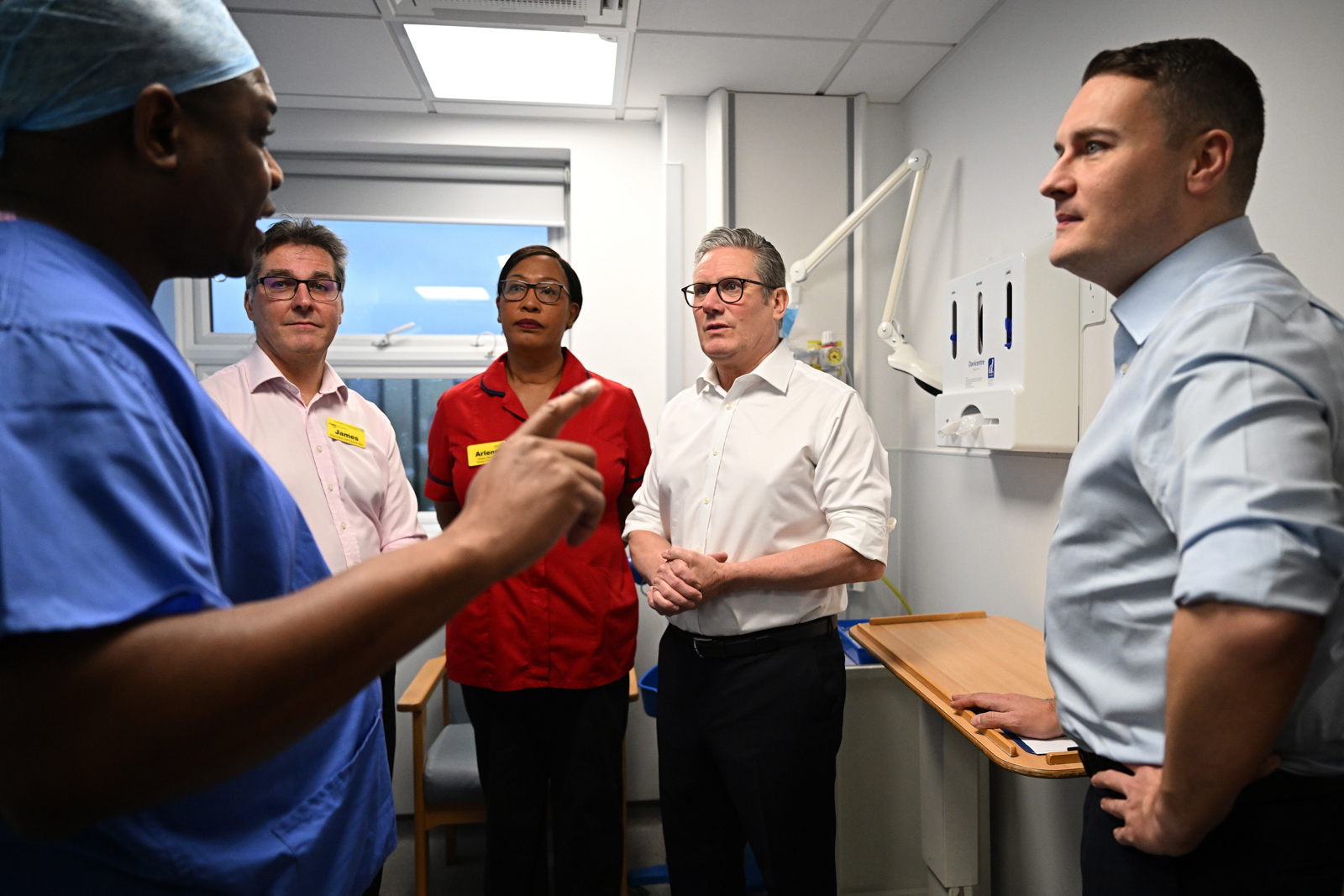

Quite clearly, things cannot go on as they are. Yet the government’s plan, in essence, is to do exactly that. Yet another independent commission into the scale of the social care crisis and possible solutions, announced this month by health secretary Wes Streeting, is due to start in April and expected to finish in 2028.

Councils and care providers were quick to say the review would take too long for the well overdue reform of services already on their knees. But it is not just health professionals or patients who are concerned about the delay: Sarah Woolnough, chief executive of independent thinktank The King’s Fund, has stressed the importance of action now rather than later.

The scale of the problem is frightening, even before we acknowledge the shortage in NHS staff, which currently stands at more than 150,000 and requires large numbers of economic migrants to fill the gaps. This does not bode well for a country where all of the main parties agree that migration needs to be significantly reduced. It would be foolish to think this crisis can be resolved without the need for overseas workers — they are imperative to fixing it. The government has legislated for a small pay rise for care workers, but such a large number of vacancies is going to require more incentives to attract the staff required.

This is not an issue that can be kicked down the road. Patients and their families are suffering, while healthcare professionals are unable to deliver the help they need. I fear that delaying social care reform further could backfire immensely on an already unpopular Labour party, who could find themselves out of government before implementing any of the changes Streeting’s review might suggest.

Investment in social care is needed now and is vital to the NHS functioning for the next decade. Doctors and patients should expect better from the self-proclaimed “party of the NHS” in resolving a crisis they have had 14 years in opposition to prepare for.

Newsletter

Newsletter