Muslim families are battling to get their autistic children diagnosed

The number of children waiting for an autism assessment has reached a record high, with ethnic minorities among the hardest hit

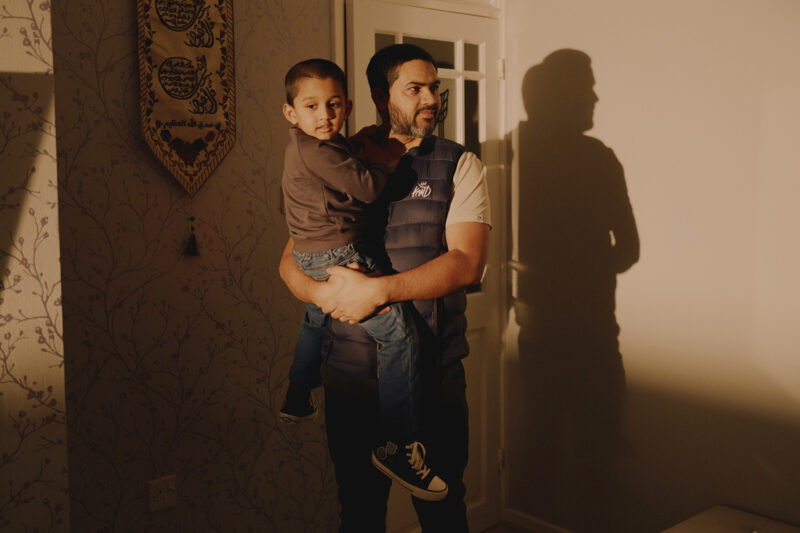

Bushra Alakraa is certain that the only reason her daughter, Laila, was finally referred for an autism assessment was because the health visitor who picked up the phone that day was Muslim.

For two years, the 32-year-old mother of two had repeatedly told her GP and health visitors that she believed Laila, now almost six, had autism. She had noticed her daughter was showing signs of extreme anxiety and that she was semi-verbal — common symptoms experienced by autistic girls.

“As a parent, you just know when something’s not right. We could tell from when Laila was born that she was dysregulated,” Alakraa said.

She added that her London-based GP told her she was being overly cautious and that her daughter did not qualify for an autism assessment, reflecting the experience of many parents across the country who feel the system is now failing their children amid rising cases of late and misdiagnoses. It was only when Alakraa spoke to the Muslim nurse that she felt she was taken seriously.

“She said: ‘I can tell how distressed you are and I’m going to get you the help you need,’ and referred me to community paediatrics. That’s when we saw them and they said: ‘Yes, you qualify for an autism assessment.’”

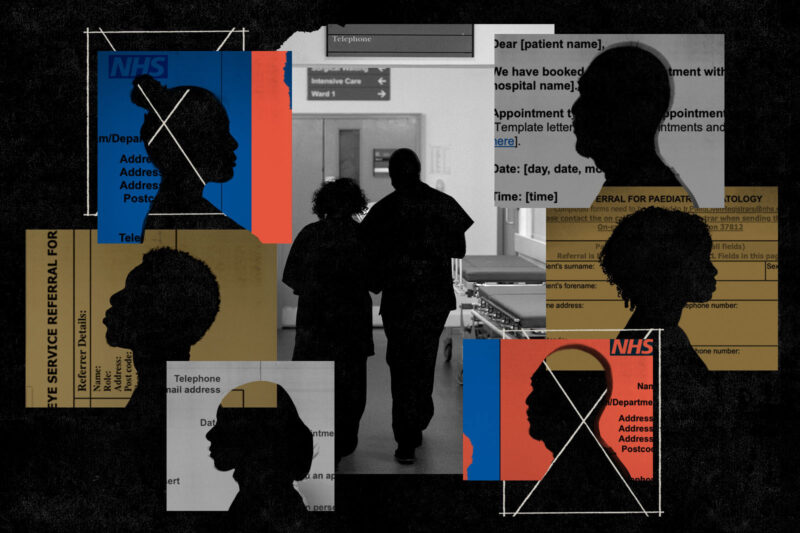

The number of children waiting for an autism assessment has now reached a record high since Covid, in what has been described as a “crisis” for autistic children. Issues including increased demand, social inequalities, and underfunding and understaffing at the NHS have meant thousands of autistic young people have had to wait months or even years for health and education support, according to research from the Child of the North initiative published in 2024.

Since 2020, the number of children waiting for an assessment has risen by 306%, from 35,000 to 143,119 in June 2023. In England, the national target for beginning an autism assessment is three months, but fewer than 10% of children start the process within that time period. In fact, one in six children waited more than four years for a diagnosis via the community health service route.

The issue is particularly acute for families from Black, Asian and ethnic minority backgrounds, with many having reported feeling discriminated against by health services or local authorities. What’s more, lack of research into their experiences has made it harder for autistic people from these communities to get the support they need, according to the National Autistic Society.

Privthi Perepa, associate professor in autism studies at the University of Birmingham, is one of the few academics in the UK who has researched the discrimination faced by minority families with autistic children.

He found that in 2021-22, schoolchildren from Pakistani and Indian backgrounds were less likely to have been registered as autistic than their white British counterparts.

This disparity in autism diagnosis mostly affects those who live in deprived areas, and is largely driven by racial bias and having English as a second language, according to Perepa.

“If the parents have any kind of foreign accent, the typical way is to treat you like an idiot,” he said, adding that there are currently not sufficient tools and standards in place to assess and diagnose autism in bilingual children.

Though Perepa did not identify the pupils’ religions in his research, Muslims are believed to be disproportionately affected. For example, more than 92% of Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in Britain are Muslim, while 40% of the country’s Muslims live under the 46 most deprived local authorities, many of which have been affected by significant budget cuts, including in support for children with special educational needs.

In interviewing 22 parents and carers of autistic children from ethnic minorities, Perepa found that healthcare professionals were making assumptions on “how you would understand or not understand information” if you are visibly Muslim.

Indeed, Alakraa believes that being visibly Muslim played a role in how she was treated by healthcare professionals and teachers at her daughter’s school. Her daughter has still not received specialist learning support because of her local authority’s refusal to grant an educational healthcare (EHC) plan — the legal document outlining the tailored support required by children with additional learning needs. It stated that her autism symptoms were not “severe enough”, Alakraa said. She is now working with Sunshine Support, an organisation providing legal advocacy for parents of children with special education needs and disabilities, and hopes to appeal for an EHC plan.

“I think being Muslim and hijabi, you get taken less seriously,” she said. “Sometimes we get spoken down to. I think there’s this assumption that we’re ignorant and we don’t understand what we’re talking about. You have to push a lot harder and be a lot firmer. You have to almost prove yourself.”

Dr Chris Papadopoulos, principal lecturer in public health at the University of Bedfordshire and founder of the London Autism Group Charity, agrees that discrimination “contributes to the late diagnosis or misdiagnosis we see in autistic adults in the Muslim community”.

The average waiting time for an autism assessment for adults is 323 days, according to NHS data from 2023.

Papadopoulos speaks to Muslim families with autistic children regularly at the community meet-ups the charity holds every weekend. “Often, the families feel like they’re not being heard,” he said. “They don’t feel that the GPs and professionals take them seriously, especially if they’re from ethnic minority backgrounds and especially if they’re female. They’re told they’re complaining for nothing or they don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Zynab Al Bahrani, 34, changed career last year to train as a consultant for autistic and neurodiverse families after her own difficult experience in obtaining an EHC plan for her autistic son. Though she believes late diagnosis or misdiagnosis is largely driven by a lack of government funding, she said there must be more research and awareness of the particular issues facing minority communities.

“As a whole, when it comes to disability groups, we know that people who come from ethnic minorities have an added layer of difficulty with accessing services because of cultural differences and language barriers,” she said.

In April 2023 NHS England published guidance to improve autism assessment services across the country. The government is currently considering the next steps to improve diagnostic assessments and support, according to a spokesperson from the Department of Health and Social Care.

“We are determined to reduce waiting times and ensure all autistic people, regardless of background, can access high-quality care and support more quickly,” they said.

“The government is committed to addressing disparities and ensuring all communities have equal access to healthcare, and through our 10-year health plan we will transform the NHS and make it fit for the future.”

Newsletter

Newsletter