Luton’s Muslim Vauxhall workers ‘devastated’ by plant closure

The Bedfordshire town is home to one of Britain’s largest Muslim communities, and many have worked at the factory for years. They want the government to step in

Muslim workers at Luton’s Vauxhall factory this week said they were “devastated” by its looming closure and felt like they were “just numbers”.

And they warned that a wave of unemployment could compound existing inequalities in the town, whose Muslim community is one of Britain’s largest and makes up about a third of Luton’s population.

The multinational car firm Stellantis, which owns Vauxhall, announced in November that it planned to close its Luton plant in April 2025 and shift production to another factory 180 miles away in Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, leaving about 1,100 people at risk of losing their jobs.

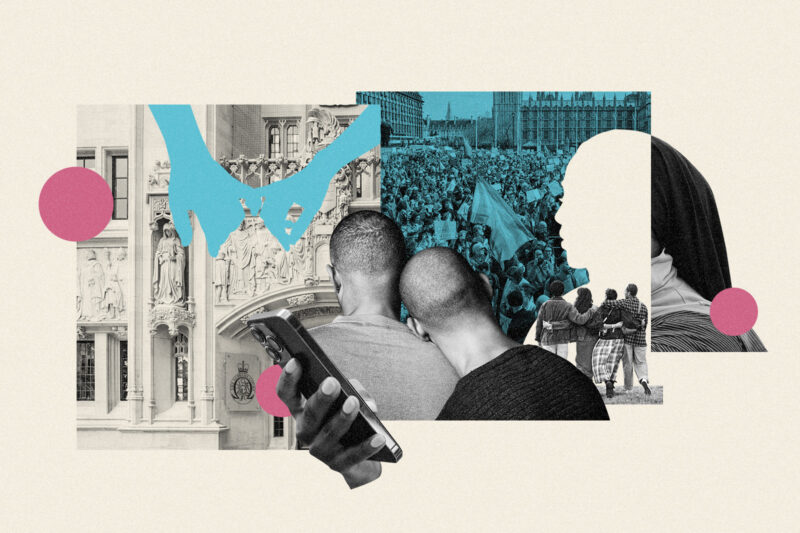

Workers and their supporters gathered outside the factory on Wednesday to put pressure on Stellantis to reverse its decision. If it goes ahead, the closure will end nearly 120 years of manufacturing operations in the Bedfordshire town.

“We have loads of Muslims working within this factory,” said Mohammed Hussain, a rep for the union Unite, who has worked at Vauxhall for more than 15 years. Many Muslims in Luton will also have had parents or grandparents who worked at the plant, he added.

Hussain described feeling “disappointed” about the decision and expressed concerns that job losses would deepen inequalities in the town. Muslims in England and Wales are already more likely to face unemployment than the rest of the population, with 2016 parliamentary research identifying discrimination as a factor. Research from Luton council in 2022 found that ethnicity was a barrier to career progression within the local workforce.

“This is a big employer in Luton and if it closes, where do we go?” asked Hussain, whose Vauxhall job provides his family’s main income. “A lot of people think, ‘at least you’ve got Luton Airport’. But you’ve got over 1,000 people leaving or being made redundant at the same time. And then you’ve got the agencies and all the suppliers. It’s massive. This community will suffer, without a doubt.”

He praised the support he and his colleagues have been receiving from neighbours. “I’ve had a lot of calls from businesses, taxi drivers and bus drivers,” he said. “A lot of the local mosques have also shown solidarity with the Vauxhall workers.

“Working at the factory has been amazing — it’s been nice to have diversity and harmony. The closure will impact us a lot because Vauxhall has supported the work of diverse communities in Luton.”

According to the 2021 census, the number of Muslims in Luton grew 48% between 2011 and 2021, to 74,191.

Zafar Iqbal, a worker on the production line at the factory, told Hyphen he was “devastated” and that the closure is “a big loss for employees and the people of Luton”.

“We’re trying what we can to keep the factory alive because it’s very hard to find any jobs in Luton and it’s going to affect a lot of families trying to put food on the table,” he said.

Iqbal, who has worked at the factory for almost a decade, criticised Stellantis’ treatment of its Vauxhall workers, accusing management of not caring. “We’re being treated like we’re just numbers,” he said. “There was no care, no discussion. One day you’re working and suddenly it’s like, ‘this is what’s happening’. It’s completely out of the blue and we didn’t understand.”

Another worker, Habib, who asked us not to publish his surname, agreed: “Everybody’s so shocked. This is a big company in Luton and so many people from the town work there — many with families to support.”

Habib told Hyphen he was particularly concerned about the factory’s younger employees. “I know some older workers have been considering retirement or voluntary redundancies. But for young workers, it’s going to be especially hard.”

Lewis Norton, a national organiser for the automotive sector at Unite, echoed Habib’s concerns. “Some guys might be on the right side of 55 to look at redundancy payments and packages,” he said. “They might be lucky enough to be homeowners, and might have limited time left on their mortgages. But for the younger generation who work here, it’s just another industrial site in Luton that’s going to close with no jobs to replace it.”

Stellantis has blamed the government’s zero-emission vehicles rules, saying that “challenging” electric vehicle quotas played a “significant part” in its decision to shut down Luton production.

But Norton puts Stellantis’ decision down to “greed”. “They have a workforce that is producing vehicles for a really cheap price and they are making exuberant profits,” he said. “The problem with that is the consumer now is unwilling to buy vans retailed at £35,000.” He described cutting the plant as “one final Hail Mary to try and save a few quid”.

There may yet be hope, however. Speaking to Hyphen following a meeting with business secretary Jonathan Reynolds, Gary Reay, a Unite union rep who has worked at the factory for 33 years, said the discussion had gone “positively”. On Thursday, Reynolds confirmed that he had written to Stellantis to urge the withdrawal of the redundancy notices, and to make clear that the government is prepared to work with the company to save the plant.

Newsletter

Newsletter