Anti-knife crime campaigner Hawa Haragakiza: ‘If I can protect even one child, that gives me some comfort’

Hawa Haragakiza set up Tamim’s Legacy, a grassroots charity that tackles knife crime, in honour of her son. Photograph by PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Tamim Ian Habimana was stabbed to death on his way home from school in 2021. His mother has since dedicated her life to tackling youth knife crime and founded a charity in his legacy

On 5 July 2021, Hawa Haragakiza’s life changed for ever. On his way home from school, her 15-year-old son, Tamim Ian Habimana, was fatally stabbed in Woolwich, south-east London.

“He was a mummy’s boy,” says Haragakiza. “He was a beautiful son. Really handsome and loving. He had loads of friends. I didn’t know just how much he was loved until after he passed.”

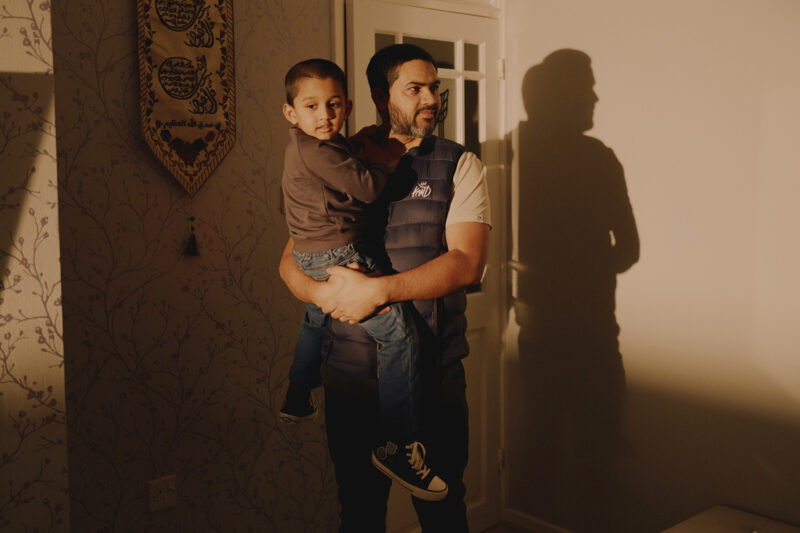

Three years on, the loss of Tamim continues to have a profound impact on Haragakiza and her two sons, aged 16 and 14. “They were all close. There is still a big hole in their lives, but we just keep talking about Tamim and continue to process our feelings,” she says.

Several months after Tamim’s death, Haragakiza set up Tamim’s Legacy in honour of her son’s life, a grassroots charity tackling violent crime. She aims to educate young people in her community about the realities of knife crime and to support victims and their families.

In December 2024, Haragakiza, 35, was awarded the Founder’s Choice Award at the Muslim Women Awards for her campaigning work.

Here, she speaks to Hyphen about keeping her son’s memory alive.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about the motivations behind Tamim’s Legacy.

When Tamim passed away I knew I had to do something. I just didn’t know how. People from my local community showed me how to create an organisation, which became Tamim’s Legacy. It’s not just about Tamim, but also about his friends. I want them to be safe and to have someone to come to if they’re having any issues. There are too many young people who don’t have anything to do after school, so they’re just roaming the streets and getting into trouble. They also don’t have anyone to talk to, so I’m creating that safe space for them.

Tamim’s Legacy is also for other mothers who have lost their children to knife crime and it provides a space where they won’t feel any judgment. I want them to know that they have support too, because the parents need it just as much. When Tamim died, many people thought he must have been involved with a gang, which he wasn’t. That’s the first thing they saw. But just because he was stabbed, it does not mean he was a bad boy. He was a really good boy.

What do you hope to achieve with the organisation?

My aim has always been two things. Firstly, I love talking about my son. I never want him to be forgotten, because his life mattered. Every time I do something under Tamim’s Legacy, it’s a way of keeping his name alive.

The second thing is protecting young kids. I know the pain I feel, and I don’t think I’ll ever truly feel OK again. But if I can protect even one child, if one kid listens and takes something away from what I do, then I’ll feel like I’ve tried and succeeded in helping. That gives me some comfort.

Can you tell us more about the initiatives you’ve developed through Tamim’s Legacy?

I run workshops with Greenwich council and go into schools, mostly in south-east London, giving talks on how knife crime affects families, communities, teachers and friends. We signpost children towards help if they’re in trouble or need help with any other issues. I make sure they know I’m here for them and so are the council, authorities and teachers.

I also run a support group for the kids in my local community, some of whom were friends with my son. We speak twice a month on Zoom and we discuss everything from school, life to friends and work. If there’s anything they see that’s not right, they can share it with me and we can work together.

How should the government and local councils better address the issue of youth violence?

I think the authorities, especially the government, need to listen to communities more. The people on the ground are the ones making real change happen. But too often it all comes back to budgets. You hear promises and plans for good things, but then it’s always, “There’s no budget for that,” and that’s the end of it. That said, there are organisations out there doing amazing work, like the Damilola Taylor Trust, set up in memory of another young boy who was killed, and they do get some financial support, but I think there should be more.

Your work is centred in your community, but have you ever faced any challenges as a Muslim woman campaigning on the issue of knife crime?

I was judged a lot by people from my Burundian community when I began the organisation. There was a lot of confusion as many believed I was getting involved in politics, which they didn’t consider halal. I faced a lot of backlash but, over time, Muslims and other communities have seen my actions and recognised that they align with what is halal. Perhaps Allah is using this to teach us not to judge too quickly, but rather to wait and see His plan unfold.

How do you reflect on the impact of Tamim’s Legacy so far?

The wider impact has been really positive. But at the same time, on a personal level, it can be overwhelming. It’s emotional for me and I often find myself wondering, “Am I doing enough?”

Mothers who’ve lost their children come to me and share their stories, and while I want to support them, it’s incredibly hard for me. After talking with them, I’m often so emotional that it’s hard to focus on anything else. It’s a lot to carry, and sometimes it feels like too much. To cope, I pray a lot, and I’ve also done some counselling. But honestly, I find praying, reading the Qur’an and connecting with my faith helps me more than anything.

Newsletter

Newsletter