Kazim Ali: ‘I don’t stake a claim to being Muslim with a capital M, but it’s what I will always be’

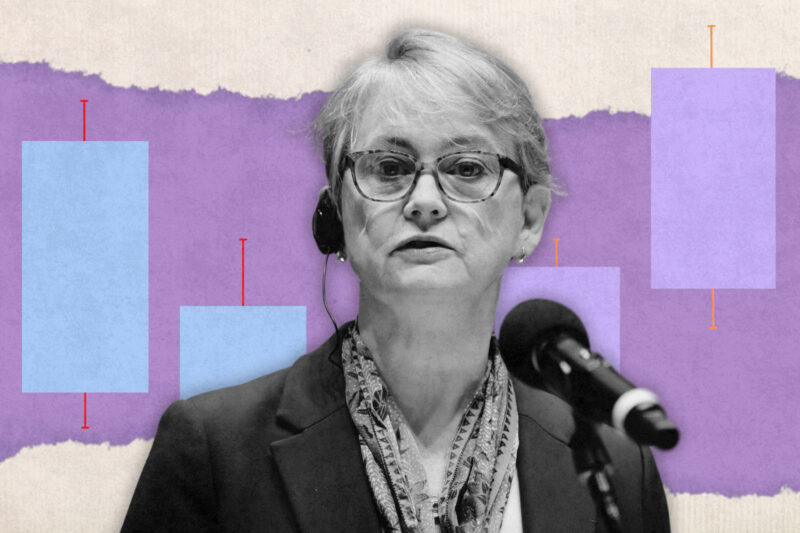

British-born author Kazim Ali is a professor of literature at the University of California and has written 24 titles to date. Photograph by Jesse Sutton-Hough

The author and poet on his relationship with writing and religious identity

When it comes to writing, Kazim Ali is a Jack of all trades. The award-winning author has published 24 titles to date, encompassing works of poetry, non-fiction essays and novels. His books frequently explore spirituality, belonging and queer identity, and are known for their raw and curious tone.

Born to Muslim-Indian parents in the UK, Ali, now 53, spent part of his youth in India, Canada and then New York state, where his family eventually settled.

He began writing in his late 20s and in 2003 co-founded Nightboat Books, an independent, nonprofit literary press. His latest novel Indian Winter, published earlier this year, tells the story of a queer writer struggling to let go of the regrets of his past while travelling through India in search of new friendships and intimacy.

Ali is currently Professor of Literature at the University of California, San Diego. He spoke with Hyphen about his journey as a writer and his personal understanding of faith.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Did you always know you wanted to become a writer?

I’ve always had a relationship with language. Even when I was really young, I used to love the act of writing. Often in my colouring books, I’d write words, but I don’t think I knew what it meant to really be a writer. Then, when I was 16 years old in high school, we read James Joyce and I fell in love with his stories.

I grew up in a typical South Asian family where, as far as professional career paths go, humanities and liberal arts are not included. I worked in social justice organisations after college, but I didn’t really like it. I moved back to New York to figure out what to do next, and it was there that I really started reading poetry and writing again. I had this moment when I realised, the only time you’re ever truly happy is when you’re writing, so maybe that’s what you should be doing.

Your latest novel is set in India and much of your work explores identity. Is that linked to your experience living in different countries?

I was definitely marked by it, not just by being in those different spaces but also when it comes to language. When we went to India, there were four or five languages being spoken in the home. My father tells me I would use words from all of them. I didn’t know they were different; I would just speak them all in a jumble.

I’m not English, but I was born there. I am Indian by culture and ancestry. I’m Canadian. My first memories were in Canada — it’s where I learned how to read and write. And then I’ve lived in the States since I was nine years old. I always tell people that I’m from nowhere. I don’t feel any single national identity in that way.

Did growing up in a Muslim household inform your work in any way?

It’s had a huge impact — dealing with eastern spiritual traditions, the secular culture that I grew up in, the Sufi side of Islam. I was wrestling with all of that constantly. I was very interested in metaphysics, and trying to engage with these experiences through language.

My first few books of poetry are deeply philosophical and engaged in trying to understand the world and get to the truth of things. It was only a few years ago that I started to write more broadly. We grow and we change, so at some point I will likely go back to those themes with a new perspective.

I did feel the responsibility of trying to engage with Islam, but I was dealing more with the edges of the Muslim experience. There’s a time to share and a time to keep quiet, and that’s my time now. There are so many other young Muslim writers being published now as well. There’s Fatimah Asghar and Kaveh Akbar. I don’t know what their relationship to Islam is, but they certainly write about it in their own ways.

How has your own journey with faith evolved throughout the years?

For a long time, I held on to my identity as a Muslim. It was really important to me, and I didn’t want anyone to take it away. Especially as a gay person, I didn’t want to be told I couldn’t be Muslim — although I was told that by pretty much everybody.

I’ve never really wanted to be part of the communal experience of Islam. My relationship with it has always been individual. There are organised communities of gay Muslims and trans Muslims that meet and do retreats. I’ve been to some of them, but it’s just not the way I experience faith.

At this point, I feel it’s better for me to keep having those spiritual experiences privately. I don’t need to convince anyone anymore. I don’t stake a claim to being Muslim with a capital M, but it’s what I will always be. My father whispered the call to prayer when I was born; I feel that sound found a firm place in my brain.

You’ve been teaching literature for more than two decades now. What do you find most nourishing about this work?

Everyone comes in with their own life experience, their own background, fears and joys, their unique approach to writing, what they want to do and who they want to be. It’s kind of incredible to be a part of that.

I still remember my first class at a local community college in New York. I gave them a writing prompt, they wrote for a little bit, we shared, I gave feedback. It was fun and exciting. At the end of the class I remember thinking I could do this for the next 50 years and never get bored.

Newsletter

Newsletter