Jameel Prize: artists inspired by Islamic tradition explore alternative narratives

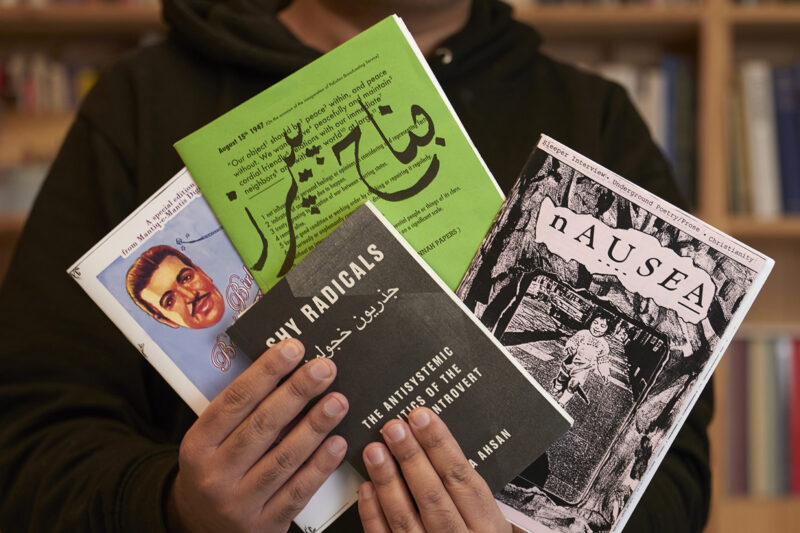

The V&A’s Moving Images showcases prize winner Khandakar Ohida and six other shortlisted contemporary artists from across the Middle East and South Asia

Since 1973, Khandakar Selim, a retired doctor’s assistant from the village of Kelebala in the Indian state of West Bengal, has been collecting quotidian items — perfume bottles, postage stamps, clocks, ceramics — amassing more than 12,000 objects over the past 50 years. Some things were given to him by patients he met during home visits in Kolkata, where he worked before his retirement. Others were acquired at second-hand markets.

Selim’s collection, previously housed in a now-demolished traditional mud home in Kelebala, is the subject of his niece Khandakar Ohida’s film Dream Your Museum (2022), the recipient of the 2024 Jameel Prize for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition. The film is presented alongside a selection of Selim’s objects at the V&A’s exhibition, Moving Images, devoted to showcasing the work of the seven artists shortlisted for the triennial award and on display until 16 March.

“In India, it’s always considered that you are collecting scraps or some sort of garbage,” Ohida says, explaining that Selim’s memorabilia and desire to build a museum to display the items was often ridiculed. In 2012, when Ohida herself planned to commence her studies at art school, Selim was instrumental in convincing the family that she be permitted to attend.

Dream Your Museum, and the accompanying display of commonplace objects — a Diwali card from a Central Bank of India manager, a bottle of Tom Ford’s Neroli Portofino eau de parfum, binoculars, pens — is a rejoinder of sorts to the formal, exclusionary narratives in museums with colonial origins in India, in which the histories of minority communities are often absent. Museums themselves remain a cultural space inaccessible to rural Indians, Ohida explains.

Instead, Ohida’s practice imbues what some might see as trivial detritus with elements of the fantastical, rooted in an understanding of the display as being part of a jadu ghar, or magic house, the Bengali term for museum. “In the village, all the children are more fascinated by the idea of a magic house,” Ohida says. “The word ‘museum’ is not a colloquial Bengali word.”

This resonates across the work of the other artists on display, whose audiovisual, photographic, and sculptural installations form part of Moving Images. Iranian artists Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian’s film, If I Had Two Paths I Would Choose the Third (2020), for instance, draws on iconoclastic imagery depicting the toppling of political statues in the Middle East, overlaid with images of mystical creatures from the 13th-century cosmographic text Aja’ib al-Makhluqat (The Wonders of Creation).

“I was excited by the opportunity to curate seven little solo shows, with each one offering an intimate and immersive encounter to a visitor,” says Rachel Dedman, Jameel curator of contemporary art from the Middle East at the V&A. “It’s less a group show than a kind of presentation of these amazing artists.”

Dedman was struck by the ways in which each artist engaged with multi-generational histories, drawing on ritual and local tradition in order to, in some cases, speak to broader concerns about landscapes and environment. Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican artist Alia Farid’s Zamzamiya, a sculpture placed at the entrance of the exhibition, is inspired by the traditional sabeel — public water fountains commissioned by individuals for their community. As desalination plants replace rivers as a primary source of water in Iraq, where Farid shot two films also on display, the sabeel, Dedman suggests, represent “talismans of the petrochemical age”.

Meanwhile, Zahra Malkani’s Darya, Darpan (River, Mirror) and A Ubiquitous Wetness, a set of field recordings and a soundscape combining chants, conversations, laments, and fisherfolk songs in Urdu and Sindhi form part of an audio archive of communities living along the Indus River in Sindh, Pakistan. Some of these were recorded, partly, in the aftermath of devastating floods in 2022, and in the face of ongoing extractivist development projects that threaten the environmental practices of the coastal communities that have cared for the river over centuries.

“The river is central to Sindhi culture,” Malkani says. “I’ve become increasingly aware of how strong and vibrant and long-lived the tradition of ecological defense in Pakistan is, and especially in these aquatic landscapes, how much that tradition is in continuum with our really syncretic and expansive devotional worlds.”

Elsewhere, the changing nature of spiritual practices is a focus. Iranian-Iraqi artist Marrim Akashi Sani’s photo series considers the ways in which the holy month of Muharram is observed by her community in Detroit, Michigan, and how rituals and religious expression are acquiring a uniquely North American hue. One photograph depicts how Barbie dolls and mass-produced key chains bearing the likeness of Imam Hussain are included as part of offerings in the name of martyrs. Another, highlighting the ways in which post-9/11 surveillance has contributed to heightened degrees of paranoia within American Muslim communities, shows a mantelpiece decorated with banners dedicated to Imam Hussain, above which a flat-screen television is placed, displaying a feed from several security cameras around the exterior of the home.

Animation and 3D simulation provide a means to explore elements of family lore. Iraqi artist Sadik Kwaish Alfraji’s hand-drawn animations centre his parents, Wabriah Shayal and Abdulhussain Kwaish. Shayal’s hand is the focus of A Thread of Light Between My Mother’s Fingers and Heaven, drawn from his memories of her making bread on a tannour, while A Short Story in the Eyes of Hope uses photographs of Kwaish overlaid with a recording from the burial prayers at his funeral in Najaf — a moment of mourning that Alfraji, now based in the Netherlands, could not attend.

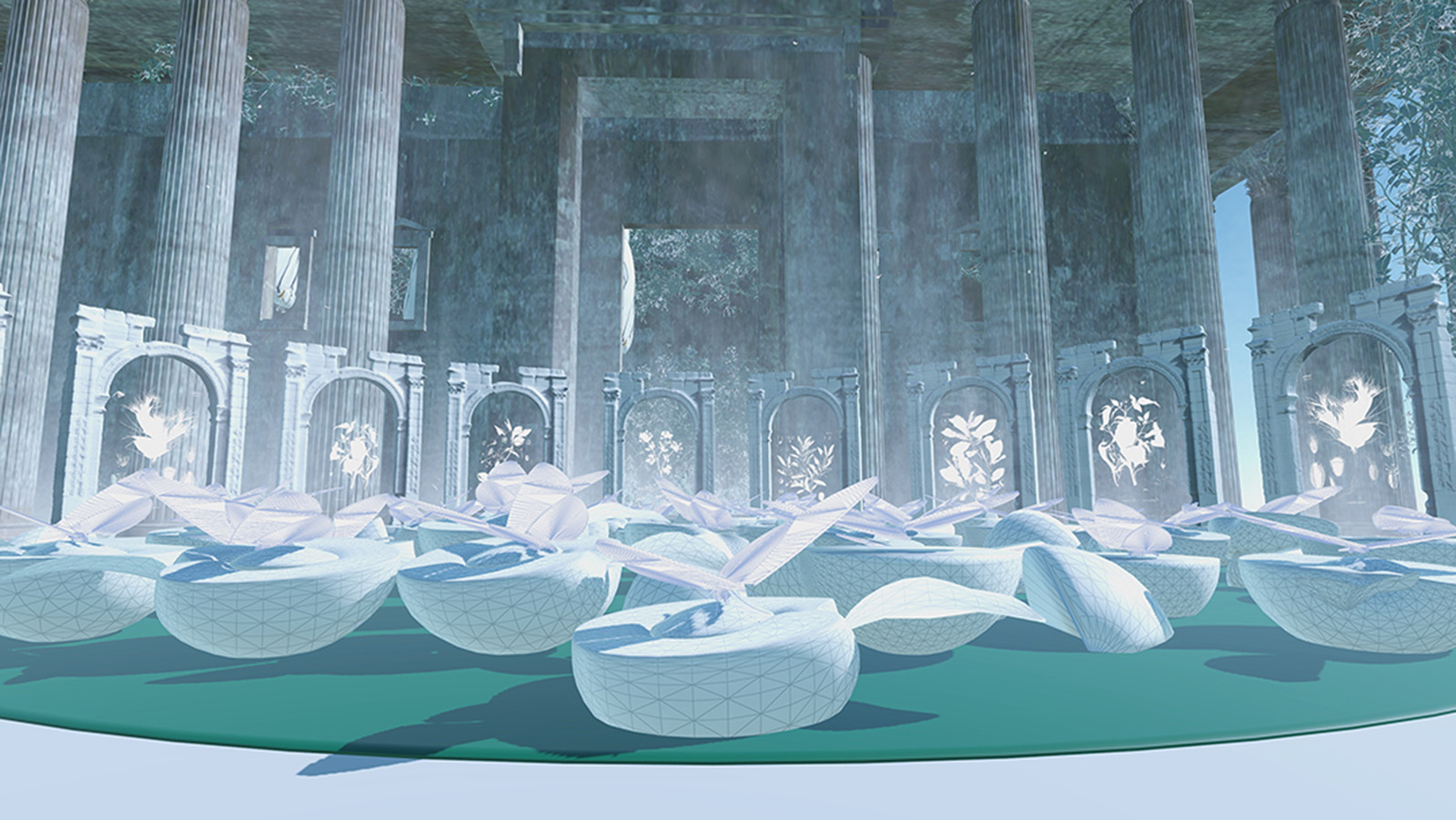

The ruins of Palmyra are reconstructed in the 3D virtual world of Syrian artist Jawa El Khash, who visited the heritage site as a child in 2002. Much of the ancient city was destroyed during occupation by Islamic State. “I was drawn to digital world-building as I felt it offered me the freedom to create whatever my mind imagines,” El Khash explains. “I wanted to translate the feeling of scale that I experienced when I was a child.” The simulation is designed so that viewers are immersed in the ruins from the vantage point and size of an ant, befitting the immense scale of the original site. Inspired by her grandfather, a doctor of plant pathology, the simulation incorporates plant life that might have once been present in Palmyra. “It’s a resurrection of a memory,” El Khash says.

It is exactly this possibility — of alternative realities and memory-making — that echoes throughout the exhibition. At one point in Ohida’s film, a young girl, played by her niece, asks Selim about the white “Museceum” — mispronouncing the word — that she saw in a photograph, referring, presumably, to the Indian Museum in Kolkata, located beside the art school that Ohida attended. He explains that his museum is different, that it exists on the moon. “How would you go to the moon?” she asks. “You can go there in your dreams,” he tells her.

Jameel Prize: Moving Images is showing at the V&A until 16 March 2025.

Newsletter

Newsletter