Policy Exchange told the Tories that Muslims were a threat. Will it work on Labour?

The Westminster thinktank has played a crucial role in shaping narratives about Islam and extremism in Britain since 2005

In the aftermath of the Islamophobic riots that swept Britain this summer, a strange quiet descended on Old Queen Street in Westminster.

Policy Exchange, the influential right-wing thinktank headquartered among its Georgian terraces, can usually be counted on to provide hardline responses to outbreaks of crime. When politicians want to look tough on law and order, it’s there that they often turn for ideas.

Yet a report on policing published by the thinktank in September had little to say about the UK’s biggest outbreak of violent disorder since 2011. Its 120 pages were more concerned with clamping down on protests against Israel’s bombing of Gaza, which it said had put people off going to restaurants — protests that Policy Exchange’s political allies had sought to portray as “Islamist hate marches”.

Policy Exchange rarely misses a chance to call for a more hardline approach on crime, be it littering or antisocial behaviour. To understand why it was relatively unmoved by thousands of people unleashing a wave of racist violence, we should recall the way it has helped shape narratives about Islam in Britain over the last two decades.

Ask people outside Westminster whether they’ve heard of Policy Exchange, or like-minded groups such as the Henry Jackson Society or the Centre for Policy Studies, and most will look at you blankly. But, even if their names don’t ring a bell, you will have heard politicians and journalists rehearsing their ideas.

In simple terms, thinktanks carry out research and suggest policies for governments to consider. In practice, however, it can be hard to tell who is calling the shots: ministers, the thinktanks or their wealthy backers.

This is partly because of their cosy relationship with the media. Thinktank reports on issues as varied as knife crime and integration are a reliable source of stories and journalists readily use the staff of such organisations as expert sources, enabling them to influence public opinion.

“Often we think of the ideas as coming from the news media itself,” says Tom Mills, a senior lecturer in sociology and policy at Aston University in Birmingham. “But there are also these organisations that are responsible for providing the talking heads and also the talking points, which then formulate policy, which then influence what politicians say.”

For Policy Exchange, the politician was David Cameron and the moment was 2005. Cameron had launched his campaign for the Tory leadership at the thinktank’s HQ that year, a location that aligned with his pitch to “modernise” the party after three bruising election defeats. Policy Exchange had been founded in 2003 by a group of Tory MPs who believed the party should draw inspiration from Tony Blair to get back into government. Its first chair was Michael Gove, who would later serve as a minister in several Tory cabinets.

What Policy Exchange gave Cameron was a philosophy of counter-terrorism that echoed the clash of civilisations previously envisioned by Tory MP Enoch Powell, cloaking it in a new veneer of liberalism.

The London terror attacks on 7 July 2005, a few months before Cameron’s victory in the contest, marked a pronounced shift in Policy Exchange’s output. Previously, it had suggested that the roots of terrorism were varied and often related to political or economic grievances. But from 2005 onwards, it began to link terrorism to immigration, multiculturalism and Islam.

The philosophy that Policy Exchange now espoused, says Arun Kundnani, the author of three books about racism and Islamophobia, was that Muslims had failed to integrate into British society because they had held on too tightly to their own cultural values. For Policy Exchange, this was no longer just an issue of integration, but one of national security. This separatism was supposedly creating the social and cultural basis for the kind of extremism that leads to terrorism.

As Cameron waited out the five years between elections, Policy Exchange developed this theory. Its 2007 report Living Apart Together — co-authored by Munira Mirza, who would later serve as a policy adviser to Boris Johnson — claimed that efforts to combat discrimination were doing more harm than good. “The preoccupation with monitoring racism seems to coincide with increased racial tensions between groups,” it said, adding that Britain should be far more concerned by “Islamist sectarianism” and “anti-western ideas”.

The report coincided with a speech in which Cameron attacked multiculturalism and said Muslims who “demand special treatment for their faith” were “the mirror image” of the British National Party. Cameron singled out the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), claiming — in an echo of a past Policy Exchange report — that it had been taken over by “hardliners”. The MCB responded that it had “never lobbied for special rights and privileges, only for parity in the application of the law and equal respect” and that it had “been unremitting in its active condemnation of extremism”.

For Policy Exchange, hitching its wagon to Cameron had paid off. Several news reports covered its research alongside the speech, and a Tory shadow minister described it as the “leading thinktank on Islam and Muslim-related matters”.

As the thinktank’s influence grew, so did questions about the integrity of its research. Later that year, Policy Exchange published a report claiming that “radical material” was being distributed in a quarter of Britain’s mosques. This was proof, it said, of the very Muslim separatism that Cameron had criticised. But when Policy Exchange tried to pitch its findings to BBC Newsnight for a story, journalists there found evidence that it had fabricated some of its findings.

Undeterred, Policy Exchange — which never directly addressed Newsnight’s allegations — proposed a full-blown policy response to the problem it had seemingly invented. The thinktank set out a fundamental shift in counter-terrorism policy less than a year later in a pamphlet titled Choosing Our Friends Wisely. The government, it said, should broaden its focus from preventing violent extremism to countering “non-violent radicals” who were “indoctrinating young people with an ideology of hostility to western values”.

Hyphen contacted the authors of the reports as well as current staff members asking for an interview, but none replied.

Mills, whose research at Aston University has focused on counter-terrorism, said the thinktank was reframing political violence as a cultural problem to justify an authoritarian set of solutions waiting in the wings.

“Whereas most people, on the face of it, would understand various kinds of terrorist attacks as being related to particular types of geopolitical conflicts in the world, the argument that was being made by some of these thinktanks was that, really, what we’re looking at here is something like the war of ideas — a set of people who don’t understand or don’t subscribe to western values versus those who do,” he said.

To tackle non-violent extremism, the Choosing Our Friends Wisely report called for the government to engage in political counter-subversion. This controversial strategy, which involves monitoring and infiltrating civilian political groups, was used during the cold war on the grounds that it would protect national security. In practice, trade unionists, peace activists and socialists critical of the government became its targets.

The report’s authors said it was “remarkable” that the security services no longer pursued such tactics and suggested reviving them to target “Islamists”. “We should ask whether the intelligence services need to recover some of their intellectual inheritance in relation to developing a definition of subversion fit for the challenges of the twenty-first century,” they wrote.

The language that had during the cold war stoked alarm over a fifth column of communists threatening the nation was now being used to recast Muslims as an internal threat.

When Cameron became prime minister in 2010, he brought Policy Exchange’s ideas into Downing Street.

In a speech given a year later at the 47th Munich Security Conference, he declared that multiculturalism had failed. It had “encouraged different cultures to live separate lives” and “much more active, muscular liberalism” was needed to combat it. Months later, the government published a new version of its counter-terrorism strategy, Prevent. The rewritten version reflected many of the talking points that Policy Exchange had set out two years previously.

Prevent would, from now on, tackle non-violent extremism, which the government defined loosely as views that were against “British values”. It would no longer involve programmes aimed at addressing socio-economic inequalities. Instead, new legal duties were imposed on schools to actively monitor individuals at risk of radicalisation. In 2015, these would be extended to local councils, prison services, youth groups, universities, police forces and even the NHS.

The change led to a flood of referrals. In 2014, the Home Office said that 484 people had been referred to its Channel counter-extremism programme, a precursor to Prevent. But in the year after the Prevent policy was expanded, the number of referrals jumped to 7,631. More than half were 20 or younger.

Kundani says the impact was to institutionalise Islamophobia. “If you have a policy like Prevent where you are training hundreds of thousands of public sector workers in supposedly spotting the signs of extremism amongst young Muslims, which is what was going on back then, you are creating a kind of culture of Islamophobia in public institutions,” he explains.

It worked. By 2017, according to Conservative peer and former minister Sayeeda Warsi, a covert form of bigotry towards Muslims “couched in intellectual arguments and espoused by thinktanks, commentators and even politicians” had become socially respectable. That year, the number of reported anti-Muslim attacks and incidents of abuse hit their highest since the group Tell Mama began monitoring such incidents in 2011.

Muslim charities warned in 2018 that work to combat this discrimination was being hindered, in part, because the government had no agreed definition of Islamophobia. With Cameron no longer in office, Tory communities secretary James Brokenshire rejected the first stab at a definition made by an all-party parliamentary group (APPG) of MPs but said he backed the idea in principle.

Policy Exchange was less keen on these efforts. In a written submission to a parliamentary inquiry on defining Islamophobia in January 2019, the thinktank criticised not only the proposed definition as an infringement on free speech, but also the word “Islamophobia” itself as stifling debate within Muslim communities.

It got its way. When Boris Johnson became prime minister in July 2019 and appointed former Policy Exchange chair Gove as Brokenshire’s replacement, efforts to define Islamophobia stopped. Gove reportedly felt that the definition proposed by MPs was “drivel” and, in January 2024, the government confirmed it would not be adopting a definition of Islamophobia, citing free speech concerns just as Policy Exchange had done. Instead, it would use the term favoured by the thinktank: “anti-Muslim hatred”.

But Narzanin Massoumi, who has written books on Islamophobia and lectures in sociology and criminology at Exeter University, says this wording is inadequate because it “doesn’t capture the systemic nature of racism” that Muslims face.

“Those that are resisting the recognition of that term are doing so because they perceive it as a threat to their own ability to have a licence to be racist, effectively, a licence to say Islamophobic things,” she said.

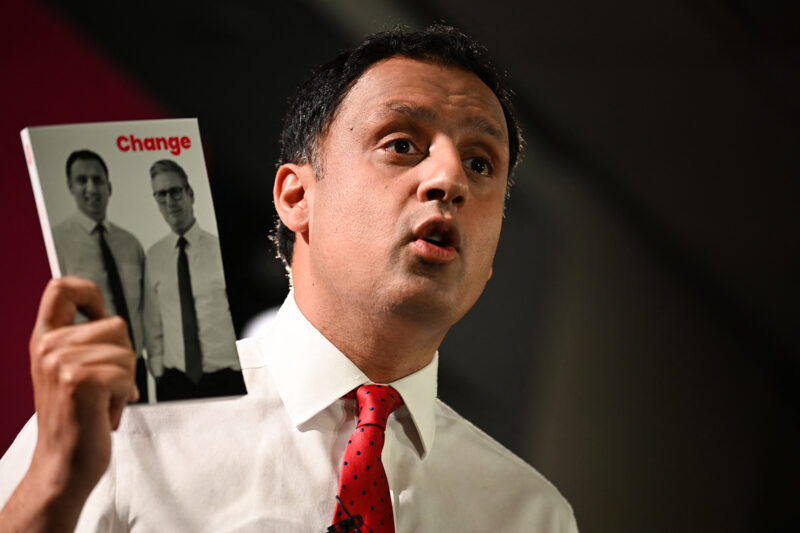

Labour’s routing of the Tories in July’s general election left thinktanks such as Policy Exchange — which had for 14 years enjoyed unfettered access to ministers — scrambling to make inroads with a new government.

Two months after Keir Starmer entered Downing Street, Policy Exchange launched a Future of the Left project, spearheaded by Labour peer Maurice Glasman — a founder of the socially conservative Blue Labour pressure group — and former Labour MP and 2015 manifesto chief Jon Cruddas, who retired from parliament this year. Glasman said at its launch event that the project would seek to create an agenda to “shape not just the future of this government but of our party”.

A key test for such efforts will be whether Labour’s position on Islamophobia shifts. The party backed the original APPG definition while in opposition. Labour MP Wes Streeting — who was co-chair of the APPG when it drew up the definition — is now health secretary.

Yet a written answer on the subject from junior communities minister Alex Norris in September appeared to suggest the new government was quietly backing away from the definition, just as the Tories had done. When Hyphen asked Norris’s department to clarify its position, it declined.

Meanwhile, Labour ministers have embraced Policy Exchange even as recognition has grown of the harmful impact its influence has had on Muslim communities. In February, while in opposition, the now defence minister John Healey praised the “pulling power” and “persistence” of the thinktank’s director Dean Godson during a speech on defence policy at its HQ.

Streeting was even more forthright at an event organised by the thinktank to discuss the NHS in 2023. “God loves repentant sinners,” he said, when Policy Exchange’s Conservative roots were pointed out.

Mish Rahman, a former member of Labour’s National Executive Committee and a prominent Muslim voice within the party, fears all this could spell bad news.

“In terms of Islamophobia, if the Labour party continues to work with the likes of Policy Exchange, it’s going to be very, very similar to the Tories,” he said.

“My fear is that instead of fostering social cohesion, fighting systemic racism, promoting equality, Labour will be doing the opposite.”

Newsletter

Newsletter