South Asians have a long history as part of the British working class

A rich heritage of grassroots activism and organisation should be embraced and celebrated

A few days ago, I visited Wilmslow Road in Manchester. Known affectionately as the Curry Mile, this vibrant street has been a hub of South Asian life since the 1950s, when workers from the nearby mills and factories used it as a meeting place to grab a bite to eat after their shifts. Today, one in five Mancunians are of Asian heritage — a total of 115,000 people.

Across the UK, South Asians number around 5 million people. Curry Mile equivalents exist in numerous towns, from Bury Park in Luton to Birmingham’s Ladypool Road. Behind their colourful storefronts lies a decades-long story of immigrants who arrived in the UK seeking economic stability, then built their own thriving working-class communities. That history, however, is seldom discussed and rarely celebrated.

I was in the north-west to deliver a talk at the Manchester Industrial Relations Society on British South Asian trade unionism, highlighting the community’s legacy of fighting back against discrimination by both employers and the unions that were supposed to protect them.

That struggle goes back hundreds of years. At its height, the British Empire covered a quarter of the globe. Its colonies were home to 400 million people and India was the jewel in its crown. As early as the 17th century, South Asians from Bengal, Gujarat and other coastal regions were recruited by British merchant shipping companies to transport spices, silk, tea and textiles around the world.

Known as “lascars”, those seamen were paid a fraction of their white counterparts’ wages and faced gruelling workloads and appalling living conditions. Many were mistreated. Joseph Salter, a Christian missionary who supported lascars abandoned in British port cities during the 19th century, documented their stories of torture and abuse.

In the century-long period encompassing the Napoleonic and first world wars, the number of South Asian seafarers on British merchant ships increased significantly. Many went on to settle in major port cities, from east London to Cardiff.

Their earliest attempts to collectivise came in 1917, when the communist MP Shapurji Saklatvala launched the Workers’ Welfare League (WWL). The group’s work was closely monitored by the authorities after recruitment drives in Liverpool, London, Cardiff and Glasgow. While those efforts were largely unsuccessful, the WWL was one of the first organisations to emphasise the importance of forging links between South Asian and British workers.

In 1919, however, the Trades Union Congress condemned the use of “Asiatic labour” in the shipping industry following racist rioting by white seamen in Glasgow. That pattern of hostility to Black and Asian workers persisted for many years within the British labour movement.

As a result, South Asians had to form their own organisations, including the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA), set up in 1939 by Punjabi street traders in Coventry. Many of those involved had been members of communist parties on the Indian subcontinent and had a well-developed sense of themselves as part of an international working class.

In the years following the second world war, tens of thousands more South Asian workers moved to Britain to fill labour shortages. New communities sprang up around the factories, mills and foundries they staffed. Pay was low, hours were long, conditions were grim, and their reception by white colleagues and neighbours was often less than welcoming.

Many were men who had left wives and children at home. Thousands of miles from their families and often isolated from the communities around them, they began to forge a collective identity as a discrete but vital part of the British working class, joining organisations such as the IWA and trades unions in their respective industries.

Some of the earliest industrial action involving South Asian workers took place at the R Woolf rubber factory in Southall, west London. In 1963, IWA members recruited extensively for the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU). Their efforts led to union recognition and an end to the practice of white supervisors demanding bribes from South Asian workers in return for shifts.

In 1964, they secured the reinstatement of one of their members for insubordination via strike action. A subsequent seven-week walkout in 1965 over the dismissal of 10 union members for their organising efforts failed, owing to a lack of official support from the TGWU. Denied strike pay, the 600 workers involved were instead forced to rely on the help of the IWA and the wider community.

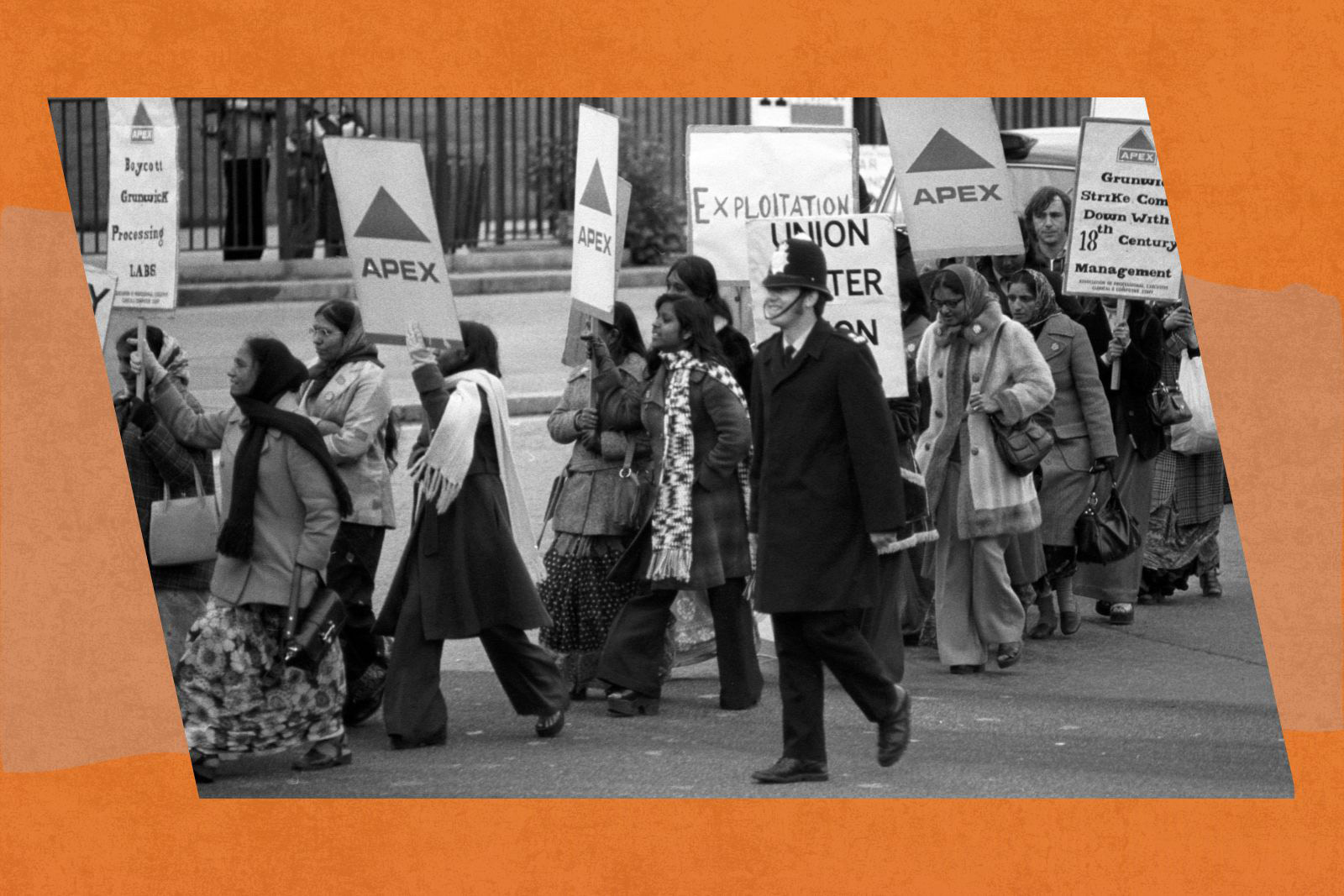

Similar stories played out across the country. Following the arrival of thousands of South Asians from east Africa in the 1970s, women from the community led industrial action against discriminatory workplace practices at Mansfield Hosiery in Loughborough in 1972, Imperial Typewriters in Leicester in 1974 and the London-based Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories in 1976. Many union activists also supported disputes involving predominantly white workers, including joining picket lines and fundraising efforts during the 1984 miners’ strike.

Today, the majority of South Asians remain low-wage earners. According to the Child Poverty Action Group, 67% of Bangladeshi children and 58% of Pakistani children live in poverty. A recent study by the Fawcett Society also found that women of Bangladeshi and Pakistani heritage in the UK earn almost one-third less per hour than white British men. And yet there now appears to be a reluctance among many to identify as working class and a prevailing idea that such an identity is something to be risen above, rather than proudly embraced.

South Asians are also often erased from wider conversations about class. We hear a great deal about the white working-class but much less about minority communities that have also been affected by deindustrialisation, cuts to public services and the erosion of social infrastructure. To me, a narrative that obscures the intersection between race and class and the importance of solidarity, both within and beyond our own specific communities, is a narrative that only empowers those who wish to divide and exploit us.

Recently, I took a guided tour of East India Docks in London. The road names — Clove Crescent, Coriander Avenue, Saffron Avenue — all refer to the spoils of empire. Hundreds of years ago, while colonial powers prospered, lascar seamen lived in squalid conditions on those streets. Today, Tower Hamlets is home to the UK’s largest Bangladeshi community and one of the poorest boroughs in the capital. There, in the shadow of Canary Wharf and the towers of the financial district, I couldn’t help thinking how little has changed and how much work there remains to do.

Newsletter

Newsletter