The Great Mughals: landmark exhibition celebrates the staggering variety of an artistic dynasty

The V&A’s showcase carefully curates the opulent art, manuscripts and fine objects spanning the golden age of the Mughal empire

In the summer of 1982, a series of exhibitions organised under the auspices of the Arts Council were held in London as part of a “festival of India”. “London feasts on an array of treasures,” the New York Times declared. The Economist characterised the works on display as belonging to an ancient civilisation “whose high art rivals that of China and Greece”.

One of the major museum shows that year was the V&A’s exhibition on arts under Mughal rule curated by Robert Skelton, who amassed some 500 objects — among them paintings, carpets and decorative arts. At the time, it was one of the most comprehensive surveys ever held of Mughal art.

Now, with the V&A’s The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture, and Opulence, open until May 2025, the variety is equally staggering. Curator Susan Stronge hones in on artistic production during the reigns of emperors Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan, to offer a more engaged portrait of courtly art and culture between 1580 and 1650.

Founded in 1526 following the invasion of the Delhi sultanate by Akbar’s grandfather Babur — a descendant of Amir Timur and Genghis Khan — the Mughal empire came to encompass an area covering much of the subcontinent, including parts of contemporary Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

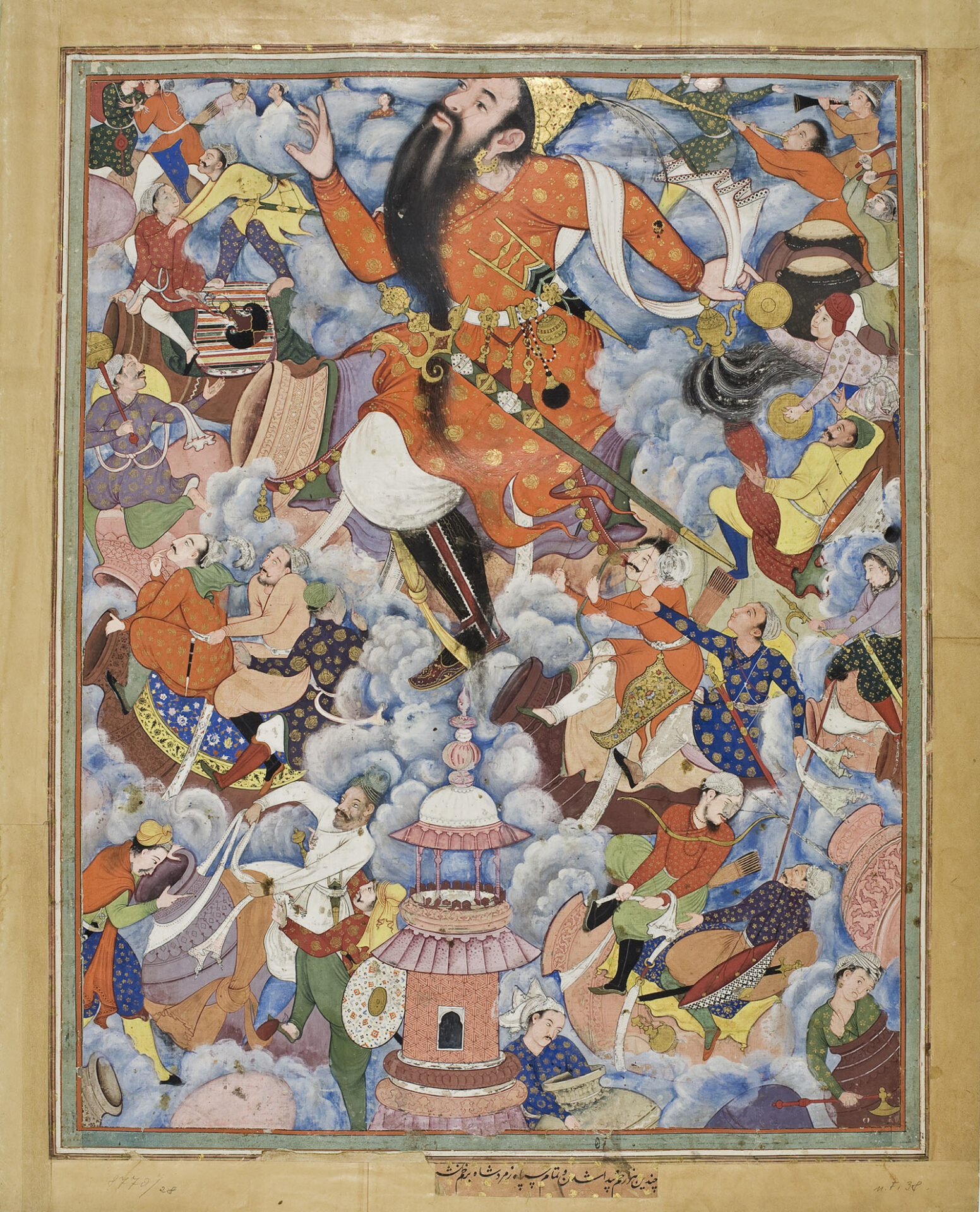

The golden age of Mughal art, the exhibition suggests, fell during the 70-year-period under examination by the V&A, during which highly skilled Hindu and Muslim artists and craftsmen were employed in workshops that received royal patronage.

First conceived in 2018 and three years in the making after planning was halted by Covid-19, the V&A presents 221 pieces, from illustrated manuscripts to textiles and fine objects. On loan from the al-Sabah collection in Kuwait is a 249-carat spinel gemstone sent by Shah Abbas of Iran — known as Abbas the Great — to Jahangir in 1621 and later fitted into Shah Jahan’s throne. Diamonds mined in the sultanate of Golconda in southern India flank the spinel. The lollipop shape and size of the gemstones go some way to help envisage the wealth of the Mughal rulers. Sir Thomas Roe, the first English ambassador to the Mughal court, wrote in a letter home that Jahangir’s empire was “the treasury of the world”.

Some of the most striking items on display are often those that served a utilitarian purpose. “I wanted to emphasise the fact that in Mughal art, as in most eastern art, you don’t have the western divide of fine and decorative art and the kind of hierarchy that implies,” Stronge says. They include inlaid wooden cabinets produced in Gujarat and decorated in mother-of-pearl. A silver casket for a miniature Qur’an covered in engraved plants, animals and Arabic inscriptions offers one of the earliest examples of Mughal enamelling, while a cornucopia of tigers, elephants and deer is carved on an ivory priming flask, which was used to load guns.

Elsewhere, folios and objects reflect the multicultural nature of the Mughals. “I think it’s a particularly British problem to divide everyone into groups,” Stronge says, referring to how Hindu notables at court and Muslim elites were all immersed in a shared Persianate culture. Akbar, famously, was a proponent of the Din-i Ilahi, a syncretic faith combining elements of Sufism and Hinduism. One manuscript painting produced in a Mughal workshop in Lahore and originally owned by Akbar’s mother, depicts a story from the epic Ramayana, in which the Hindu goddess Sita shies away from Hanuman. A divination ring and a set of 12 gold mohurs (coins) bearing the signs of the zodiac, underscore an interest in spiritualism and the practice of astrology.

Surveys such as this are an opportunity to see disparate objects, which were removed from their original context by piecemeal acquisitions often undertaken during the colonial period, reunited. Here, two folios from a volume commissioned by Akbar are on display, rarely presented together.

Interspersed throughout the exhibition is a growing awareness and interest in the arts imported by Europeans, beginning with Akbar and Jahangir’s close study of prints and engravings brought by Jesuit missionaries and incorporated into works by court artists, including adaptations of biblical narratives.

By Shah Jahan’s reign, during which the Taj Mahal was built, the overt cosmopolitanism of the court was at its zenith. One painting described as a “princely gathering in a garden” depicts several luxury items, including an Iranian ceramic flask to pour wine, a Venetian glass decanter and goblet, Chinese porcelain cups and brocaded satin, referencing the diversity of those who came to the Mughal court. In another work, European traders are shown holding a box seemingly made of Japanese black lacquer, while presenting the court with what appears to be a Colombian emerald.

As one exits the exhibition, a row of fragments from glazed earthenware tiles are displayed on a wall, created using a technique known as cuerda seca, through which the application of a viscous line helps to ensure that colours do not mix. These tile revetments adorned palaces, mosques, and gateways.

Above the tiles, an inscription from the 13th-century Sufi poet Amir Khusrow speaks not only to the decadence that defined the artistic tastes of a wealthy court. But also, perhaps, to the moment of religious and cultural pluralism that was cultivated by the three Mughal rulers featured here, long before European colonisation and the divisions it wrought and solidified. The inscription reads: “If there is paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this.”

The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence is showing at the V&A South Kensington until 4 May 2025.

Newsletter

Newsletter