In focus: the roots of Cardiff’s thriving Somali community

In a new series, Hyphen visits the cities, towns and neighbourhoods across the country that British Muslims call home

Nestled within the historic docklands of Cardiff lies Butetown. Also known as Tiger Bay, this compact neighbourhood is home to one of the largest and oldest Somali communities in the UK.

Walking down the main road of Bute Street, the first thing I notice is that one side is walled off, with a train line running directly behind it, separating the area from the rest of the city. Opposite, shops catering to multicultural residents line the road, including a halal butcher and a convenience shop selling abayas, prayer mats and bakhoor, alongside an array of everyday groceries.

It quickly becomes apparent that this is a place where everyone knows each other. A driver honks their car horn to get the attention of a friend on the pavement, older men greet each other at the bus stop and others congregate outside the Togayo Cafe, a small diner that has been a gathering spot for local Somali men for more than 25 years.

The roots of Cardiff’s present-day Somali community are firmly planted in the city’s maritime past. In 1869, the opening of the Suez Canal transformed global trade and sparked a boom in Britain’s ports. By the late 19th century, demand for skilled sailors brought the first east African and Yemeni settlers to the Welsh capital. Hundreds of men journeyed to the city, working on merchant ships as deckhands and stokers, transporting coal throughout the British empire and beyond.

“The first Somalis came in 1894, so we’ve been here for a very long time,” says Nasir Isa, a longtime Butetown resident. “Somalis came here in the heyday of Cardiff when it was like Dubai or Saudi Arabia — everybody used to come, especially to Tiger Bay, because it was so multicultural. The nearby Masjid Noor El-Islam is the first purpose-built mosque in Wales, established by Somali and Yemeni seamen in 1947.”

During the late 1980s and 1990s, the Somali community grew as people fleeing the country’s civil war came to Cardiff. While the original seafaring founders had mostly been men — some of whom married local women, while others travelled back and forth to visit families in Somalia — many of the new arrivals were women and children. Now, according to the 2021 census, around 10,000 people in the city identify as Somali.

During his time in Cardiff, Isa has seen even more changes. Arriving in the UK in 2001, he based himself in London initially, but decided to make his home in Butetown where he had family.

“When I first came here, the community was made up of mostly older seamen who arrived between the 1950s and 1970s. Most of them have passed away now,” says Isa. “Now there are more than 20 mosques and almost 40,000 Muslims in Cardiff. The community has grown rapidly.”

Now, alongside his day job as a taxi driver, Isa runs the Butetown-based charity Somaliland Mental Health Support Organisation. Founded in 2011, the group focuses on mental illness experienced by survivors of the years of conflict in Somalia. In the beginning, Isa and his team concentrated on helping people in east Africa, including raising funds for the construction and refurbishment of hospital psychiatric wards. Now, the organisation has shifted focus to also provide help within the local community. Isa hopes that work will continue for generations to come.

“We’re a group of seven middle-aged men, so we don’t have the manpower to run everything as we’d like,” he says. “We want more of our youth to work with us and to understand the importance of charity. We want the younger generations to learn the ropes and take over. We don’t want to keep this charity with ourselves.”

The more I see of Butetown and the more of its residents I meet, the less I think Isa has to worry about. Many younger Welsh Somalis, born and raised in Cardiff, are already trying to make a difference. From the Hayaat Women Trust, a local education initiative supporting ethnic minority women, to the grassroots charity Foundation 4 Sport, there is a strong sense of dedication to the health and wellbeing of residents that spans all age groups.

As I enter the office of Foundation 4 Sport just off Bute Street, the room is filled with laughter and enthusiastic voices. One is that of Ahmed Noor, manager of the Cardiff Bay Warriors. Established in 2005 and playing at nearby Canal Park, this community-led football team has become a source of pride and unity for the Welsh Somalis.

“Being part of the team is more than just football,” says Noor, a former player who joined the Warriors at 14. After 30 years of playing, he took over management duties in 2019.

“It’s about discipline and community. This team is huge for us. If we have a big game, the stadium will be packed and we’ll have the games streamed live on YouTube. The community is always really proud of the boys.”

In 2022, the Warriors won the Somali British Champions League Final. In August 2024, they brought home from Toronto the Somali Week Cup, the trophy from an international tournament that brings diasporic Somali teams together from around the world.

“For some of the guys, going to Toronto was their first time travelling out of the country, so it was huge for them and our victory was big news for everyone here,” says Noor.

Noor’s father was a seaman who came to Butetown in the 1970s, where Noor grew up with his 10 siblings. Despite having moved out of the neighbourhood a year and a half ago, he still finds himself back most days.

“Butetown is one big melting pot and that’s all thanks to the people who arrived at the docks 70 years ago,” says Noor. “During the first world war, men from Somaliland came over to fight in the war and some of our seamen also fought in the Falklands war. A lot of people don’t know our history and don’t realise how much of it is enshrined in Cardiff.”

While most of my conversations with locals are positive, with many expressing a deep love for Cardiff and its people, some underlying issues of belonging and fears for the future of the community do creep through. For instance, when asked if he feels Welsh, Isa laughs and diplomatically describes himself as a “British Muslim”.

Yunus Mohamed, 27, one of the co-founders of Foundation 4 Sport, worries about the rapid gentrification that Cardiff is experiencing. Walking through the area he grew up in, he points out some building work taking place — particularly the site of the old Paddle Steamer Cafe, where he and his friends would go watch football and play snooker. It has now been knocked down and is being replaced by a new block of flats.

“We’re seeing more housing developments in the area, which are going to attract more corporate types to come live here,” says Mohamed. “It’s a real shame that all of this is happening within our community. We don’t have as many hubs or spaces any more where young people and adults can come together.”

Still, Butetown has an undeniable buzz about it, partly thanks to a growing number of young creatives and community workers using sport, art and fashion to tell their stories and express their dual Welsh and Somali identities. Of particular interest to me, as a journalist, were Docks, a magazine launched in 2020 that shines a light on community life in Butetown, and Al Naaem, an annual publication dedicated to celebrating Black and Muslim style and culture.

Asma Elmi, 26, the founder of Al Naaem, is passionate about providing a platform for Somali culture in Wales. Since 2022, she has worked with a group of young girls and women as part of the Young Queens Project with the Hayaat Women Trust to put on a fashion show with Somali folk dance and poetry.

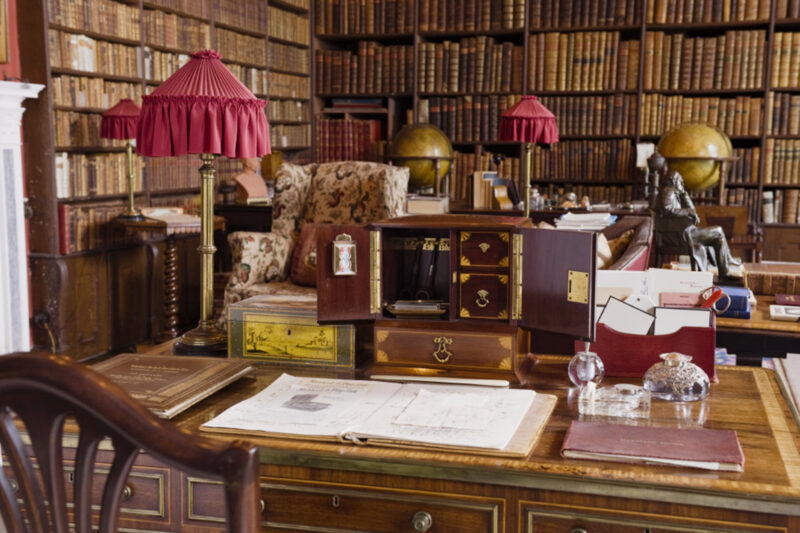

As part of the same project, she also organised an intergenerational arts project titled Faadi/Y Stafell Fyw/The Living Room which showcased Somali Welsh fashion and culture through photography. The exhibition has visited a number of prestigious venues, including Wales Millennium Centre and Ffotogallery in Cardiff and the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth.

“I was always very creative but didn’t have spaces like this to explore myself,” says Elmi. “My goal was to help these girls bring their ideas to life and their response made me more determined to create spaces for young creative Somali girls to represent their culture and heritage.”

As I wrap up my time there, it’s easy to see that a common thread runs through Somali Cardiff. From the intrepid seamen of the 19th century to the ambitious young people of today, each generation has played its part in shaping the city around them. And, just as Somali culture has found a place of its own in Wales, for most Wales has also become an important part of the Somali community’s identity.

“It took me a while to acknowledge my Welshness,” says Elmi. “But I can’t deny it, I grew up around the culture. I have a great culture and heritage back home, but this Welshness is always going to be a part of me.”

Newsletter

Newsletter