What a walking tour can teach us about Black Muslim history in Britain

From Westminster to the National Gallery, this guided tour reveals a side of British history that is often glossed over

On the corner of Caxton and Palmer streets in Westminster, central London, stands Caxton Hall — a tall, redbrick, 19th-century building that was once a town hall, and a key organising space for the suffragettes. A plaque by the entrance states that Winston Churchill once spoke here. But what it doesn’t mention is that the building is also believed to be where some of the earliest jummah prayers were held in London, in 1908.

Sudanese-Egyptian journalist, actor and activist Dusé Mohamed Ali is said to have organised jummah prayers at Caxton Hall after hearing from an imam at Woking mosque in Surrey who wanted to perform Friday prayers in central London.

“As you can see, he shares good taste in headwear,” our tour guide, AbdulMaalik Tailor, chuckles as he gestures from his own head to the photo he is holding of Ali wearing his trademark fez.

Born in Alexandria, Egypt in 1866, Ali was sent to study in the UK at the age of nine. His father and brother were killed in the 1881-1882 Urabi revolution — a nationalist uprising against British and French influence in the country. Following an unsuccessful search for his mother and sisters, who had been sent to safety in Sudan during the revolution, Ali returned to the UK, where he studied history at King’s College London. He later took up acting, where he was often given racially stereotyped roles such as the docile slave, or the “amorous sultan” in The Extreme Orient. Historian Ian Duffield believes it was his typecasting that made him acutely aware of the need to tackle the prejudices faced by people of colour, and Ali became known for speaking out against imperialism and racism. In 1912, he founded Britain’s first Black-owned and edited Fleet Street newspaper, the African Times and Orient Review, which reported on struggles against racism and colonialism around the world.

Our tour guide leads us around the corner to the London office of the Falkland Islands’ government. Tailor explains that British history lessons often omit stories of the Somali sailors who served in the Royal Navy in conflicts including the Falklands war in 1982. There are records of British Somalis dating back to the early 20th century where many Somali sailors and merchants travelled to Britain by ship and established communities in port cities such as Cardiff, Liverpool and London.

“People don’t know about this part of history,” Tailor tells us. “When I speak to people in the Somali community, I often find they haven’t heard about this.”

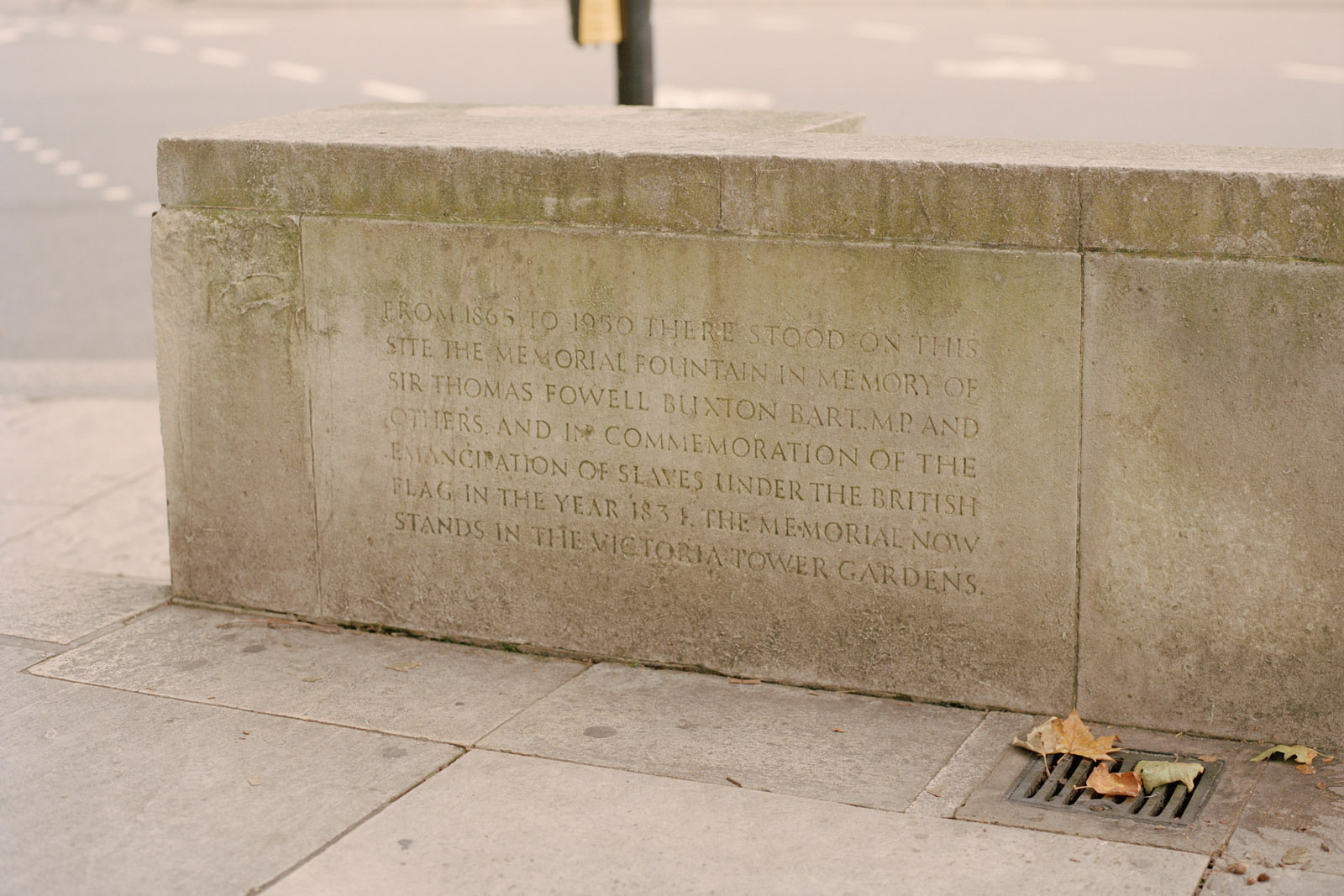

Dodging between crowds of tourists and workers on their breaks, we reach Parliament Square. “In this square, there is a plaque that gives some recognition to slavery. Where do you think it is?” Tailor asks. After a few wrong guesses, he leads us to a low stone wall in a corner of the square.

“From 1865 to 1950 there stood on this site the memorial fountain in memory of Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton Bart MP and others, and in commemoration of the emancipation of slaves under the British flag in the year 1834,” the inscription reads.

The Buxton memorial fountain was erected in dedication to British slavery abolitionists and removed in 1950 before being placed in Victoria Tower Gardens in 1957. As we walk to the gardens, Tailor laments the fact that a memorial was built to celebrate white, British politicians who campaigned for abolition, yet there is no such memorial in Parliament Square for the 12.5 million Africans who were stolen from their homes during the transatlantic slave trade — 3.4 million of whom were transported by British ships.

According to historians, 15 to 30% of Africans stolen from their homelands came from the Islamic regions of what are now known as Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Gambia. Many are believed to have continued practising their Islamic faith, passing on their cultural legacies to their descendants.

Our guide tells us that many slaves wrote about their experiences. Among them was Omar Ibn Said. Born and raised in Futa Toro, a desert region between present-day Mauritania and Senegal, Ibn Said was captured and taken to the US in 1807. In 1831, he wrote about his enslavement in Arabic.

“Then there came to our place a large army, who killed many men and took me, and brought me to the great sea,” an excerpt from his autobiography reads.

We soon find ourselves standing outside the Ministry of Defence (MoD) headquarters, partly constructed on the site of the Palace of Whitehall, where Henry VIII lived. But what do the Tudors have to do with Black history?

John Blanke was a trumpeter who worked for Henry VII and Henry VIII, and is believed to have come to Britain with Catherine of Aragon in 1501. He first appears in historical records in 1507. Little is known about Blanke’s early life, and while historians believe he was of African heritage, the records don’t reveal which country he came from. Many researchers doubt that Blanke was his birth name, believing it may have been a play on the word blanc, meaning white in French.

As we stand outside the MoD, Tailor holds up what is believed to be the oldest picture on record of a named Black person living in the UK. In the painting, Blanke and other trumpeters are on horseback sounding their trumpets during a jousting tournament held in 1511.

In portraits of Blanke, he is seen wearing a turban. Some historians say this may suggest an Islamic faith, but historians at the Historic Royal Palaces charity say Henry VIII liked to “dress himself, and members of his court, in a variety of international fashions”, so his headwear “may have been worn for aesthetic rather than religious reasons”.

Archival records show that Blanke received payment of 8d (old pence) a day as a royal trumpeter, but he argued that this wasn’t enough to live on. A petition, now held by the National Archives, shows that Blanke was successful in his campaign for an 8d increase to his wages.

Our last stop is the National Gallery, where a portrait of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo hangs. Diallo was born to a powerful family of Muslim clerics in the kingdom of Bundu, now known as Senegal. From a young age he studied the Qur’an and learned how to read and write Arabic.

In 1731 he was captured, taken into slavery and transported by the English-owned Royal African Company to the US. After a failed runaway attempt and several efforts to return home, Diallo’s captors agreed to send him to England where he learned English and impressed scholars by writing the Qur’an from memory.

He also sat for the earliest known British oil portrait of a freed slave in 1733 — which we’re now standing in front of nearly 300 years later. According to the National Gallery, when Diallo sat for his portrait he had some influence on how he was presented, telling the artist that he “wanted to be shown in his own country dress and wearing a Qur’an”, proudly identifying himself as a Muslim.

Diallo finally returned to his homeland as a free man in 1734. According to historians, despite his own experience as a slave, he went on to work for the Royal African Company to improve British trade positions against the French. He is believed to have been imprisoned by the French in 1737 and subsequently released.

As we wind up, we’re reminded of the overlooked histories of Black Muslims in Britain and the importance of telling their stories. For our guide, these tours are one step in the right direction. “You need to come out of the classrooms and on to the streets,” Tailor says.

The History of Black Muslims tour through London is led by Halal Tourism Britain and can be booked year-round.

Newsletter

Newsletter