What a year of war in Gaza means for the US election

For Muslim voters in America, Palestine is on the ballot. That could have some unexpected consequences

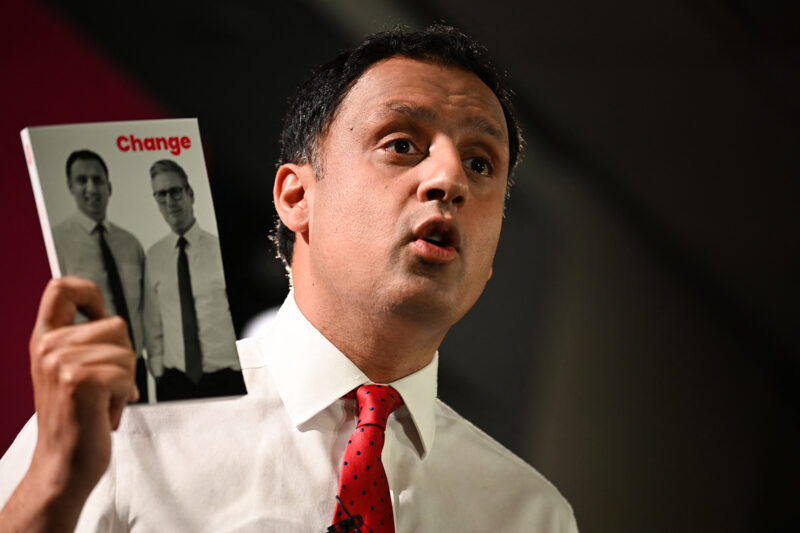

The invasion of Gaza made a firm mark on the UK’s general election in July, resulting in an unprecedented number of independent MPs — all of whom had voiced support for Palestine — unseating incumbents in parliament.

But while Gaza made waves during the primary phase of elections in the US this year, it remains uncertain how the war will affect the outcome on 5 November, when Americans vote for the next president.

A July opinion poll showed that a narrow majority of US voters disapproved of Israel’s actions in Gaza, though a more nuanced August poll found Republicans were more likely to say Israel’s actions were justified and Democrats more likely to say they weren’t. Either way, though, there is no indication that either of the major party candidates for president would put new restrictions on the US’s steadfast support for Israel.

Where do the main candidates stand on Gaza?

Support for Israel has been a constant feature of US foreign policy since the modern state was established in 1948. But during his first presidency, Donald Trump distinguished himself as a particularly strong ally to Israel and a close friend to its controversial prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. In 2017 Trump delighted Netanyahu’s government by recognising Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. He moved the US embassy to the contested city — despite the international community seeing the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem as illegal — and recognised Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights, land captured from Syria by Israel in 1967.

If he is re-elected, Trump says he will reinstate his 2017 travel ban on citizens of select Muslim-majority countries (which Joe Biden revoked at the start of his presidential term in 2021), and has specifically vowed to bar refugees from Gaza from entering the US. He has also denounced international students who voice pro-Palestianian sentiments on campus as “anti-American”, saying he will cancel their visas and impose “strong ideological screening” to prevent foreign nationals who “want to abolish Israel” from entering the US.

If elected, Democratic candidate Kamala Harris is expected to continue the ongoing cooperation with Israel, not straying far from Biden’s current policy. But Harris has taken a more compassionate tone concerning the overwhelming death toll of Israel’s assault on Gaza, and the humanitarian crisis that has unfolded over the past year.

In July, days after Biden ended his campaign and endorsed Harris as his effective replacement, Netanyahu addressed a special session of the US Congress. Harris did not attend. She instead met privately with Netanyahu a day later. In a press statement following the encounter, she spoke plainly about the bloodshed and humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza. “We cannot allow ourselves to become numb to the suffering and I will not be silent,” she said.

Harris’s track record also paints a picture of a politician slightly less loyal to Israel than Biden. During her time as a senator, she opposed a bill allowing local governments to cut off companies that engaged with the boycott, divest and sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel, and did not rule out “consequences” if Israel went ahead with its attack on Rafah in March – although none were then forthcoming when the attack happened. She had also called for a ceasefire earlier in March, ahead of Biden.

Lawmakers across both major political parties in the US support deep trade relations with Israel and routinely approve tens of billions of dollars in military aid for the country. The roots of these commitments run decades deep and have long been bolstered by an impressive flow of campaign donations and lobbying dollars from pro-Israeli groups. This year, 54 of America’s 100 sitting senators received donations from pro-Israeli groups. Since becoming a senator in 2016, Harris has received a little over half a million dollars from such groups. Although this is a significant sum, she has taken less than many of her counterparts. Mitch McConnell, the top ranking Republican senator, has accepted just shy of $2m.

What about pro-Palestine third-party candidates?

The most prominent pro-Palestine candidate in this election is the Green party’s Jill Stein. But voters who want their voices heard on this issue face a difficult choice. With Trump and Harris polling neck and neck in so-called “swing states”, any swing to the left, from the Democrats to Stein, could paradoxically benefit Trump — and potentially usher in an even more staunchly anti-Palestine policy regime than the current one.

In a two-party system like America’s, third-party candidates have slim chances of actually winning office — this has never happened at a national level. But they do allow voters to register their support for issues that those candidates campaign on. And in very close elections, they can contribute to tipping the balance. Some analysts have argued that Stein contributed to the Democratic defeat in 2016. Similar conclusions were drawn about Green party candidate Ralph Nader in 2000, when Republican George W Bush beat Democrat candidate Al Gore.

The country’s antiquated electoral system and a persistent 50-50 national divide between Democrats and Republicans means that outcomes of presidential elections typically ride on the decisions of voters who live in a small number of swing states — so-called as they often switch sides from one election to the next.

According to a September opinion poll carried out by the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), a Muslim civil rights and advocacy group, Harris and Stein are almost tied for support from Muslim voters at a national level, garnering 29.4% and 29.1% respectively. However, among Muslim voters in the swing states of Arizona, Michigan, and Wisconsin Stein enjoys a lead over Harris.

Some Democrat supporters are critical of progressive third-party voters, accusing them of handing the election to Trump. Others, though, feel they cannot in good conscience vote for a candidate who will continue to enable the bombing of Gaza.

Progressive voters who care about Gaza are in a bind, said Youssef Chouhoud, associate professor of political science at Virginia’s Christopher Newport University. “The Democratic nominee has not done anything to signal a policy shift regarding Israel, which is what these voters would like to see. But voting third party can make it that much easier for a Republican to get into office.”

For others, that might not be such a bad thing. “You’re really asking me whether I’m going to take a ban or a genocide? I’ll take a ban,” said Amer Zahr, a Palestinian American comedian speaking to the magazine Slate in April.

Are there other ways pro-Palestine voters can express their views?

More than 700,000 voters used the first phase of the election, known as the primaries, to signal their frustration with Democratic candidates and their stance on Gaza. These elections are normally used to determine who will be the nominee for each respective party, with the final decision made at their respective national conventions.

In the lead-up to the primaries, a protest group called the Uncommitted National Movement urged registered Democrats to cast a so-called “uncommitted” vote, rather than choosing any of the candidates on the ballot, to send a message to the party (and its then presumptive presidential candidate Biden) that their votes could not be taken for granted without a permanent ceasefire and an arms embargo on Israel.

While the “uncommitted” option garnered the highest support in Hawaii — where it received more than 29% of the votes — it was the 13.21% result in Michigan, a key swing state, that sent shockwaves through the Democratic establishment. The movement garnered enough popular support that it was able to send its own delegates to the Democratic National Convention.

It remains to be seen whether this current makes much of a difference in November. On the one hand, it is a Democratic movement, intended mainly to put pressure on the party from within, and its leaders have conceded that they would still rather have Harris in the White House than Trump.

“It’s important for us to have an eye toward not just the next week or two or the next month or two,” said Abbas Alawieh, one of the movement’s founders, in an interview with Jacobin, “but to the question of how we build an anti-war movement in our country that gets more power than the pro-war side.”

On the other, there is no real way of knowing whether the issue of Gaza could trump party loyalty for the “uncommitted” voters themselves. Some may well consider abandoning Harris or sitting the election out if they feel strongly enough that they cannot trust her on the issue.

What influence does the Muslim vote have in the US?

The Muslim population in the UK is proportionately larger than in the US, and is concentrated in a handful of constituencies where Muslims make up more than 30% of the population, meaning they can have a big influence on electing individual MPs.

The situation is different in the US, where Muslims make up approximately 1% of the population and are geographically dispersed. However, some large communities live in key states, especially Michigan, where they make up 2.4% of the population.

“If Arab and Muslim voters defected in large numbers to third party candidates, it would make it really difficult for the Democratic nominee to win in Michigan, Georgia or Arizona,” said Chouhoud. “These are large enough communities and small enough margins that those communities alone would be able to potentially tip the scales.”

Additionally, while in the UK Muslims have traditionally been loyal Labour voters, Muslim voting history and preferences in the US are more diverse. In the 2000 election, 78% of Muslims voted for Bush. While Republican support among Muslims fell dramatically following 9/11 and the subsequent increase of Islamophobia across the US, Chouhoud said he still expected to see a rise in support for Trump among socially conservative Muslims.

“That split in the community [between right and left wing voters] was growing wider up until 7 October,” Chouhoud said. “Gaza is one of the few issues – if not the only issue – that unites nearly all Muslim voters.”

According to CAIR, more than 2.5 million Muslims have registered to vote in this election, a significant increase from the 1.5 million registered to vote in 2020 and the little under a million estimated to have registered in 2016.

The increase in Muslim engagement with electoral politics is driven not only by the invasion of Gaza in 2023, but by years of campaign and mobilisation efforts by groups like CAIR, said Robert McCaw, government affairs department director at the organisation.

“It’s incredibly important in American politics to be organised, as best you can be, as a bloc to have your voice heard,” said McCaw. “Today, every Muslim house of worship – every masjid, every Islamic centre — is a place of voter registration and turnout on election day. I think this is due to the formation of a unique American Muslim identity, and how we view our religion applied to our daily lives in this country.”

Candidates and politicians are also more eager to engage with Muslim voters, McCaw said, pointing out that a mosque has become a common campaign stop for presidential candidates. However, he worries that the engagement is often only skin deep.

“Both parties like courting Muslim voters. They just don’t like engaging,” he said. “Candidates will appeal to Muslim voters, but when it comes time to do the harder work of discussing the needs for policy and institutional reforms to eliminate Islamophobia or curb US involvement in overseas conflicts that disproportionately impact Muslim civilians, there’s less of a willingness to engage.”

Muslim Americans are not the only pro-Palestine voting bloc in the US, Chouhoud said. There is also a large group of Arab Americans belonging to other religions — most of them Christian — who have been further mobilised by Israel’s invasion of Lebanon.

“A lot of Lebanese Americans also live in Michigan,” Chouhoud said. “As Israel expands its military intentions across the region, more and more of these groups, both Muslim and Christian, will be going to the polls in November with that firmly on their mind.”

Newsletter

Newsletter