Rewriting the rules: the history of Indian cinema shows the many faces of a changing nation

With seasons at the Barbican and Leeds International Film Festival, Indian Parallel Cinema is finally getting the international recognition it deserves

The 1960s were a time of great turmoil for India. First came the 1964 death of Jawaharlal Nehru, who had been the country’s prime minister since independence was achieved 17 years earlier. Then war broke out with both Pakistan and China, food prices and unemployment rocketed, and internal rebellions erupted in West Bengal and beyond. The hope and promise of a newly sovereign nation seemed to have stagnated and dissatisfaction was widespread.

That feeling was sharply reflected on the big screen. Alongside America’s New Wave filmmakers and the iconoclastic, existentialist Nouvelle Vague in France, India began to produce a rich seam of postcolonial, auteur-led movies, which coalesced into a scene known as Parallel Cinema.

From the late 1960s to the mid-90s, the country’s independent filmmakers released more than 200 features depicting the many faces of a changing nation. Their subject matter is wide-ranging, including the first example of Indian queer cinema, critiques of class and caste, feminist documentaries and interrogations of rising Hindu nationalism and Islamophobia.

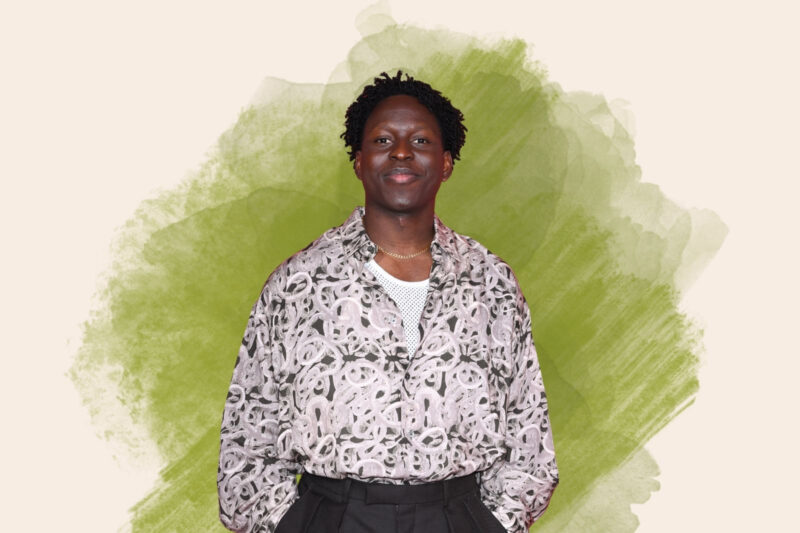

Indian Parallel Cinema produced a vast number of rich and diverse films but it is an era in global cinema history that has yet to receive the international recognition it deserves. Now, with another series planned to showcase the work of actor Smita Patil at the Leeds International Film Festival (LIFF) in November, it seems the Indian New Wave is finally having its international moment.

“It’s a very important period in South Asian cinema but in the history of film it just isn’t known about enough,” says film writer and academic Dr Omar Ahmed, who is curating the LIFF Patil retrospective. “So many of these films provide a fascinating window into a turbulent time and show a different side to Indian cinema from the commercialism of Bollywood. It’s essential that it’s given a platform today.”

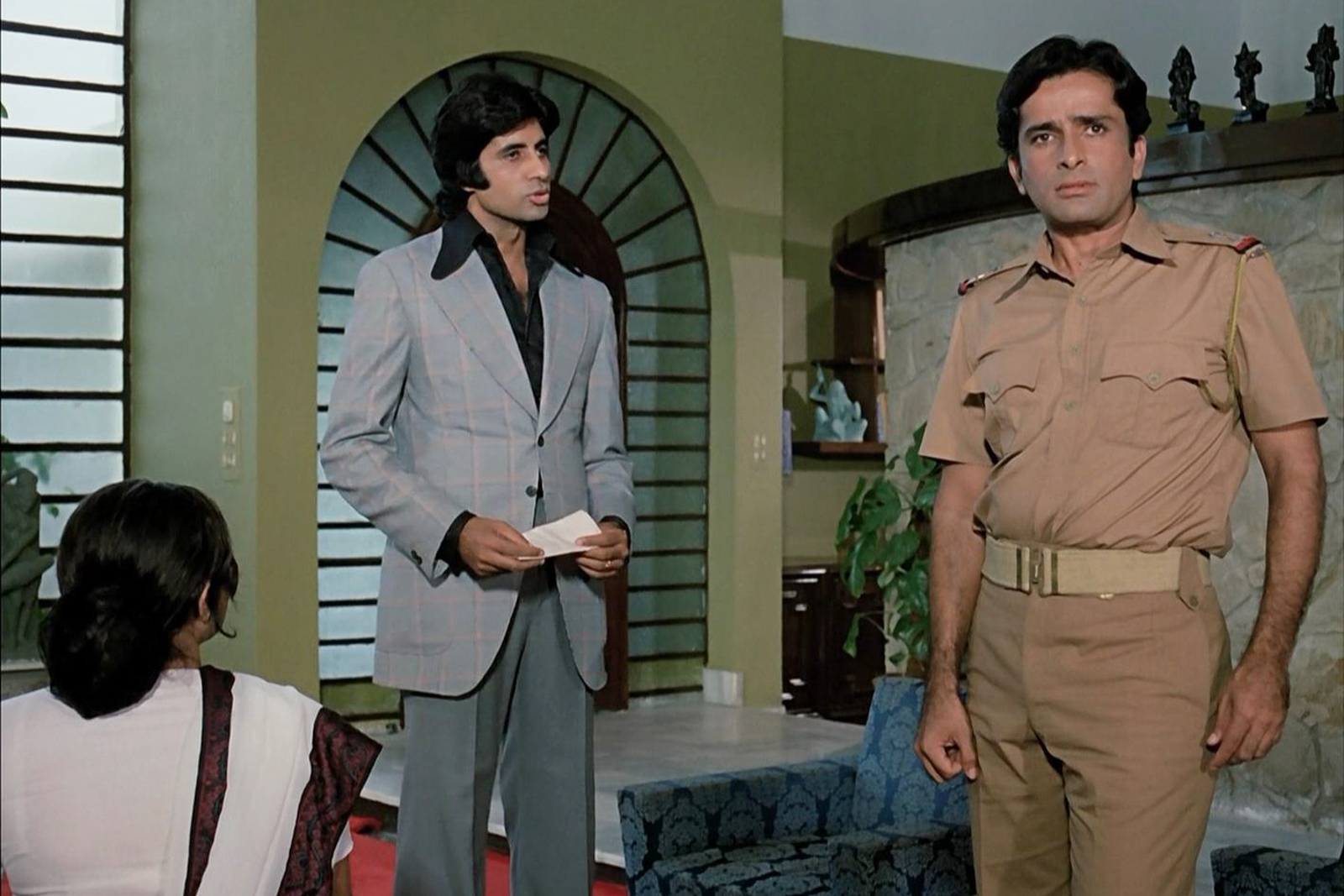

From 3 October to 12 December 2024, Ahmed is also curating a series of Parallel Cinema screenings at the Barbican cultural centre in central London. Titled Rewriting the Rules, the programme will run alongside The Imaginary Institution of India, a new exhibition of Indian art from the 1970s to the 90s. Among the 10 films selected by Ahmed is Yash Chopra’s Deewaar — which features an early, critically acclaimed performance by Amitabh Bachchan as an archetypal angry young man named Vijay. There’s feminist folklore in Mani Kaul’s Duvidha and a searing examination of the persecution of Muslims in Anand Patwardhan’s In the Name of God.

“So many things were happening in the 60s onwards to create the perfect environment for these films to be made,” Ahmed explains. “You had the birth of the Film Finance Corporation, which was the first time the state began funding low-budget films, the founding of the Film and Television Academy, which meant a new generation of filmmakers could receive formal training, and you had the backdrop of widespread social and political unrest.”

In 1966, Indira Gandhi became India’s prime minister. Under her government, India’s economy faltered and a wave of uprisings broke out, including a 1967 Marxist “peasant rebellion” in West Bengal, known as the Naxalbari uprising, and the suspension of civil liberties — now known simply as the Emergency — from 1975 to 1977.

“People’s freedoms were curtailed during the Emergency, the press was censored and political opposition was silenced,” Ahmed says. “In a film like Deewaar, which was released in 1975, Amitabh becomes a symbol of collective anger towards inequality and it taps into the failure of what Nehru had promised, producing disillusionment with authority and government.”

Ahmed explains that the opening scene of the film shows the trade unionist father of Bachchan’s character arguing for the rights of working people, which was a sentiment reflected by many in the country at the time. “It’s a mainstream film made by one of Bollywood’s greatest directors, but it doesn’t get more blatantly political than that,” he says.

Other highlights in the programme include the recently rediscovered 1971 film Badnam Basti, which is regarded as the first example of Indian queer cinema.

“It’s a beautiful film that was only rediscovered in 2019 and is so ahead of its time in telling the story of a love triangle between two men and a woman and exploring those complex gender dynamics, as well as bisexuality,” Ahmed says.

“There’s also our opening film, Interview, which came out in 1971 and produces a real break from the commercial narrative cinema of the past. It plays with a mixed media aesthetic of jump cuts and freeze frames, as well as breaking the fourth wall, all while producing a satire of the colonial attitudes that persisted into independence.”

Perhaps the film with the most resonance today, though, is Patwardhan’s 1992 documentary In the Name of God. Focusing on the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi controversy, where Hindus claimed the right to demolish a mosque in the city of Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, and build a temple on the same site, the film cuts together interviews with politicians and the public to investigate the rise of Hindu nationalism, which has since become increasingly mainstream in India.

“After the Emergency, there was a lull in financing new films because everyone was scared of censorship and political recriminations, but someone like Patwardhan still managed to produce work that presented searing critiques of every government from the 60s right up to the 90s,” Ahmed says.

“In the Name of God is a landmark documentary and one of the few cultural artefacts of the time that brings to light the difficulties that Muslim communities were facing during India’s shift towards the right. What Patwardhan does brilliantly is that he shows politicians dividing and ruling, making Hindus and Muslims hate each other so politicians can consolidate their power. Patwardhan’s work is so enduring because his critique is vast and when you watch it now, it feels like it was made just a couple of weeks ago,” he adds.

According to Ahmed, the Parallel Cinema movement began to wane in the mid-1990s, as the rise of the rightwing Bharatiya Janata party meant less funding for independent films that might critique the status quo. Meanwhile, an increasing demand for Bollywood movies from members of the Indian diaspora helped to create a new, more global-facing cinema industry.

“People have made films that are daring and critical since but it tends to be far more marginal and it can be difficult to access,” Ahmed says. “With Parallel Cinema, though, so many of these films would have been shown every Sunday on television and beamed into Indian homes. It’s a side of Indian cinema we mustn’t forget.”

Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970, runs at the Barbican until 12 December.

Newsletter

Newsletter