Looted, destroyed and erased: archivists around the world struggle to save Palestinian histories

Cultural heritage has long been a target of Israel’s war and occupation, with many archives across Gaza and the West Bank now gone forever

Over the course of a month in early 2002, during the Second Intifada, Israeli occupation forces raided and occupied the Palestinian Ministry of Culture’s six-storey building in Ramallah. When Rula Shahwan, director of the archive department at the time, and her team returned to the office after the ending of a curfew imposed on the city, everything had been destroyed.

Among the ruins were paintings, the ministry’s main server and a library, as well as the archive of Palestinian cinema held by the department. Israeli soldiers had stolen laptops, pilfered cash and removed hard disks from computers. The stench of urine permeated the office, coming from flower vases and bottles that had intentionally been left on desks.

“It was a miserable situation,” Shahwan says.

Shahwan’s experience at the archive was not the first instance of Israeli looting and destruction of Palestinian cultural heritage, the history of which stretches back to the Nakba in 1948, with the plunder of Palestinian books and manuscripts from public and private collections, to the present assault on Gaza which has resulted in the loss of many archives and cultural heritage sites. “The genocide ensures that we do not retain access to our own knowledge, our own writings, our own history,” says Mahdi Sabbagh, an architectural scholar and co-curator of the Palestine Festival of Literature, which runs events in the UK and internationally. “It’s a way to sever people from the place that they’re from.”

As of last month, Unesco has verified damage to 69 sites in Gaza since October 2023, among them archaeological areas, monuments, and buildings of historical and artistic interest. A preliminary report issued in January by Librarians and Archivists with Palestine documented the names of heritage advocates killed by Israeli bombardment. Marwan Tarazi, an archivist of Kegham Djeghalian’s photography studio — the first in Gaza — was killed in October with his wife and infant granddaughter while sheltering at the Saint Porphyrius Orthodox Church.

This erasure of cultural history has “long been an Israeli tactic of war and occupation to further limit the self-determination” of Palestinians, the report stated.

Sabbagh’s research took him to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem this summer. Copies of bulletins written by Al-Ard (The Land), a Palestinian political movement that was outlawed by Israel in the mid-1960s, were held there. But two bulletins were missing. A stamp on the copies led Sabbagh to the archive of a kibbutz in the north, where, after searching shelf by shelf, he was unable to find the papers. He learned that after the kibbutz was privatised, the bulletins held by its former library were likely to have been thrown out.

“It’s a place where our knowledge is collected, but it’s collected almost as war loot,” Sabbagh says of the Israeli archives he encountered. The bulletins were intended to be read by Arabic readers, he says, not to be placed in coffers. “My mission is to retrieve our own knowledge and to make it accessible to other Palestinians.”

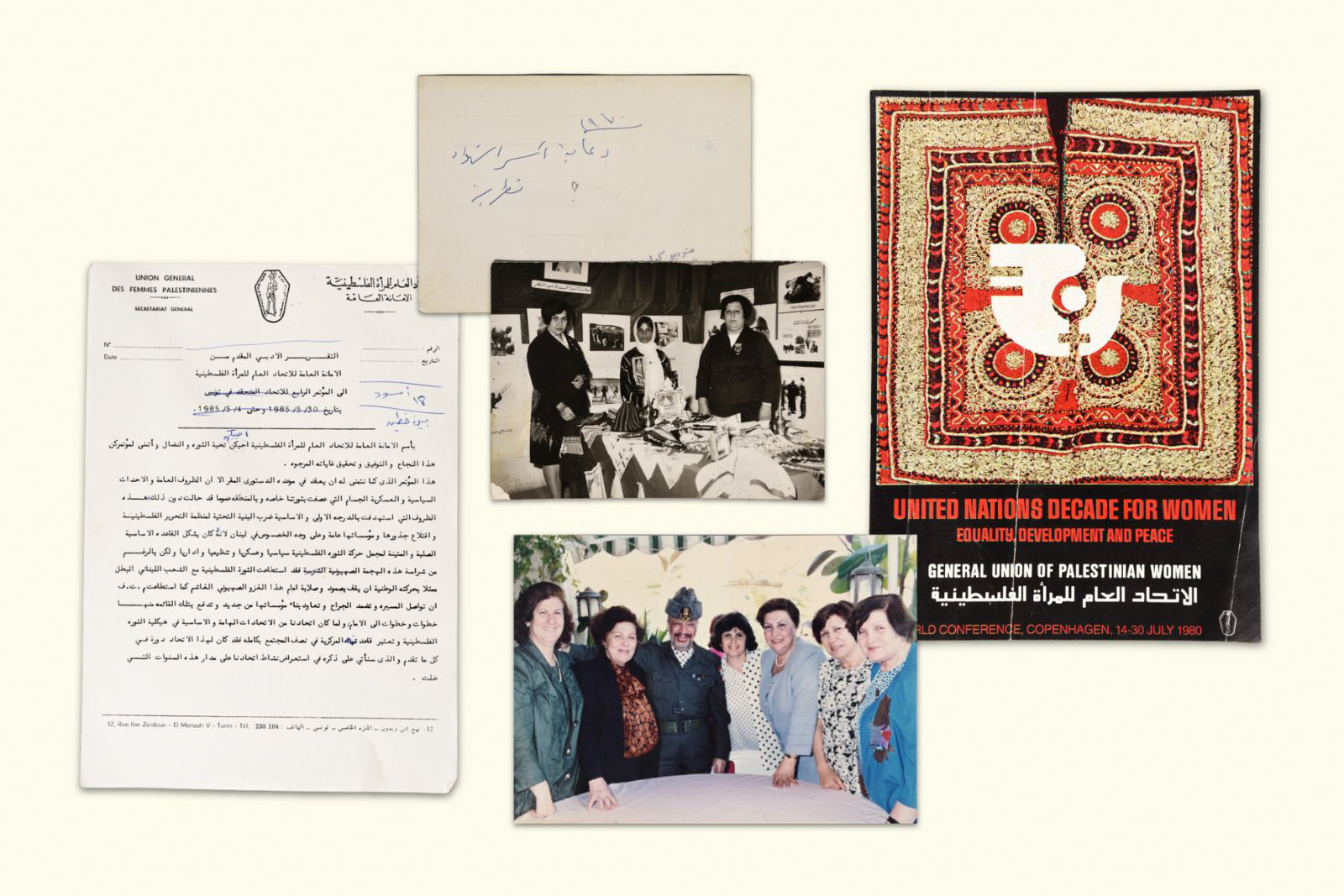

Writer and curator Alia Al-Sabi, who is currently pursuing a PhD at New York University, agrees that Palestinian researchers who can access physical archives have a responsibility to retrieve and safeguard materials, which, in her and Sabbagh’s work, speak to a history and legacy of resistance and revolutionary thought.

Al-Sabi’s work focuses on an archive in the West Bank containing the contents of Palestinian prisoners’ libraries from prisons in the Nablus area that were closed down after the signing of the Oslo accords in 1993. She first learned about the collection in 2018, during a visit home from the US where she worked as an architect and curator.

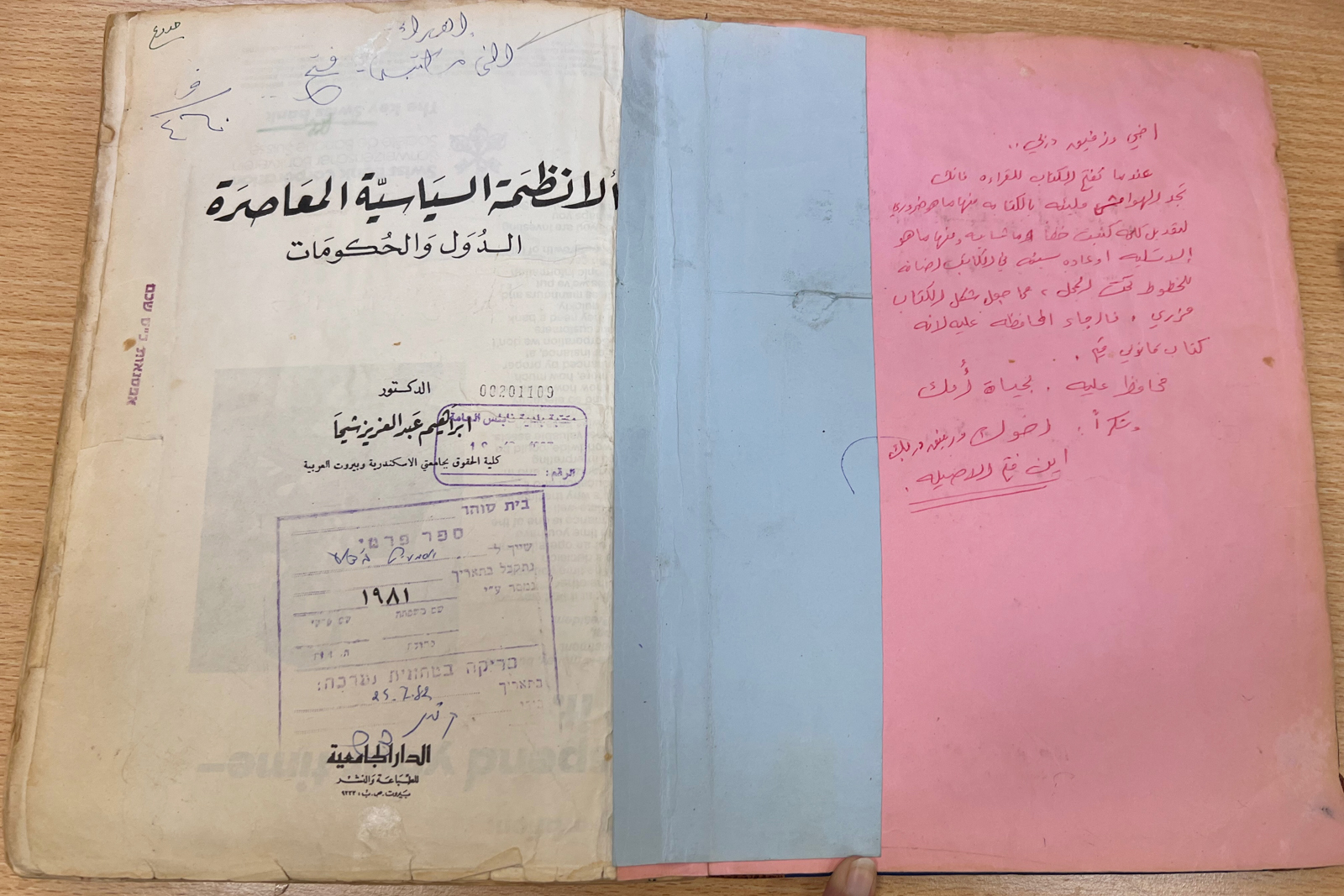

At the time, Al-Sabi had no intention of returning to academia, but she felt haunted by what she found in the archive. During that first visit, she recalled encountering a kind of patina on the books, some of which dated back to the 1970s. Among the 8,000 volumes and 870 journals housed in the library, she came across prisoners’ writings, often in the margins of the books they were reading, where they would write their names, the places they were from, and the duration of their sentence.

“I think of these gestures as marking presence in a space that tries to intensify your absence,” Al-Sabi says. “It’s a reflection of that moment in time, and how it bleeds into this moment.” One book had been carved in the centre as a means to transport letters between prisoners, written in handwriting so small that a magnifying glass was required to read them. She became fascinated by the way in which the prisoners made themselves indecipherable, circulating knowledge and information among each other without being caught by the prison authorities.

With the escalation of Israel’s war on Gaza and violent occupation in the West Bank over the past year, Al-Sabi has been unable to return to the archive. Its inaccessibility has brought into sharp relief the urgency associated with preserving its materials. If archiving in other contexts, Al-Sabi says, is associated with a slow, deliberate process, the work of Palestinian archivists and researchers embodies a fugitive quality due to the potential of Israeli looting and destruction at any moment. “When I talk about archiving, it’s more, ‘how many pictures can I take at any given visit?’” she says. “Because I don’t know if this book will still be there when I come back next time.”

In recent years, public institutions and individuals in Palestine have sought to digitise vast tranches of cultural materials as a means to address the precarity of the physical archive. The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive in Birzeit was established in 2018, and now comprises more than 300,000 endangered Palestinian documents spanning 200 years. These include family albums, political and cultural newspapers, maps, banking records, and birth and death registers. “By making this information available to everyone, we engage in a form of resistance against narratives that falsify Palestinian history,” says Islam Kamal, a researcher who recently served as the archive’s manager.

Elsewhere, the collection and digital archiving of oral histories has served to preserve narratives at risk of being lost. Refugee Chronicles is a project by a London-based researcher including more than 70 testimonies from Nakba survivors. “We all know there are certain entities out there that try to pretend the Nakba never happened, or discard the Nakba,” the researcher, who asked to remain anonymous, says. “It’s our duty as Palestinians to save these stories.”

Since last year, Shahwan, who is the director of the library and archive at the Arab American University in Ramallah, has been in contact with archivists in Gaza responsible for materials held in private collections, as well as rare manuscripts from the early Islamic era held in the collection of the Great Omari Mosque, which was destroyed in an Israeli air strike in December.

But the loss of municipality records, court documents, and the records of educational institutions that exist solely on local servers after the bombing of schools and universities, has highlighted for Shahwan the everyday implications of the archive — the tragedy of losing not only materials related to collective memory and national identity, but also those documents necessary for daily — and future — use. Personal memory in the forms of photo albums and family records are gone. “It is under the rubble,” Shahwan says. “The things that still keep us linked to our past.”

One of Shahwan’s frequent collaborators, an archivist named Fadi Abdel Hadi, spoke to her five weeks after the beginning of Israeli shelling and bombardment in October last year. Abdel Hadi had been a collector of artistic works, plays and music, as well as materials belonging to the media department of the Palestine Liberation Organization. He told Shahwan, who had asked him earlier to preserve the film materials in his possession, not to worry: “I put all the hard disks and cables in one bag and I told my wife that this bag is more important than our clothes.” Shortly afterwards, he wrote to Shahwan on Facebook Messenger, informing her that his house and part of the archive he had spent years collecting were destroyed in an Israeli air strike. “He lost his whole legacy,” Shahwan says.

Newsletter

Newsletter