Naqqash Khalid Q&A: ‘The history of the camera is deeply colonial’

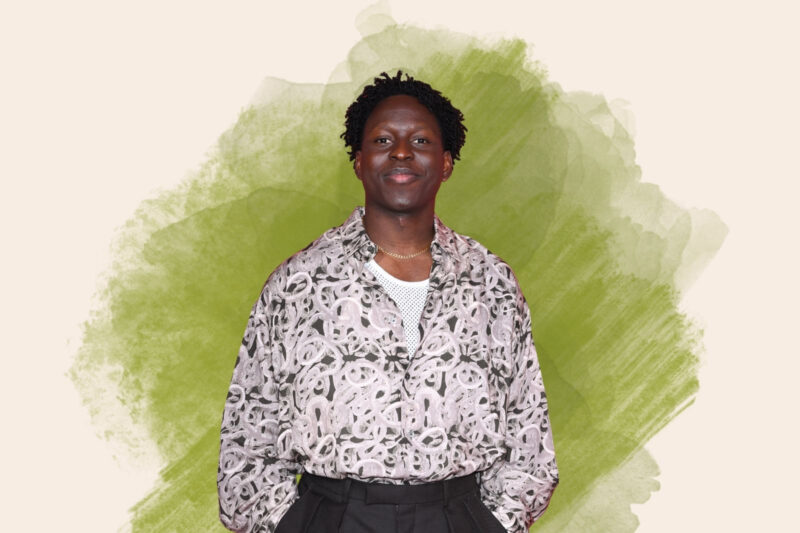

Writer and director Naqqash Khalid spent 10 years making his debut feature, In Camera. Photograph by Lucia O’Connor-McCarthy courtesy of Naqqash Khalid

The In Camera writer and director on racial identity, experimental film-making and confronting the imperial legacy of cinema

For Naqqash Khalid, film-making is a medium that holds infinite possibilities. Previously an English literature lecturer at Salford University, Khalid is fascinated by stretching the limits that define conventional storytelling.

The 30-year-old’s debut feature, In Camera, follows young actor Aden (played by Nabhaan Rizwan) who is haunted by the superficial pressures of the entertainment industry.

Khalid’s experimental direction plays with these pressures and micro-aggressions through subtle references to Aden’s racial identity and background.

There is also a deeper dialogue with colonial forms of representation, and the camera’s historical use as a weapon for imperialism, which Khalid simultaneously engages with and rejects. In Camera boldly showcases the fractures that exist within modern life, ultimately leaving you with more questions than answers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you first decide you wanted to make movies, and what was your journey?

As a kid, I had this really cheap camcorder my mum bought me, and I used to make little sketches on that. I also remember watching Scooby Doo, the live action, when I was six. It was the first film I ever saw in the cinema, and I just thought, whatever these people are doing, I want to do this.

But during that period between childhood and coming into adulthood, I didn’t really see it as an option. For some reason, I just didn’t think that’s what you could do. I studied English at university, but I kept thinking I would love to make a film. So I just ended up figuring it out. I never went to film school — I’m completely self-taught.

What do you love most about film-making and your role as a director?

Making a film requires you to interact with people in a really deep and intimate way, and I think that’s so unique to film-making. I don’t think such a collaboration works in any other medium quite the same way.

There’s something really unquantifiable about how beautiful it is when you come together with people and try to articulate something so personal. You’re working on ideas that have preoccupied you, whilst turning to others and engaging in the ideas they have. It’s like you have a certain frequency, and your job is to get other people to tune into it.

It’s a bit like being a kid. Some people grow up and some continue playing. Making a film is like this continuous, collective play.

Where did the idea for In Camera come from and how has the concept developed over time?

I had the idea in my final year of university, and then we first revealed it when I was 30, so that’s 10 years now. I created a document that didn’t really look like a script — it had memes and paintings, and hyper-specific dialogue and scene direction. It was a culmination of many ideas over time, usually just random notes on my phone. Then, I slowly frankensteined them into something that felt like a structure.

But I had to undergo a process of decolonising my own mind while writing this script. As minorities, I don’t think we automatically start from our perspective. We have to go through a period of unlearning to get to the core of what we want to express.

There’s something quite western about the classic three-act structure, and focusing on a single hero going on a journey. It just didn’t sit right with me or feel like the shape that best represented the narrative I wanted to tell. I think every film should be an invention, rather than just inheriting a structure.

The film is abstract and experimental in its style. Why was it important for you to tell Aden’s story in this way?

I wanted to direct something that would be formally challenging, not just for the sake of it but because this character was asking for it.

I was really interested in tessellations, repeating patterns, geometric abstractions, and I was looking at a lot of paintings by South Asian Muslim artists, which got me thinking about narrative structure as being circular instead of linear. Like Aden, who constantly has to shift and change to please this outsider gaze, the film is constantly changing. It’s a teen drama, it’s a racist, terrorist drama — you can’t really pin it down.

How have you found navigating British cinema as a Muslim director?

Film-making is a weird medium because you’re inheriting all these tools. I was hyper-aware that these tools were not built for me — in fact, they’ve been used against people that look like me. A lot of film-making equipment is developed in the military, so the history of the camera is deeply colonial. When you’re using colonial tools to tell a story, you are constantly in a dialogue of what that history is wrapped up in.

Often when we enter these spaces, we have to reclaim our identities but, at the same time, as soon as you start thinking about yourself through outsider labels, you risk self-orientalising.

If I think about myself as an Asian, Muslim man from an outsider point of view, I’m going beyond myself and my own gaze and lens. My white, male counterpart isn’t thinking about how his whiteness informs his work. He’s just given the privilege of being told he’s the default, and doesn’t think about himself in any other way. So similarly, I no longer “other” my own perspective. I’m going to enter this medium with my perspective as the default.

In Camera is in UK cinemas now. Read Leila Latif’s review.

Newsletter

Newsletter