Sickle Cell Awareness Month brings vital attention to an often overlooked disease

Recent advances in treatment have made headlines, but lack of funds for research and widespread misconceptions still create obstacles for patients

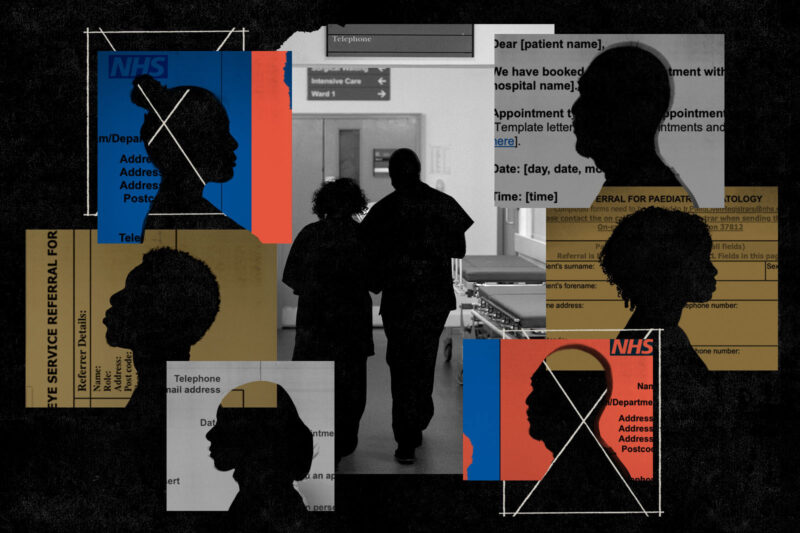

Around the world, the first week of September marks the start of Sickle Cell Awareness Month. Sickle cell disease is an inherited blood disorder affecting around 17,500 people in the UK and is particularly prevalent in those from African and Caribbean backgrounds. While great strides have been made in both the understanding and treatment of the condition, researchers and patients believe there is still much more to learn.

Sickle cell disease affects the haemoglobin in red blood cells and restricts their ability to carry oxygen around the body. In those living with the condition the cells, instead of being round and disc-shaped, resemble a crescent moon or sickle. That malformation can cause them to stick together and create blockages in small blood vessels, leading to chronic anaemia, increased risk of infection and periods of intense pain. Commonly referred to as crises, such episodes can be life-threatening and frequently require hospital care.

In recent months, sickle cell has made headlines as a central element of the storyline of the hit Netflix show Supacell, which racked up more than 18m views in its first few weeks. In May, a significant medical advance was made when a “life-changing” drug named Voxeletor was recommended for use by the NHS. The drug prevents malformations in red blood cells and patients have reported increased energy and a significant reduction in pain. Around 4,000 people in the UK were set to benefit from it straight away.

Most treatment of sickle cell focuses on pain relief and preventing complications with blood transfusions, using medications including antibiotics to prevent infection; and hydroxycarbamide, a drug better known for its use in cancer care, to reduce complications such as blocked blood vessels. However, the options remain limited.

“Hydroxycarbamide doesn’t work on everyone, some patients have life-threatening complications from blood transfusions and Voxeletor is still a new drug,” says Dr Steven Okoli, a consultant haematologist at Imperial College NHS Trust.

Sickle cell remains the UK’s fastest-growing genetic disorder. Compared to other inherited conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, experts also believe that treatment of the condition is underfunded and under-researched.

“The most damning thing about sickle cell is that there is very little treatment available for a disease that we’ve known about for the best part of a century,” says Okoli. “We only have a handful of treatments for the disorder, some of which are antiquated and most of which were not specifically designed for the condition.”

The only possible cure is a stem cell transplant. However, such treatment can only be received by children and adults who have a full-match sibling, which is rare, according to Okoli.

Growing up, Zainab Garba-Sani did not experience many of the symptoms of sickle cell and often forgot she had it at all. As she got older, though, she began to experience more complications. Now, she is in the fortunate position of gearing up for a stem cell transplant.

“It’s been a lot,” she says. “I’ve tried all the other medications, but once you’ve exhausted all your options and they don’t work for whatever reason, that’s it. Stem cell therapy is the only curative kind of treatment.”

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) is now reviewing the use of gene-editing therapy for sickle cell patients and has already approved the treatment for those with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia, another inherited blood disorder.

Gene editing involves modifying the stem cells of a sickle cell patient, so their body produces functioning haemoglobin. The stem cells are collected and edited outside the body, before being transplanted back into the patient.

As sickle cell mostly affects people from African or Caribbean backgrounds, some believe this contributes to the lack of research and funding.

“Comparisons are often made between sickle cell and cystic fibrosis, which predominantly affects white people,” says Okoli. “There are about 30% more sickle cell patients than cystic fibrosis patients and 500-odd treatments have been developed for cystic fibrosis, whereas sickle cell has three. Despite that clear disparity, there is so much more investment in cystic fibrosis, so it does beg the question as to why.”

A 2021 report by the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on sickle cell and thalassaemia showed that research into the condition is consistently underfunded when compared with other genetic disorders. Further research by Imperial College London has shown that the National Institute for Health and Care Research and UK Research and Innovation awarded cystic fibrosis research around £67m more than sickle cell disease.

The same APPG report looked into avoidable deaths and failures in the care of sickle cell patients, highlighting the role racism played. One patient, speaking about the hurdles they faced when seeking pain relief, told the APPG that some healthcare professionals “jump to the conclusion that we’re all junkies and not in pain at all”. Another said they believe sickle cell patients are perceived as “difficult” and viewed as potential drug seekers. Labour MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy also contributed to the report, highlighting research that shows some medical staff “believed that Black people experience less pain”, causing further negative attitudes towards sickle cell patients.

“That report showed that the quality, investment and research in sickle cell care are woefully inadequate,” says Okoli. “It also stated that part of the reason for this is because of racism. Many sickle cell patients and doctors have thought this, but it had never been said out loud like this before.”

The lack of understanding of the condition within the healthcare system can also lead to uncomfortable experiences for patients. From birth, Faridah Salami, 26, would go to King’s College Hospital in Camberwell, south London, when experiencing a crisis. The hospital is known for treating a large number of sickle cell patients and has the longest-established paediatric sickle cell and thalassaemia clinics in the UK. When Salami and her family moved to Croydon, she found that staff at her nearby hospital were less understanding of her condition and the treatment required.

“Sometimes all I needed was a blood transfusion or morphine, but I’d find they would drag out the whole process,” says Salami. “I’d end up being in hospital for a lot longer than necessary.”

Salami says that she often felt as though she had to prove that she was actually unwell and would end up having to explain her condition to doctors when in A&E. “When you’re experiencing that much pain, explaining your condition is not a priority,” she says.

New medical developments and a gradually growing awareness of both sickle cell itself and the needs of patients with the condition do, however, provide some hope.

“I’m optimistic that we’re starting to move in the right direction and that people are showing more and more interest in this area,” says Garba-Sani. “If we can make things work for sickle cell, we can probably make things work for so many other populations.”

Newsletter

Newsletter