Muslim and minority artists fear for their survival in Geert Wilders’ Netherlands

After triumphing in the 2023 Dutch elections, a far-right cabinet is withdrawing support to both arts and cultural activities

Ahmad Joudeh broke into a cold sweat when he saw a vandalised poster of himself in Amsterdam with a bullet hole drawn on his forehead. The flyer advertised the professional dancer’s role as Pride Ambassador at Amsterdam Pride last July, which should have been a defining moment in his new life — a stark contrast to the refugee camp in Syria where he’d grown up. But the violence of the graffiti brought all the fear back.

“Queer, Muslim, refugee — these labels put me in danger, not only in the camp but also here in Europe,” said Joudeh, 34, who was granted a Dutch visa in 2016 to perform with the Dutch National Ballet. After the defacement of his poster, the escalating hostilities he faced in Europe, and the success of anti-Muslim populist Geert Wilders in the November 2023 elections — his far-right Freedom Party (PVV) secured 37 of 150 seats in the vote — Joudeh reached his breaking point. A Dutch national, having obtained a Dutch passport in 2021, he is now temporarily in San Diego, California, training with the Golden State Ballet while contemplating his next move.

“I didn’t feel protected enough in the Netherlands, especially with what is happening now,” he said. November was the first time Joudeh had voted. “It was amazing to feel that you can make a change. But, obviously, not a big change, because someone like Wilders wins and destroys all your dreams.”

Wilders now has a sizable political presence in the Dutch government and poses a real threat to refugee and immigrant lives in the Netherlands, having espoused Islamophobic and anti-migrant views throughout his political career. He has compared the Qur’an to Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf and called for bans on both mosques and burqas; he failed to impose the former but in 2019 achieved a partial ban on the latter.

After his election success, Wilders was tasked with forming a government with the 15 other parties that secured seats. To do so, he softened some of his more hardline positions to gain broader support and form a coalition, scrapping proposals to ban “expressions of Islam” and dual nationalities. He also stepped back from pursuing the role of prime minister, backing independent Dick Schoof for the role. Schoof’s cabinet is, however, dominated by rightwing and far-right ministers, and the PVV’s anti-Islam stance has never held so much influence.

Wilders has also criticised excessive spending on the arts, which he calls “leftist hobbies”. One of the first actions of his new coalition government was to announce plans to raise value-added tax (VAT) on arts and cultural activities. The rate for museums, theatres, books and festivals is set to increase from 9% to 21% by 2026, with an aim to generate an estimated €2.2bn for the treasury. Only cinemas and amusement parks have been spared.

Filmmaker Vincent Soekra organises the annual cultural festival Kwaku. When it first started in 1975 in Bijlmer — a neighbourhood in south-east Amsterdam with a large migrant population mostly from the former Dutch colony Suriname — Kwaku was free. By 2011, it had grown so large that it was no longer able to meet safety and security regulations and closed. When Soekra stepped in to bring the festival back to life in 2013, he was forced to introduce entrance fees but has tried to keep them as low as possible. At €15 a day, it’s still one of Europe’s most affordable festivals.

Kwaku promotes inclusivity, especially for minority groups. “Everybody is welcome,” Soekra said, stressing the importance of community cultural events like his in combating racism and xenophobia. “If you know more about each other’s cultures, you’ll gain a better understanding of the diverse groups living together here.”

Now, as new tax hikes raise costs for all event organisers, Soekra fears he will be forced to raise ticket prices and exclude the very audience he had fought to include. He believes the government is deliberately targeting the arts in a further attempt to sow division in the country. “They put people on sides and show no empathy towards others,” he said.

When producer and scriptwriter Başak Layiç fled Istanbul for the Netherlands following the attempted military coup in Turkey in 2016, she found refuge in an Amsterdam riverfront community centre founded by Iranian brothers. Mezrab is largely volunteer-run and offers free events including storytelling nights and jam sessions. “Mezrab started in an Iranian family living room. It’s really grassroots, which makes it beautiful and genuine,” Layiç said. “It feels like a big family because it started as a family.”

From there, Layiç built a creative career in the Netherlands. She debuted her play The Millennial Immigrant, which explores the challenges of finding acceptance in new homes, at the Amsterdam Fringe Theatre in 2020. She doesn’t follow Dutch politics closely and neither do her friends — “maybe it’s because we come from traumatised countries; we’re done with it” — but she was shaken by the 2023 election results. “Some of us joked, ‘I left one fascist government to end up in another fascist government. So, where do you go?’”

Layiç relies on financial support from Dutch theatres, but many have paused funding since the government announced the tax increase. She fears she may have to leave the country if funding continues to dry up. “Theatres receive state funding every four years, and now they don’t know what they’ll do,” she said. “People are worried.”

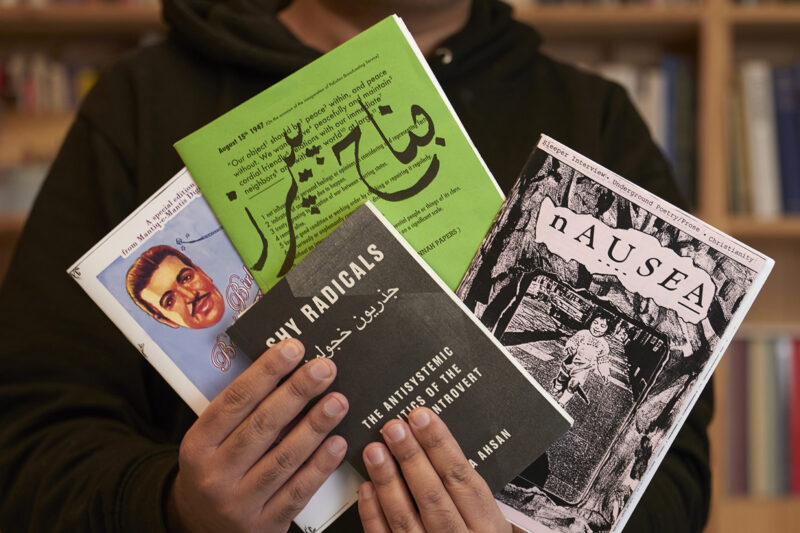

The cultural sectors under threat by the new government have started to group together in protest. On Amsterdam’s Haarlemmerweg street, known for its independent bookshops, several stores have flyers posted on their windows featuring a book with a broken heart on its cover and the text “21% VAT is a worthless idea”. The poster asks supporters to sign an online petition calling on the government to drop the tax. At the time of writing, it had more than 300,500 signatures.

Famous Amsterdam venues including Paradiso and Melkweg, known for hosting both emerging and established artists as well as popular events such as Disco Arabesquo — Amsterdam’s premier Arabian club night — have also expressed concerns about the new tax. Speaking to the Dutch press, they warned that increased ticket prices would attract only affluent audiences and prevent lesser-known artists from selling tickets.

In the theatre world, which has long struggled to attract a diverse audience, the fear is the same. “Already the audience that we see is mostly white, middle-aged people. It’s obvious it’s going to get even worse,” Layiç explained.

In San Diego, Joudeh says he hopes to be able to return to the Dutch stage at some point but for now he is reluctant. Many of the other dancers he knows have moved to Germany, which at 7% has the lowest VAT on arts in Europe. “When the storm is happening, just get refuge until everything settles. Then you can start building again,” he said.

Newsletter

Newsletter