Can the Greens hold on to their Muslim voters?

Soaring numbers of Muslims voted Green at the general election. But the party has seen boom and bust before, and Gaza may no longer be a defining issue by 2029

The Green party’s popularity among British Muslims soared this year, helping propel it to its best-ever general election result. It won nearly two million votes in July, securing not just a long-hoped-for second parliamentary seat, but also a third and a fourth.

But there is a cautionary tale for the Greens from the days of their last big surge.

The party took more than a million votes for the first time in 2015, with an emboldened Caroline Lucas predicting “a real movement outside parliament” would follow to push for electoral reform. Instead, its support dropped by more than half in the 2017 general election as both Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn’s more radical progressive agenda drove Brits back into red and blue party lines. The period that followed for the Greens saw leadership changes, Lucas’s resignation as the party’s only MP, and an ugly transphobia scandal.

Whether the party can avoid the fate of 2015 and hold onto its gains this time round is the question now facing co-leaders Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay — and core to that is the effort to keep British Muslims on side.

“There was a general assumption that Muslim voters would vote Labour, and they did very loyally for many, many years,” said Andy Cooper, a Green party councillor in Kirklees who ran for parliament in July. “That’s no longer there, and that will not be easily regained.”

Muslim support was at least part of the reason the Greens took the Bristol Central seat, where there is a significant Somali community. It was also likely behind strong second- and third-place showings in constituencies around the UK with large Muslim populations, among them Sheffield Central and Poplar and Limehouse in east London.

Cooper came second in his own seat, Huddersfield, with 26% — a rise of 22.5 percentage points that put him within 4,500 votes of the sitting Labour MP. This could make Huddersfield a tempting target for the Greens at the next general election if they can keep up the momentum.

But Cooper acknowledges that a wide diversity of Muslim voters, united by dismay at Israel’s bombing of Gaza, turned out for the Greens at this election in a way that might be difficult to replicate — from its more natural base of liberals and leftists to traditionalists who might sit less comfortably with the party’s policies on some social issues.

“We had an organisation called the Huddersfield Community Action Group, which roughly represented more traditional [socially conservative] Muslim voters, and they supported us and helped us with our campaign,” he said.

The group endorsed Cooper in May, before the election was called, after assessing his and other candidates’ views on issues including Palestine, housing, poverty and discrimination, and their track record as local representatives or members of the community. But the group specifically says it backs “individuals, not parties”, and Cooper is not naive in thinking that future disaffected Muslim voters will necessarily come to the Greens, or that those who backed the party in July will stay.

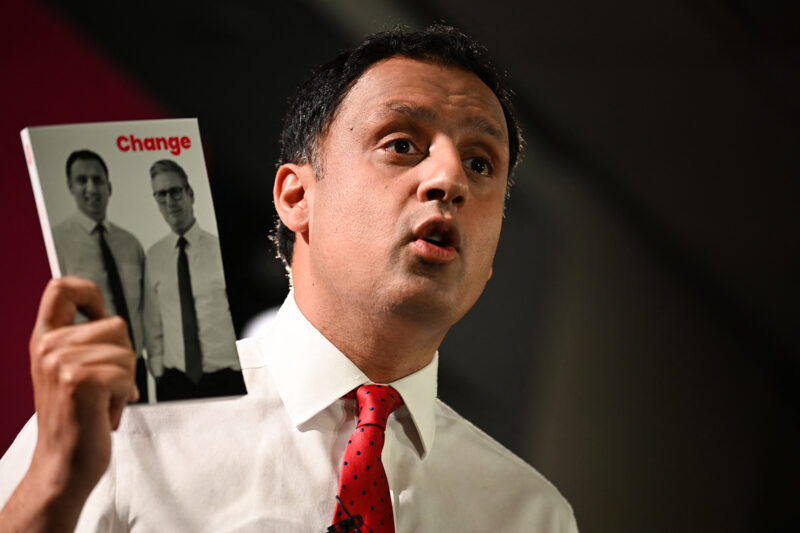

Labour’s stance on Gaza was a significant factor in driving away Muslim voters in July’s election. Hyphen’s polling in May and June found Gaza was the number-one concern for more than a fifth of Muslim voters, and among the top five concerns for 44%. Our data suggested nearly a tenth of Labour’s 2019 Muslim voters were planning to back the Greens in 2024, with others switching to the Liberal Democrats or independent candidates — although Labour’s overall Muslim support was relatively stable, with former Tory-voting Muslims now falling in behind Keir Starmer to fill the gaps left by those on the left.

But Gaza was not the only reason why Muslims turned away from Labour. Policies such as retaining the two-child benefit cap and Starmer’s comments about deporting more people back to Bangladesh likely further damaged the party’s relationship with Muslim communities. While Labour in government has yet to move on scrapping the two-child limit, there is pressure both within the party and from charities to end it as soon as possible, and it is possible that neither Palestine nor Starmer’s comments about Bangladesh will be so pressing come the next general election in 2028 or 2029.

The Iraq war cast a shadow over the 2005 election, costing Labour a significant amount of its Muslim support base. But by 2010, Iraq was deemed “very important” by just 3% of voters. Palestine could remain high on Brits’ agenda if the conflict does not de-escalate, or if the UK becomes directly involved (say, for example as part of a peace-keeping force), but five years is a lifetime in politics.

Another thing that will likely have changed by the time of the next general election will be the Green party itself. A cohort of motivated activists from Muslim communities have joined in the past year and will be looking to make their mark on it, including by appealing more to Muslims.

Among them are Asma Alam and Fesl Reza-Khan, who signed up in November last year and met through the local party in Manchester shortly afterwards. “The Green party made sense because they were very raw, very good people trying for change,” said Alam. “And I just felt very comfortable in a place where there was compassion.”

The pair decided that they wanted that message to get to more Muslims and created a Muslim Greens group, gathering up members and activists across the country to support each other and be a voice for Muslims in the party. They scoured lists of council candidates for people with Muslim names, established a social media presence and used word of mouth to reach new Muslim members.

But there is a long way to go. While Alam found the party open to change, it was still very white, and fewer than a dozen of the party’s nearly 800 councillors were Muslim. That number grew following May’s local elections, and now includes the first Greens ever elected in Newcastle, Hyndburn and Bolton, propelled in part by anger over Gaza and more Muslims voting Green. The next set of local elections in 2025 will provide an early test for the resilience of the party’s new backing, but will mostly take place in Conservative-dominated county councils. Only a handful of areas with significant Muslim populations are voting next year, so the scope for Green successes may be limited.

Competition from independent candidates, empowered by the election of five MPs in July, and from George Galloway’s Workers Party of Britain, is also unlikely to go away.

Reza-Khan stood unsuccessfully as the Green candidate in Oldham East and Saddleworth at the general election. He was up against three far-right candidates while facing pressure from the Workers Party for pro-Palestine votes. “All these small fringe parties, they have quick-fix solutions, which, following the years of crisis that our community faced — whether it was through terrorism incidents, Prevent, grooming gangs, right-wing violence, and, of course, Gaza — it’s quite an attractive option,” he said. By contrast, he hopes the Green party can “mature” alongside its Muslim members and build loyalty on a range of issues.

But others are calling for the Greens to cooperate with other parties on the progressive left rather than seek to consolidate their own gains.

“It is clear that they [the Green party] have made huge dents into Muslim communities,” said Abubakr Nanabawa from The Muslim Vote, a campaign group that aimed to organise voters to back pro-Palestine candidates.

He told Hyphen the Greens were a “powerful force for good”, highlighting their progressive policies on austerity, housing and poverty, as well as their stance on Palestine. However, he believes the Greens, and all progressive parties, need to be more strategic and stand joint candidates in a similar way to France’s New Popular Front, which scored a surprising victory over the far right and centrist parties to win the country’s parliamentary election in July.

“People like Leanne Mohamad could have won their seat if the Greens had stood back,” said Nanabawa. Mohamad took on Labour bigwig – and now health secretary – Wes Streeting in Ilford North, standing on an explicitly pro-Palestine platform, and lost by just over 500 votes. The Green candidate, Rachel Collinson, took nearly 1,800.

Another challenge comes from Labour itself. It’s likely the party will respond to the loss of support among Muslim communities, and it has already appointed prominent Muslim Labour MPs to ministerial roles. On the other hand, it is possible that Labour’s remaining Muslim voters will also begin to look elsewhere, having seen the success of other parties and candidates as proof of concept.

For Cooper, the next big election is the Kirklees-wide council poll in 2026. Dozens of boroughs and metropolitan districts will elect some or all of their councillors the same year, making it a key date for measuring the stability of the Green vote — more so than the 2025 local elections.

Shahnaz Ahsan is among the former Labour supporters whose backing the Greens now need to retain. Ahsan — a food writer and Hyphen contributor who lives in the Tory/Labour marginal seat of Keighley and Ilkley — said she and her family had voted Labour prior to 2024, but that she had gone Green to send Starmer a clear message about his stance on Gaza. The Tories narrowly held on to the seat.

It seems, though, that her vote is still Labour’s to lose rather than the Greens’ to keep — an attitude that may make it hard for the smaller party to consolidate its new base.

“I’m really viewing the next four years of Labour as them proving themselves,” she said. “To me. I think for too long, they’ve assumed that they’ve got our votes.”

Newsletter

Newsletter