Am I failing at raising a trilingual child?

For second-generation immigrant children, our parents’ languages are so much more than mere spoken words; they are the keys to our culture and heritage

On a balmy summer afternoon my younger brother and I are sprawled on my sofa watching the latest Mohamed Henedi film on Netflix. My two-year-old son Ammar sits on the living room floor playing with his In the Night Garden toys. I ask my brother in Arabic — my second language — why Egyptian gangsters always have ridiculous names like Sambo, and he responds in Arabic that he has no idea. Ammar lays down his toys, raises his eyebrows and shoots an exasperated look at me. “What language are you speaking Mummy? Speak in English!” It’s not the first time Ammar has heard me speak in Arabic, but nevertheless, I was surprised that the sound of me speaking a foreign language seemed to annoy him so much.

It’s also not the first time Ammar has told off a family member for speaking in their mother tongue. My Pakistani mother-in-law has tried her best to converse with him in Urdu in the hopes his toddler brain will soak it up like a sponge as scientists say they’re supposed to, but she is constantly rebuked. “Dadi! Speak in English!”

According to Dr Patricia Kuhl, research scientist and co-director of the Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences at the University of Washington, our brains will never be better at learning a second language than they are up to the age of three. I only have three months left until Ammar’s third birthday, so if that’s true my husband and I have failed at getting Ammar to speak Arabic and Urdu.

It’s not like I haven’t tried. I put plans into place even before Ammar was born. By the time he was the size of a pear, I had already stocked up on Arabic flash cards and translations of The Very Hungry Caterpillar and We’re Going on a Bear Hunt. When Ammar was 18 months I had the YouTube channel Kalam Kids, the Arabic diaspora’s answer to Ms Rachel, playing every day in the hope he would soon be greeting family members with “marhaba”.

I’ve counted to 10 in Arabic with Ammar and taught him how to respond to “ismik eeh” (what’s your name) with “ismi Ammar” (my name is Ammar) more times than I can count, but he looks at me blankly.

“But you’re part Arab, I want you to learn Arabic,” I always respond gently. “No!” he will say adamantly. I know I can’t force him to learn, remembering how resentful I had been as a child when I was forced to go to Arabic school on Saturdays.

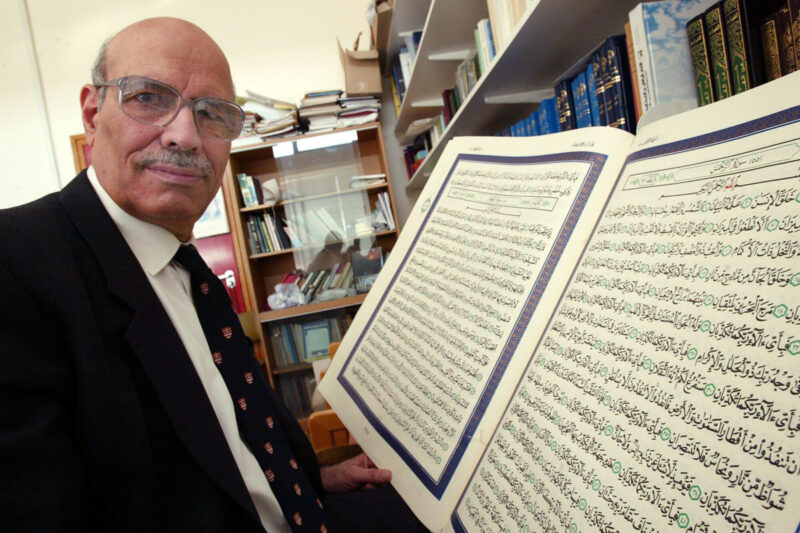

As a parent, you often want experiences for your children that you didn’t have. I did not grow up bilingual — my Egyptian father did not speak to me in Arabic when I was a child, and later, when we moved to Qatar, I had the much harder task of learning the language as a teenager. Though Arabic is part of my identity now, the relationship I have with it will never be the same as English. I still feel as if I approach the language as an outsider looking in. For example, I will never be able to read an Arabic novel in the same way I inhale an English one.

For second and third-generation immigrant children in Britain like me, our parents’ languages are so much more than mere spoken words; they are the keys to our culture and heritage. For me, being able to read and understand the Qur’an in its original Arabic form has an entirely different and profound spiritual dimension to reading a translation. Arabic is also an anchor that fastens me to my Egyptian heritage. I wish for Ammar to have this sense of belonging with both Urdu and Arabic. I don’t want him to hit his 20s and be at the crossroads of questioning his identity like so many of us third-culture children have had to endure — not feeling British, but not really feeling Asian or Arab. Yet still, we live in a country where speaking a foreign language is often seen as a refusal to integrate.

I know I am not alone in my struggles to raise a trilingual kid, as increasingly families become more mixed. Perhaps it is unfair of me to want Ammar to speak three languages when I barely grasped two myself.

Parents often feel like we are failing in some way. Our social media feeds are overloaded with parenting experts and mum-influencers all claiming their method of teaching children a second language is foolproof. In my search to find out if I am doing enough for Ammar, I found a 2017 study from the National Library of Medicine, saying that simply exposing babies and toddlers to other languages was sufficient for their brains to retain the language’s phonological patterns, making it easier to learn as an adult.

So I will continue to speak to Ammar in Arabic in the safety of our home. And he will continue to overhear my husband speak to his parents in Urdu. Arabic music will still ring through the walls of our house, and we will sit together on the sofa watching Arabic films. And perhaps one day soon he will cry for his bottle with, “biddi maai!”.

Newsletter

Newsletter