Nuri Bilge Ceylan finds beauty in the most desolate place in his poetic epic About Dry Grasses

The Turkish director has stayed away from the mainstream in 30 years of filmmaking, always showcasing his true artistry. His new film is no exception

When it comes to celebrated directors whose filmographies include a Palme d’Or and who have represented their country at the Academy Awards more times than you could count on one hand, you’d expect their name to be known outside of cinephile circles. But the Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan, born in Istanbul in 1959, is not well-known by mainstream cinema-goers — perhaps because he’s yet to make an English-language film or shrink gargantuan running times to encourage more mass appeal. Given the stunning quality of his filmography, his alternative profile has stood him in good stead, adored by those in the know and free to not compromise his vision under the glare of Hollywood scrutiny.

On the surface, his latest film, About Dry Grasses, which reaches UK cinemas on 26 July, seems like prototypical Ceylan. Celebrated at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, it’s a sprawling, poetic epic looking at the disenfranchised and desperate in areas of the world where cinema rarely ventures.

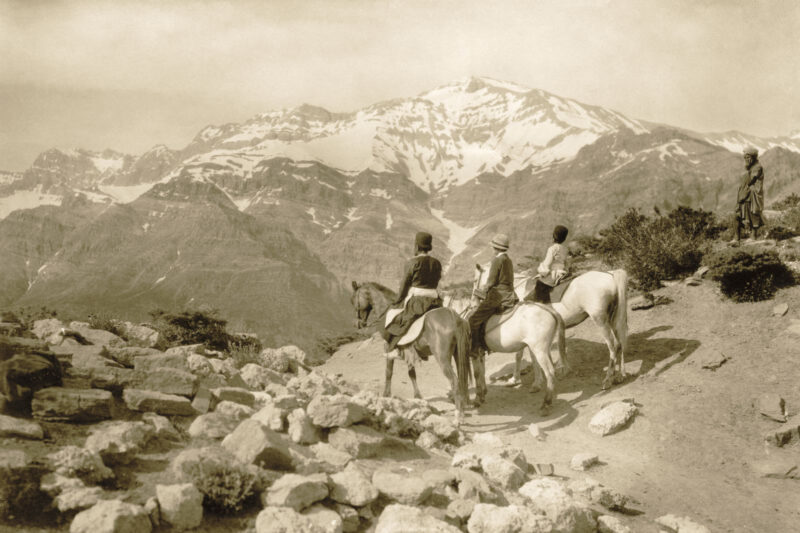

In this case, we are in eastern Anatolia, filled with rocky mountain vistas dusted by snow. Over three hours and 17 minutes, we are trapped in a cruel winter devoid of physical or emotional warmth, and art teacher Samet (Deniz Celiloğlu) is finishing out the school year, dwarfed by the dramatic landscape he begrudgingly inhabits. True to Ceylan’s tradition of complex antiheroes, Samet is a profoundly unlikeable and unsettling protagonist who treats his colleagues and romantic interests with apparent disdain. He cruelly discourages his students’ ambitions by letting them know none of them are fit to be true artists, and will do little more than the drudgery of farm work. Worse still, his relationship with his favourite student, Sevim (Ece Bağci) enters into disturbing territory.

Whereas in many of Ceylan’s previous films the problematic protagonists have an element of redemption, in About Dry Grasses he increasingly distances himself from Samet. It’s Samet’s colleague Nuray (Merve Dizdar) who becomes the truth teller through which Ceylan seems to speak. No wonder then, that it was Dizdar who Cannes awarded their top acting honour. She is ultimately the soul of the film, having overcome the trauma of being permanently disfigured by a suicide bomb and able to cut down Samet’s bullshit when he pontificates on political issues, as the unrelenting blowhard he is exposed to be.

This is a brilliant film regardless of whether a viewer (a patient viewer given the running time) is familiar with the director’s oeuvre. It’s a genuinely fascinating movie which subverts all that has come before. Ceylan’s films have always been free-flowing poetry with a confessional element. Like so many great directors before him — Noah Baumbach, Albert Brooks, or Alice Diop — they process their own foibles with characters who strongly resemble themselves, exploring the complexities and difficulties of personal relationships.

In 2006’s Climates, Ceylan wrote, directed and starred alongside his real-life wife, portraying a toxic relationship on the brink of dissolution, showcasing inadequacies that feel deeply personal. Even his most mainstream film, the crime drama Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, dives deep into the limitations of its central characters, with the supposed criminals overly concerned with their own bravado and love of a drink to pull off what could otherwise be the perfect crime. It’s an intoxicating blend of hubris and humility that makes for deeply satisfying cinema about men who overestimate their genius.

Much like Swedish director Ingmar Bergman and Soviet filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, who Ceylan regularly cites as an inspiration, his films are deeply personal, dreamy and meandering. His third feature, Distant (2002), brought him to Cannes for the first time and won him the Grand Prix for its portrayal of depressed cousins alone in a small Istanbul flat. Ceylan continues exploring those feelings of being spiritually and emotionally alienated throughout his filmography, telling the Hollywood Reporter earlier this year: “Though my films are rooted in some political and social realities of Turkey to some extent, I hope they rather try to explore themes of existentialism, alienation and the human condition to create a sense of introspection and philosophical inquiry.”

In his Palme d’Or winner Winter Sleep (2014), another sweeping three-and-a-half hours of pure poetry inspired by the works of Chekhov, the characters are just as dejected, as dispossessed, as in his other films. Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), a former academic and actor, is convinced he understands the struggles of ordinary people despite his immense privilege. While in many ways this character shares a DNA with the main protagonist in About Dry Grasses, Aydin has more redeeming qualities than Samet, who is more cruel and angry than just oblivious. Samet possesses nihilism and a lack of curiosity about the lives around him, which seems at odds with Ceylan’s previous work. Still, the director has spoken about a desire to continuously evolve in his more than three decades of filmmaking, telling Cineuropa last year that part of his approach is “just experimenting with different things”.

Ceylan’s work may be perplexing at times, and the lengthy runtimes certainly aren’t for everyone, but they are all enriching pieces of cinema that find beauty in the most desolate of places. About Dry Grasses is no exception. Even if Samet is irredeemable, there is still heart of the film in the form of Nuray (whose similar name to the director feels like a nod to where his true sympathies lie). The film holds that the world can be harsh, unfeeling, and filled with the casual cruelty of Samet’s classroom, but so long as we have Nuray, we leave About Dry Grasses as we do all of Ceylan’s films, with a glimmer of hope.

About Dry Grasses is in UK cinemas from 26 July.

Newsletter

Newsletter