I was raised to believe family is everything — but a communal life is almost impossible to lead

My Sudanese heritage says I should take care of my mother and my elders. But I feel something akin to guilt about choosing to live thousands of miles away from those who raised me

Earlier this month, I greeted my mother for the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic. Separated by the vast distance between the UK and Australia, it had been more than four years since I’d last seen her in person, laid eyes on her mischievous smile and squeezed her small frame tight, towering over her in the way I had since I was 12. As we embraced under a wet London sky, my senses were flooded with waves of competing emotions.

The first was cool relief at seeing her in good health and high spirits, Alhamdulillah. Our parents may be practised in the art of concealing their pain, but little escapes the keen eye of a first-born daughter (I cannot speak for other siblings) and I was glad to see her joie de vivre rang true.

Relief was followed by the gentle sting of surprise, as I realised the memory of my mother no longer matched the reality. In my mind’s eye, my mother is permanently young, but the woman I held in my arms was older, perhaps even more fragile — though she would be horrified to hear me say this. Time had revealed its swift, unceasing passage in the mellowing of her gaze, the softening of her skin. A prickle of slight trepidation also made itself known, the familiar nervousness many adult children experience while hosting older parents, faced with the adult/child dynamic that seems to never wholly disappear.

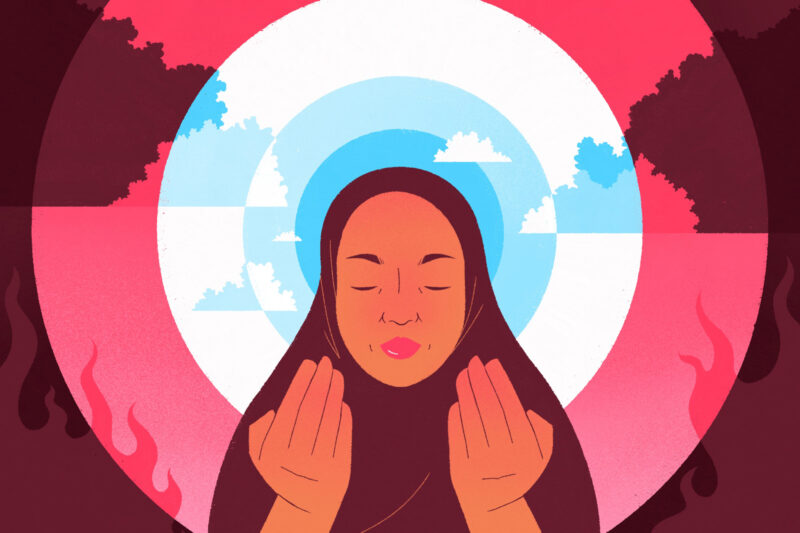

Mixed in with the gratitude and sense of long-awaited reunification was something else, a feeling altogether more complicated, the texture of which I find difficult to name. Not quite guilt, but perhaps her cousin. A sense that there was something off in the way I had chosen to live my life, thousands of miles away from those who raised me. A quiet sadness that although I had done in my 20s what my parents had done in theirs — migrate with nothing but two suitcases and one’s savings — somehow this was not how things “should” be, that this was not the way we, as Sudanese, as Muslims, were meant to be living.

That was after all, the story I grew up with. We’re a communal people, my brother and I were told. Family is everything. Your elders, your cousins, your parents, these are your kin: who you depend on, who you look after, who look after you. It seems strange to look back and realise that while that was the story, we actually grew up in a different reality.

Family was everything, but only in theory. We were first-generation migrants, after all. Before the advent of Skype and WhatsApp, my parents could afford to speak to theirs on the phone only once a month, if that. We took care of each other as Sudanese were meant to, but from afar. The only time we spent with our relatives was during the biennial summer stays back in Sudan, a concentrated block of time where we did our best to develop the relationships we were told were the most important.

As I greeted my mother for the first time in almost half a decade, it struck me that our relationship was not the aberration that I had made it out to be but, in fact, mirrored that of hers and her own mother. She did not see her mother for years at a time, raised her children in “foreign lands”, educated her offspring in an unfamiliar tongue. It makes sense, then, that that is what I would do. Whether consciously or unconsciously, I repeated the pattern that I saw, the pattern that in my house was “normal”. Move away to a foreign land, build a life somewhere new.

But this was never meant to be the story. There is a part of me that still wonders if my “proper” role in life is to live in a family home with my elders and youngers, my parents as the respected elders surrounded by loved ones and tolerated ones, in the same way my grandparents were in the manner of generations of Sudanese before us.

There is a part of me that believes my parents would be happiest in that scenario — certainly my father would be, his role in the family clear and valued in a way Anglo societies do not understand. On my worst days, I wonder if it is my fault, if it’s my choices that prevent that reality from existing. Perhaps if I were a better daughter, all their dreams would come true.

But we are so far from that dream existing, and I don’t know if anything has, or can, replace it. For even if I could make different choices, like so many fellow Sudanese, the family homes that we may have hoped to grow old in have been destroyed in the war, either occupied and raided or completely levelled by armed forces. Collectively, we have suffered an interminable loss, but how do you begin to grieve an entire way of being, before the weapons have even been lowered?

The truth is, the lives we were told were our birthright — the communal, kin-based life — are almost impossible for us to lead. As first-generation migrants, as twice migrants, and now, as Sudanese. How do we reconcile that gap?

This is no blame game, no one at fault. There is only acceptance, and the space to imagine something new, because that is all we have been left with.

I lead my mother on a tour of London, and wonder how I will take care of her from thousands of miles away. I wish it were different, while understanding it may never be. All we have are choices within an impossible reality, and we are doing the best we can. Alhamdulillah.

Newsletter

Newsletter