Remembering summers in Marmaris and the vibrancy of Turkish food

For writer Carla Kay, annual visits to see relatives in Turkey have helped her bond with her culture and navigate her life in New York

The body of an immigrant longs for comfort. In the United States, where the inundation of difference and stimulation can be dizzying, this longing becomes an instrument, transposing sounds of home into new settings.

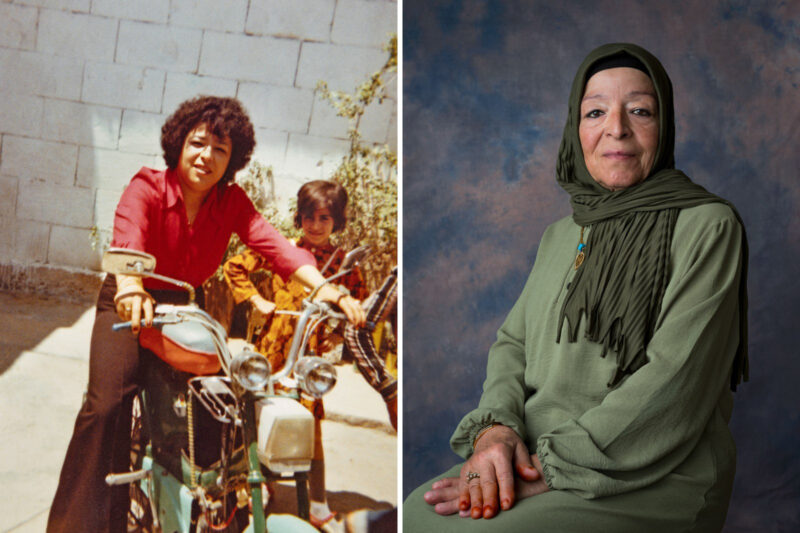

I know this is the case at least for my mother, who emigrated from Turkey to the US in 1995 to join my father and raise her children. My mom returns to Turkey at every chance she gets to be with her family, to speak her language, to practise her cultural values, and, importantly, to eat her food. Often, when I phone Turkey, she will be at the table with our family, eating the ev yemek (home food) that she, and subsequently my sister and I, grew up on.

During these calls, I feel my mom at ease, and it puts me at ease. The vibrancy of Turkish culture, brightest at the dinner table, is palpable as I sit alone in my small New York City kitchen. I hear my anneanne (grandmother) muttering to herself as she stuffs grains of rice into green bell peppers before setting them to cook slowly on the stove. I smell onions frying and the underlying aroma of fresh parsley; the smooth olive oil in every dish coats my mouth and flows through my body.

The longing to be there with my family, to eat, is visceral. This is a generational longing, passed through my mom’s body into mine from the beginning of my life in her womb. As I’ve grown up, my mother has shared with me memories of the foods of her culture and homeland, exposing me to a past that while I cannot live, I can taste.

My mom and her cousins grew up in restaurants. Many of them were raised in the outskirts of big cities such as Ankara and Istanbul. The children of my mother’s generation returned every summer to Marmaris, a small city touching both the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas, carved by coves and protected by hills of dry pine trees that leak world-renowned honey.

As the oral histories go, back in the 1980s the cousins would be sent from the hot and crowded cities to Marmaris, where they would help my büyük dede, their grandfather, run his business. His seaside restaurant served well-made traditional dishes, mezze, and local seafood to Marmaris natives and summer visitors escaping surrounding cities.

I imagine Marmaris in those days to be quite untouched, left to flourish as a small seaport with naked Turkish children running over rocky beaches and overgrown trees drooping with the weight of juicy pomegranates. My mom tells me that she served tea to some of the first German vacationers to arrive in Marmaris.

Today, the city is flooded with tourists and packed with resorts and water slides. This cultural shift makes me long for a past that I never lived, but wholly feel when biting into my anneanne’s lahmacun, with its deeply savoury layer of ground lamb soaked in lemon and wrapped around a bunch of tender parsley, spicy red onions, and sweet, juicy tomatoes.

We continue the tradition of returning to Marmaris every summer to maintain a piece of family history despite the forces that have attempted to erase it. Our best summers gather up to 30 family members crammed around plastic tables on steamy balconies. Cigarette smoke and complaints about current politics are the soundtracks to these gatherings, along with the wails of whichever new baby has popped out that year. While the grouping might change depending on the night or who has spent the longest time cooking, it is often my own anneanne that we gather around, as she is undisputedly the best cook. She hails from Gaziantep, widely regarded as Turkey’s culinary capital. I wear this family history with pride and will often introduce myself to other Turks as Antepli to come off a bit…spicy.

I remember nightly dinners in Marmaris as some of my happiest and most comfortable moments. These memories are personal and intimate, arousing sentiments that no one other than me can experience. So, when I try to communicate my Marmaris to others, I choose a different image, one with vivid colours and exquisite flavours, in the hope that my listener will be able to taste it themselves.

At some point during our family convening in Marmaris, lazy dozes on the hot porch and short walks to the local fırın (bakery) turn into restlessness, and we head to the water. Every family pitches in and we take a boat out into the sea; we have no destination in mind and no appointments to get back to. Our sun-browned, sticky bodies flake with pure sea salt that dries on the skin as soon as we climb out of the water. The boat is owned by an old Turkish fisherman-turned-captain who exchanges genial words with us but remains in his own world for the most part, a world shaped over years on his familiar waters. He grew up in Marmaris, washing decks and slinging ropes until he made it to the top. It is he as our captain who will decide the route that we take, and he as our host who will decide the meal that we eat.

After the sun has reached its peak and the children have been tired out by the first few hours of deep dives into the clear blue waters, our captain starts to cook. It is unannounced; he has been quietly observing and now senses that we are ready. He prepares simple meals with nothing but a cutting board, a knife and a small grill.

As always, parsley, lemon, tomatoes, and sliced red onion, the foundational ingredients of Turkish cuisine, are in abundance. Black olives glisten in the sun, and we suck off their flesh and spit out the pits. (I have been known to eat the olives of an entire dinner table on my own before anyone notices). Hunks of briny white cheese wait to be scooped up with fresh, fluffy, sesame-crusted pide, gathered from a seaside baker who has been providing for the boat workers for as long as they have been there to provide for.

A modest salad consists of Turkish bell peppers, tomatoes, cucumbers, and green onion dressed with dark Turkish olive oil, lemon, sumac, and pomegranate molasses. The trick with this salad is to season with salt and wait. Prepare it first, and by the time the rest of the meal is ready the salty vegetable juices will have swallowed the aroma of the green onion, the bitter sweetness of the molasses, the bright acidity of the lemon and the herbaceous, almost creamy olive oil into what I call kaplan sütü (tiger’s milk). Kaplan sütü is my Turkish take on leche de tigre, which is the mouth-watering pool of flavour that is left at the end of a ceviche. It is the elixir of our culture, and at the end of our meal we’ll pass it around the boat, each taking a few sips to cleanse our palates and reinvigorate us for the rest of the day. One day, this dish will feature on the menu of my own seaside restaurant. A girl can dream.

These opening acts, harmoniously whetting our appetites, set the stage for the star of the show. Our captain leans over the edge of the boat and with a grand sweep plucks a fish from the salty sparkling sea below us. Live action meal prep happens before our eyes as we float on the Mediterranean, roasting in the sun surrounded by our loved ones.

The fish, a fat and glimmering sea bass, is thrown on to the grill and cooked to perfection. As soon as it hits the table, its tender meat is forked into flaky chunks off the bones and drizzled with olive oil and a heavy pour of sizzling butter. The only seasoning this fish asks for is barely a sprinkle of salt and a few hearty squeezes of lemon and, in the blink of an eye, we have our meal. It is a work of magic, a spell cast upon us drifting diners. The meal is divine, relished under the hot sun before we slip into sweaty naps or back into the water. Paradise, no?

Food, memories of it, and dreams of it, tie me to my family and to my culture and dictate the way I continue to navigate the world. Growing up literally metabolising nutrients and flavours, I have at the same time metabolised the stories and sentiments that come with them.

In Marmaris, sharing meals at sea with my family, I can taste my mother’s childhood summers. The comfort I feel, and the longing for a past I’ve only heard stories of, remain in my body when I return home to America. Here, my mom will continue to search for the comfort of home by attempting to replicate my anneanne’s lahmacun; she’ll find fellow immigrant Turks to speak her language, to practise her cultural values, and to eat her food with. Returning from Turkey, she’ll discover her suitcase packed with hidden gifts sent secretly from my anneanne to me and my sister: molasses-covered walnuts, pickled peppers, the family’s yoghurt starter and a jar of Marmaris honey.

It is through food that my anneanne chooses to communicate with us across the ocean as she knows that it is food that comforts us. For my mother, these tokens will briefly quench her longing, reminding her that she and her daughters are unwaveringly tied to home. Sharing these gifts around the table in our New York City kitchen, we are transported back to Marmaris, to the sun and the salt and the life-giving kaplan sütü.

Food has the power to mediate time and space. Today, I manipulate this power to communicate with the world around me and to create new memories around tables. I feel pulled by the flavours of Marmaris and my cravings well up inside me, so I try to transpose them in an act of catharsis. During my New York City summers, I gather friends and strangers around a picnic table to serve them dishes that I’ve drawn from memory and adjusted with my own experiences, those that exist in a separate world from paradise in Marmaris.

We have no sea for us to escape the heat into, but the food and the music and the laughter (and the beer) make us forget. Whatever the meal I’ve created, parsley, lemon, tomatoes, and sliced red onion will be in abundance, piled at the centre of the table for everyone to reach. I’ll drizzle my Marmaris honey over peaches from the Turkish market and follow my grandmother’s recipe for dolma to dip into the yoghurt I’ve made from our family starter. My kaplan sütü includes feta and mint and chillis. Bowls of olives and some for their pits sit at every corner of the table. Pomegranate molasses sticks to our tongues and brings us together to a time and place that while we cannot live, we can taste.

This short story appears in Tales from the Kitchen, a new collection of food stories and essays about life and cooking, published by Fox & Windmill.

Newsletter

Newsletter