‘Where are the artists?’: Muslim creatives call for greater representation in the arts

Research into the UK culture workforce found widespread inequality across the creative industries

In her 20-year career as a visual artist, Zarah Hussain has never been commissioned by or worked with a curator at a senior level in the UK who is also Muslim. “Where are the role models in the arts? Where are the musicians and the artists?”

The lack of Muslims in the creative sector is a reality that’s been addressed in research published this year. In May, a Creative Policy and Evidence Centre (Creative PEC) State of the Nations Report found that the UK’s arts, culture and heritage workforce still has a long way to go towards inclusion. Using 2021 census data from England, Wales and Northern Ireland (Scotland’s data from its 2022 census is not yet available), and from the Labour Force Survey, the report found that 20% of workers in the creative industries are disabled. As many as 90% of workers are white, while 60% are middle class. A deeper dig into the data indicates industry-specific problems of inclusion and diversity. For example, in film, TV, video, radio and photography, less than 9% of people are from a working-class background.

While headlines focused on race and class, one new notable finding was neglected by media coverage: the report’s analysis of religious affiliations. Previous census data has been limited on religion and faith, and this is the first major report to highlight the representation of Muslims in arts, culture and heritage occupations. The results were not encouraging. Other than as authors, writers and translators, the report found that Muslims are “particularly poorly represented” across creative industries and jobs which include dance, music, visual art, acting and managerial positions. Hindus were also poorly represented, and the largest representation in the arts, culture and heritage workforce was, in fact, “no religion”. For example, there were 500 Muslim musicians listed in the census compared to the 27,300 musicians who did not identify as religious.

“I wasn’t surprised by any of this,” says Dr Mark Taylor, a senior lecturer in quantitative methods at Sheffield University and a co-author of the report. “These numbers have basically been the same for as long as it’s been possible to measure them. The sort of changes that people might expect to have seen over the last decade or so just really haven’t happened.”

“Am I surprised we’re underrepresented? No,” says Lamisa Khan, one of the founders of Muslim Sisterhood. “Muslims make up the poorest demographic in the UK,” she says, acknowledging that 39% of Muslims are living in the most deprived areas of England and Wales. “When you think about creative work, until you make it, it’s not financially lucrative. And when we come from second-generation, first-generation immigrant backgrounds, a lot of the time we’re most likely to pursue careers that are financially stable and be encouraged to do that because those are the industries you see yourself reflected and successful in.”

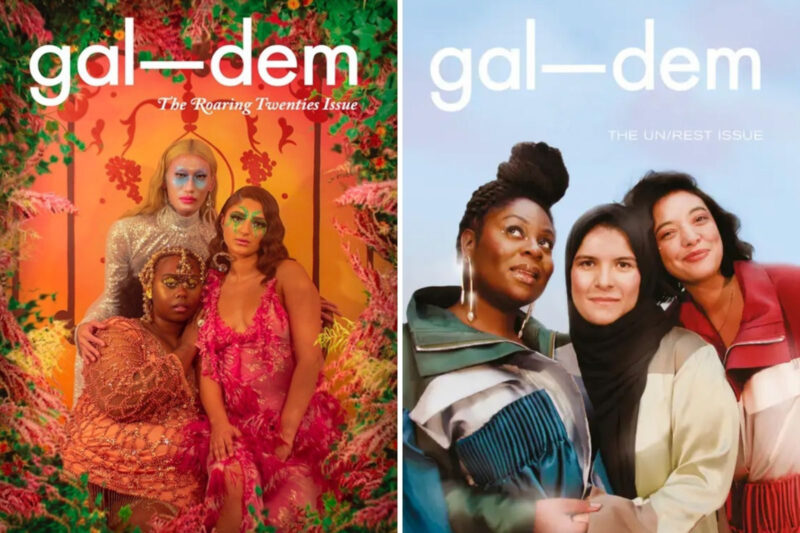

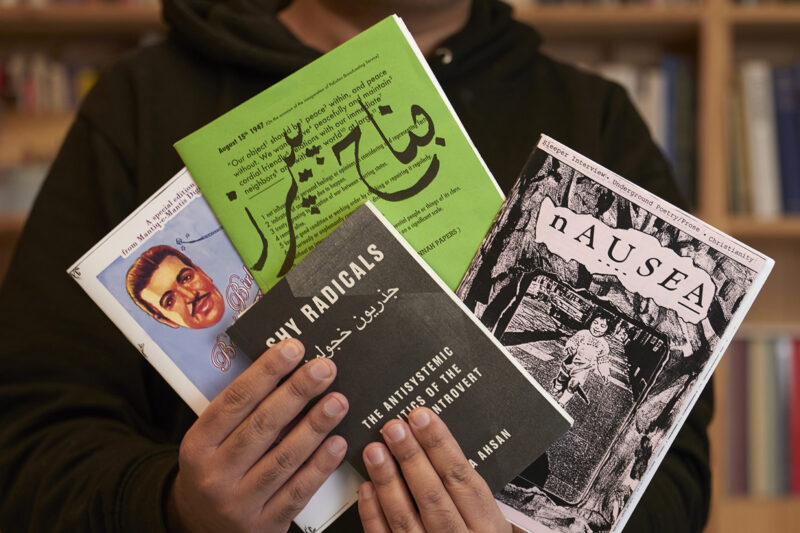

Muslim Sisterhood was founded in 2017 by Khan, and artists Sara Gulamali and Zeinab Saleh. Originally it was a DIY photography project on Instagram, highlighting young Muslim women, before evolving to also include community events and self-publishing. “Everything is done by Muslim women,” says Khan. “From the graphic design to the make-up, to the writing.”

Now, Muslim Sisterhood is an international creative agency, working with brands to improve the representation of Muslim women in front of and behind the camera. “We work with female crews and prioritise Muslims and people of colour,” explains Khan. “We want to create access to opportunities and make sure those behind the camera are reflective of those in front of it, to ensure we’re creating authentic representation and it’s not coming from a white gaze.” Income from the creative agency is used to fund Muslim Sisterhood’s free workshops and community events. “Our primary focus is on community building and creating opportunities for young Muslim women.”

Financial instability within the creative industries is also one of the reasons why Hussain thinks Muslims are poorly represented in her field of visual arts. Another intersecting reason is a lack of role models and mentors for early-career Muslims in the creative sector. “Can you name more than five Muslims? I couldn’t name five people who are nationally well known,” she says. “Historically ethnic minorities have gone into professions like medicine, law or accountancy because they offer stability, security, higher wages, respect and a pathway. If you go to your local hospital you’ll come across loads of senior doctors, consultants and heads of departments who are Muslim.”

Like Taylor and Khan, Hussain is not shocked by the Creative PEC report finding that Muslims are poorly represented in most creative industries. But while the report might not be surprising, it is important evidence of what many Muslims in the sector have been saying for years. In their analysis, the report’s authors drew upon the research of Dr Saskia Warren, a senior lecturer in human geography at the University of Manchester, who interviewed more than 120 Muslim women creatives for her book British Muslim Women in the Cultural and Creative Industries. “There might be the view that if you don’t have the data, then there’s no problem,” explains Warren. “In fact it can be the opposite. It can be that there’s a blindspot and it can mean that there’s no data to argue with in order to address issues.”

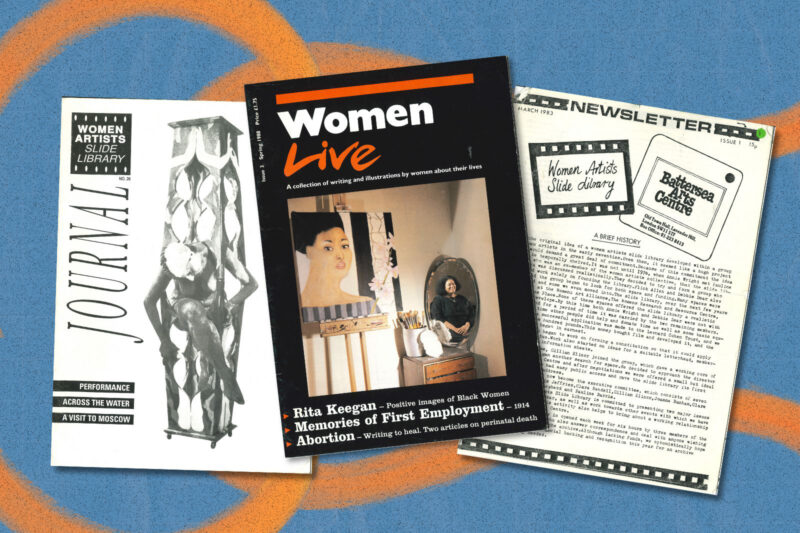

In her research, Warren has argued that religion is often a missing index of inequality in the arts. “Many arts and cultural institutions want to engage more with areas that had high levels of Muslim populations but they are too tentative to directly discuss religion.” Instead, Warren points out, organisations will use proxies like race or region. “But there’s something lost in translation there. It doesn’t enable more nuanced discussion around minorities from different heritage communities. What I saw in digital media, fashion and visual arts was a growth of women who were using identity markers really positively and who were framing faith and being Muslim as central to their creative identity: reworking, contesting, challenging ideas of what it meant to be a Muslim woman through their artwork.”

Both Khan and Hussain speak to a lack of understanding or consideration for Muslims within the creative industries. “There’s the barriers of unsociable hours and working around alcohol,” notes Hussain.

“I found it really difficult to navigate the creative industry,” says Khan about her early career. “There were a lot of drugs, alcohol, partying and there was a point where I was like: ‘I can’t do this anymore because I’m struggling to justify to myself and my family why I’m doing the work that I’m doing because it’s at the cost of my being’.” Warren also points out that the association of the creative industry with an intense alcohol culture is a reason why some Muslim parents might not want to send their children to art schools.

But Hussain suggests that the biggest barrier to Muslims entering the creative industries is not just a Muslim issue, but rather a sector-wide problem. “It’s economics,” she says. “The talent is there. The desires are there. But if you say to a young person: ‘You’re going to be poor for the rest of your life’, it’s not a choice many people want to take. There are very few people who come out of college and jump into the world of art and start making money. It takes a long time to incubate and find success. If you don’t have financial means or parents who will support you, it’s an impossible dream. It was difficult when I graduated in 2004, but it’s more difficult now.”

Government support is also lacking for the creative sectors, at both local and national levels. Research commissioned by actors union Equity this year found that arts funding for the UK from national bodies — the Arts Council England, Arts Council of Northern Ireland, Arts Council of Wales and Creative Scotland — has been cut by 16% since 2017. Whether funding for the arts improves under the new Labour government remains to be seen.

With the Creative PEC report highlighting that the UK’s arts sector is still overwhelmingly middle class and white, accessible ways into creative industries are more important than ever. It’s why Muslim Sisterhood is still pushing to create more opportunities for their community. “At Muslim Sisterhood I’m surrounded by incredibly talented beautiful Muslim women who are leaders in their craft and meticulous in what they do,” says Khan. “I’m so disappointed they are not given the opportunities they are deserving of.”

The under-representation of Muslims in arts, culture and heritage does not just impact Muslim communities. It’s a loss for British society at-large. As Khan says, without Muslims: “You’re losing so much storytelling and richness in culture, food, heritage”.

“Art is an insight into other people’s lives,” says Hussain. “Art engenders empathy towards and understanding of other people and cultures, and when you lose that you lose something really key.”

Newsletter

Newsletter