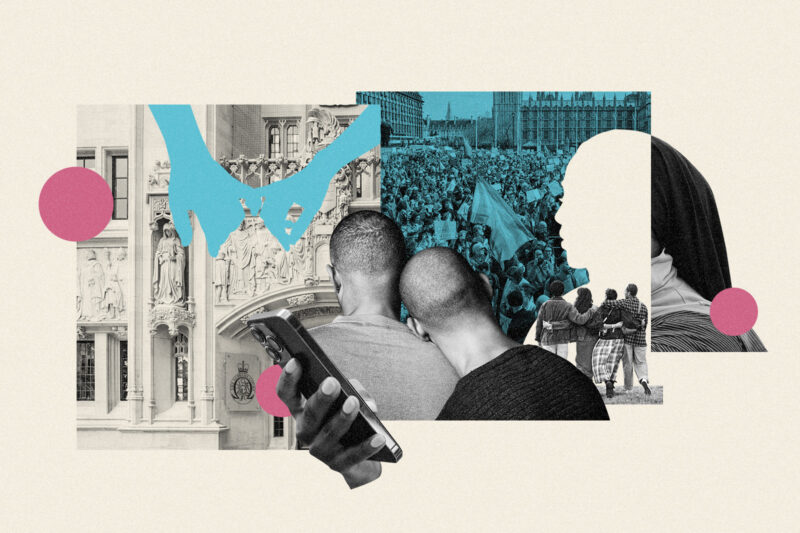

Councils are turning off street lights to save money, but what does that mean for women’s safety?

Cash-strapped councils in England and Wales are reducing street lighting at night, sparking criticism from safety campaigners

When Atiya Zakaria heard that more councils across England and Wales are planning to turn off street lights at night as part of cost-cutting measures, she was shocked. The 25-year-old lives in Southwark — a south London borough that tried to save cash back in 2010 by turning off the lights for a few hours at night. Having worked in a local community centre for the past 18 months, she’s seen first-hand how the lack of street lighting, combined with more visible drug use on the streets, has made women and girls feel increasingly unsafe in public spaces after dark.

“It took me by surprise that it was even being considered by councils,” says Zakaria, a community worker at Oasis Hub in Waterloo, part of the new Safe Havens network launched last year as part of a partnership between Lambeth and Southwark councils to tackle violence against women and girls.

“My mum wears a niqab, so growing up we always had problems with comments,” Zakaria says. “I don’t think I would feel at all comfortable going out in the evening if it’s not lit up.”

For more than a decade, cash-strapped councils in England and Wales have pursued cost-cutting measures such as reducing street lighting, sparking criticism from groups dealing with women and minority groups’ safety. A 2015 review from the Royal College of Policing found crime had reduced by 21% in areas where street lighting was increased.

Yet in the past year, Norfolk, Croydon, Cornwall, Havering and Hampshire councils have announced plans to dim lights in an effort to save money and increase energy efficiency. In May, Coventry council launched its “part-night lighting” scheme, in which around 70% of the city’s lights will be switched off between midnight and 5.30am during weekdays, and from 1am on the weekend, which it says will save £700,000 a year.

The recent cost of living crisis and energy price increases, on top of years of austerity, have decimated council budgets and local services across the UK. Councils’ overall core funding per person fell by an average of 26% in real terms during the 2010s, with higher council tax revenues only partially offsetting a 46% fall in funding from central government. It’s communities that bear the brunt of the cuts: two-thirds of English local authorities are planning severe reductions to neighbourhood services this year, according to the Local Government Association (LGA).

The LGA told Hyphen that long-term funding is needed from the new government to give councils the “best chance” to tackle problems such as public safety, and invest in preventative strategies.

“Community safety is a top priority for local authorities,” an LGA spokesperson says. “Despite funding pressures, including significant increases in energy costs, councils continue to spend and invest heavily in street lighting, including in upgraded, environmentally friendly lighting which costs less to run.”

Jim McMahon, newly appointed minister of state at the Department for Levelling Up (DLUHC), Housing and Communities, acknowledged the priority of addressing the financial crisis among councils. “Councils have their financial arrangements for the rest of the year already, we’re preparing the ground for December. We’re committed to ensuring that councils have the resources they need to provide decent public services to their communities,” he said.

“Fixing the wider system is really important, because in the end, a lot of pressure that’s brought to councils is because they’re the last line of defence. But it’s a whole system that needs to be repaired.”

But campaigners point out that there is a fine line between economic responsibility and community safety.

“Harassment happens everywhere,” says Charlotte Keely from Our Streets Now, a campaign demanding the right of women, girls and marginalised genders to be safe in public spaces. “These issues are built from cultures of inequality, and those cultures of inequality look different depending on who you are, your background, your identity.”

Southall Black Sisters, an organisation supporting women of colour who have experienced gender-related violence, warns that it is minority communities who are most at risk.

“More than a decade of austerity has negatively impacted women’s safety,” a spokesperson says. “Black, minority and migrant women experience these impacts disproportionately and their vulnerability is heightened due to their position at the intersection of race, class, immigration status, religion and disability.”

Indeed, the decision to turn off street lights is particularly concerning in the context of a sharp rise in anti-Muslim hate crimes since 7 October, campaigners say. In the four months following the Hamas attacks on Israel and the subsequent bombardment of Gaza, Tell Mama, an organisation that documents Islamophobia and anti-Muslim attacks across the UK, recorded more than 2,000 incidents, the largest recorded number in the same timeframe since the organisation was founded in 2011, and a 335% increase compared with the same timescale in the previous year. In more than 65% of those incidents, women were targeted.

“Muslim women have an extra layer of vulnerability,” says Iman Atta, director of Tell Mama.

She notes that attackers often use visible markers such as a headscarf, skin colour, speaking a different language, or having an accent to choose targets they perceive as Muslim for Islamophobic attacks.

She adds that in the aftermath of the murders in 2021 of Sabina Nessa and Sarah Everard, there was “a period of time some women were not going down streets on their own, let alone ones that were badly lit”.

Organisations such as Southall Black Sisters are calling for a commitment from the new Labour government to end austerity and adequately fund local services, so councils don’t have to resort to such measures as turning off street lighting. “Public services need to recognise preventing and ending violence against women and girls as a strategic priority, and embed this across all areas of decision-making,” their spokesperson says.

Indeed, Keely adds that only addressing street lighting “is not actually solving the problem where it stems from. There’s a myth that violence only happens in dark alleyways, or at night, or when you can’t see it happening, whereas actually violence happens when people are watching and don’t stand in, or don’t speak up.”

The issue is systemic, she says: “We can see the problems with misogyny and racism and Islamophobia within policing, so if we want to create systems where people feel like they put trust in those institutions when things do happen, that feels like step one.”

A spokesperson from the DLUHC pointed to the new government’s mission to halve violence against women and girls in a decade, and highlighted that they will ask the police to relentlessly pursue perpetrators who threaten women’s safety.

Newsletter

Newsletter