Marwan Kaabour Q&A: ‘Slang fills in the blanks where conventional words aren’t able to express something’

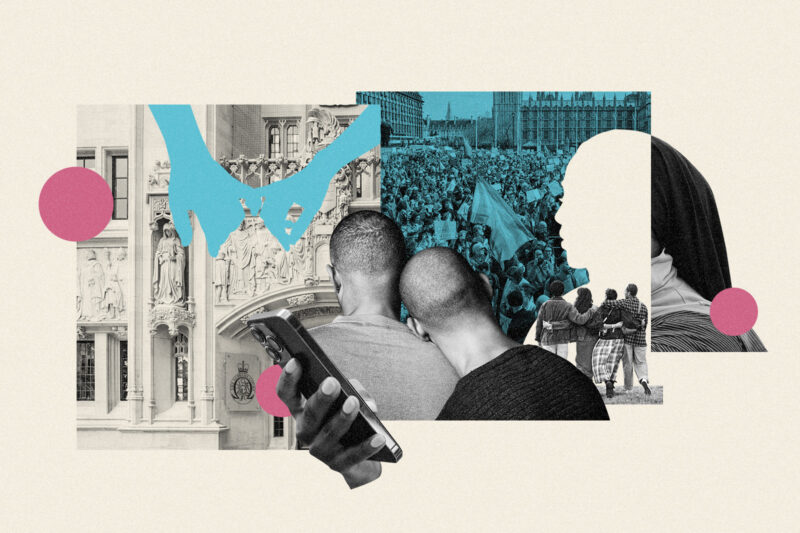

Marwan Kaabour’s debut book, The Queer Arab Glossary, is a crowd-sourced catalogue of more than 350 slang words used by LGBTQ+ people across the Arab world. Photo courtesy of Marwan Kaabour

The visual artist speaks about his debut book, a glossary of LGBTQ+ slang in the Arab world

Marwan Kaabour, 37, is a graphic designer and visual artist whose work responds to gender, sexuality and politics. Kaabour was born and raised in Beirut, Lebanon, and settled in London after completing a master’s in graphic design at the London College of Communication.

In 2012, he began working for Barnbook Studios, a design firm focused on social and political causes, where he produced a visual autobiography for the Grammy award-winning singer Rihanna.

Kaabour set up an independent practice in 2020, as well as a popular Instagram page, Takweer, which documents queer culture in the Middle East and North Africa. His debut book, The Queer Arab Glossary, a catalogue of more than 350 crowd-sourced slang words used by LGBTQ+ people across the Arab world, was published in June.

He spoke to Hyphen about the importance of slang and queer identity in Arab communities.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did the book come about?

I asked my Instagram followers: what are the words and terms in Arabic that they use to refer to each other or to queer people?

Because even though there are two billion Arabic speakers in the world, we speak many different dialects that vary massively. As a Lebanese person, I am familiar with the dialects of Lebanon and the neighbouring countries. But the further away you get, the more alien the dialects become, especially when we’re talking about slang, and when it comes to queerness it varies massively.

I got a lot of messages from people belonging to different parts of the Arab world, and they would always use words that I wasn’t familiar with. So I started to get curious and wanted to create a linguistic mapping of queerness in the Arab world.

What were you surprised to learn in your research of this book?

The Arabic language is known to be very poetic, and it’s interesting how it is used in a good and bad way, as in a derogatory and an endearing way, to draw these fantastical scenarios about the bodies, the sex lives and the identities of queer people. It was talking to people from different backgrounds from that region of the world that really opened my eyes to how much slang could tell us about how we view a certain subject matter, because slang fills in the blanks where conventional words aren’t able to express something.

How did you approach presenting some derogatory and offensive terms in your book?

I would argue that the majority of the words in the book could be categorised as pejorative. But a lot of these words vary depending on who uses them, how they are used, the tone in which they are used, and the context in which they are used. By eliminating words that are negative, we also remove half of the story. It’s a hurtful part of the story, but it’s an important one.

You found that there aren’t many words to refer to LGBTQ+ Arab women – slang or otherwise. How did you work around this gap in vocabulary?

Even when speaking with queer women, they wouldn’t have many words to tell me about. They would actually tell me more about what words the boys use. It has to do a lot with our inability to take women’s sexuality in the same degree of seriousness that we take that of men’s. We only speak about queer women as women who are trying to imitate men.

I realised that not only is there a huge gap in vocabulary around queer women, whenever they existed, they existed within the patriarchal approach. There is a very common word that is used in the Gulf region: boya, which is the Arabisation and feminisation of the word “boy”. You have lots of different variations of “tomboy” in every country. The most direct answer to this gap is Rana Issa’s essay in the book whereby Rana imagines a fictitious, morning coffee gathering between a group of real and fictional women, trans women, trans men and non-binary people from Arab history, where they sit around and talk about their sex lives, their bodies, and even coin new words for things.

What imagery did you use to visualise the words in the glossary?

I wanted to not only create words, but to create images. A lot of these words, as you mentioned, are derogatory and hurtful to people. But what if we create, or we almost mythologise these words into these fantastical creatures or queer deities of sorts, and infuse them with a lot of joy and dark humour with a tongue-in-cheek approach, almost to have young queer kids look at them as a source of comfort rather than a source of fear or shame?

Can you tell us about any future projects?

I’m producing a number of books for very exciting cultural institutions: the Hayward Gallery, and I’m working with the Tate next year. But when it comes to my own personal practice I’m simply curious to see where the journey into this book will take me, as I’m sure it will generate discussions that will make me want to follow creative threads I’m not aware of just yet.

The Queer Arab Glossary by Marwan Kaabour is published by Saqi Books and is available now.

Newsletter

Newsletter