‘We’ve become a borough that’s resilient’

With a chronic housing shortage and the UK’s highest rate of child poverty, Tower Hamlets relies on hundreds of community groups, in keeping with its long history of activism

Aisha’s* belongings are packed away in plastic bags and overflowing boxes. Black mould has spread around her house, eating away at walls, furniture, carpets and appliances costing thousands of pounds.

Despite three years of leaks and dozens of complaints to her social housing landlord, the mould covers entire walls in the two-bedroom Tower Hamlets flat where Aisha lives with her five children.

“I’m struggling here, with my children, and no one cares,” she said. “My younger son has been suffering with bad allergies, and he’s having difficulty breathing now. All of them are getting itchy patches over their skin. It’s not good for them to live like this.”

As I enter, Aisha introduces me to her eldest son. Last year, he finished his A-levels, achieving all A*s and As. He studied for the exams in a cramped and mouldy bedroom he shares with two siblings.

Despite the state of the property, overcrowding and the fact that Aisha’s ex-partner was recently convicted of domestic abuse, the local council and her landlord have yet to rehouse her or help her to apply for accommodation elsewhere.

I first came to Tower Hamlets to report on how the borough’s housing crisis was affecting the Somali community. At group meetings and on WhatsApp, I was told dozens of stories of parents forced to share a one-bedroom flat with up to seven children and community services pushed to the brink by an unprecedented scale of poverty and homelessness.

Despite being home to the financial powerhouse of Canary Wharf, Tower Hamlets is a place of extreme inequality and a Dickensian level of destitution. Nearly half of the borough’s children grow up in poverty, the highest rate in the country. Some of the worst hit are Muslims — a community that makes up 40% of Tower Hamlets’s 320,000 residents, the highest proportion of any local authority in the country.

For Aisha, over the past few weeks and months letters and calls from British Gas have poured in, demanding the immediate payment of energy bills worth £3,000. The bills amount to three months of the £12,000 Universal Credit she receives each year. Paying off the debt would leave the family penniless.

“I told them: ‘If I pay you how am I supposed to live?’,” she said.

Some might dismiss Aisha and her story as an aberration marking the sharpest end of the UK’s ongoing cost of living crisis. But in Tower Hamlets, tales like hers are common.

“Right now is the toughest time I’ve witnessed in well over 40 years,” said Abdi Hassan, the founder of Coffee Afrik, a community outreach and support organisation that runs services including homelessness outreach and employment programmes. “Some children that we support are wearing the same clothes three, four, sometimes five days in a row,” he added. “Some mothers are skipping dinner.”

According to Hassan, Coffee Afrik’s 19 staff handled 1,124 cases in April alone, spanning housing and mental health issues to a huge rise in drug use. The diversity of the borough’s problems reveals a truism about poverty — it’s about much more than money.

Residents in Tower Hamlets have the second-lowest life expectancy in London. High air pollution and health inequality mean children in the area have 5% less lung capacity than the average for children in the UK. The borough also has a fast-growing problem with synthetic drugs.

Hassan likes to call it a “polycrisis” — a tangle of different issues that play off and make each other worse.

One of the main drivers of the crisis in Tower Hamlets sees poor housing cause people to fall into poverty through skyrocketing costs, exacerbated by rampant disrepair and overcrowding. One in every 41 residents in the borough is homeless — one of the worst rates in the country — thanks to rents surging by nearly 20% a year on average. Further exacerbating the issue is the sometimes decades-long waiting list for social housing that’s now over 23,000.

It’s a crisis with an added pain for many families because the council had financial reserves of more than £500m at the start of last year.

The council has acted in a number of ways to address the scale of poverty, including funding half a dozen food stores that give a £20-30 weekly shop to local residents in exchange for a small membership fee.

The council also lists some 24 food banks in the borough on its website, not to mention the half a dozen or more I encountered not on that page — almost certainly the highest density of food poverty programmes in the UK.

The crisis has changed how charities and community groups operate in the area. The charity Muslim Aid once focused much of its work abroad, but in recent years it has increasingly found itself serving deprived communities in the UK, including those affected by the cost of living crisis.

“We’re based in Tower Hamlets, but when it came to actually seeing which borough needed us the most based on the poverty levels, it is Tower Hamlets,” explained Diana Alghoul, the communication and public relations manager for the charity.

The charity distributed thousands of iftar meals a week in conjunction with the East London Mosque during Ramadan this year. “The Muslim population in Tower Hamlets is excruciatingly underprivileged,” Alghoul added. “You have areas like Brick Lane that are going through a massive gentrification project which, combined with the cost of living crisis, increases prices exponentially for the local population.”.

Trying to understand why the current cost of living crisis and rising poverty rates are so acute in Tower Hamlets gets you a lot of different answers, depending on whom you ask. Some of the factors are national — like the two-child benefit cap on Universal Credit, which affects more than 1.5 million children nationwide, or the austerity cuts to vital local services, both policies that hit those most in-need the hardest. Others are more local — such as the area’s supercharged housing crisis.

Some of these issues are more acute for many of the borough’s most vulnerable Muslim residents, those who have recently emigrated to the UK or have language barriers. “People are often just starting out in their lives here,” said Rukeya Khan, the advice centre manager at Toynbee Hall, a charity that has been helping the borough’s poorest residents for 140 years. “You essentially have very little choice in terms of the jobs you can take or the housing you can access.”

Those issues are often inherited by later generations. The Muslim Council of Britain warned back in 2022 that the cycle of poverty and lack of opportunities was trapping generations of British Muslims in destitution. One 2022 study by Islamic Relief suggested the poverty rate for the UK’s Muslim population was three times that for the country at large with just two thirds of those living in the borough in work, one of the lowest rates in the capital.

The sheer amount of time institutions such as Toynbee Hall have been active in the borough speaks to how long poverty and slum housing have haunted this part of east London.

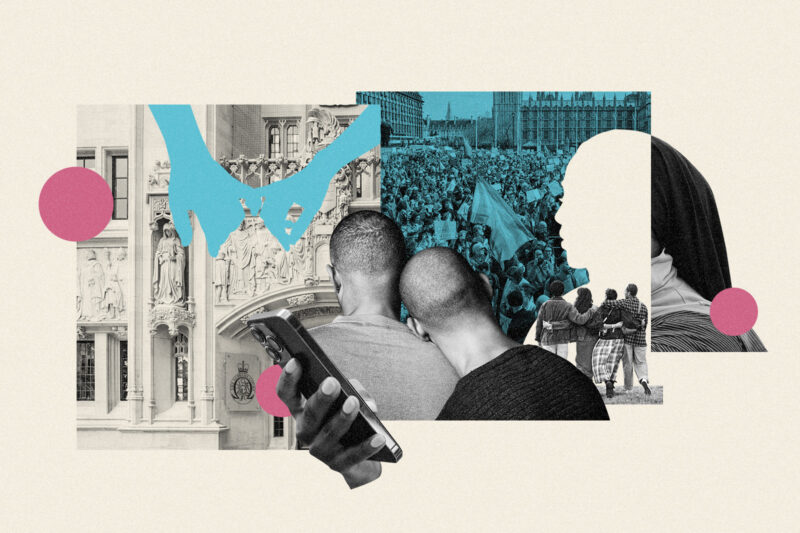

Tower Hamlets is home to hundreds of charities, community organisations and campaign groups. Service providers include trade unions such as the Independent Workers’ union of Great Britain, tenants rights groups such as the London Renters Union, community domestic violence charities, food banks and Somali community groups, to name just a handful.

This borough also has a long history of activism. In 1907, future prime minister and lawyer Clement Attlee moved to Tower Hamlets and it was during his stint working for local poverty charities that he changed from a Conservative to a committed Labour activist. Attlee was elected prime minister in 1945. That same year, Mile End was the last place in the UK to elect a Communist Party MP.

It’s not hard to see why the area has long attracted activist communities. In a city so heavily defined by the chasm between millionaire penthouse owners and those living in poverty below them, nowhere is that divide so materially evident than in Tower Hamlets, which is flanked in the east by the City of London and in the south by Canary Wharf. Many of the activists we spoke to said the two financial hubs felt like alien planets.

“There’s a glass bridge that separates our community from Canary Wharf. When it was built we called it the bridge to nowhere, because most people on this side of the bridge don’t ever go there,” said Sister Christine Frost, who helps run the Neighbours in Poplar community initiative and foodbank. “Poplar is the foothills of Canary Wharf, but we might as well be in Timbuktu.”

Speaking to the campaigners and residents of the area, I was told of heroin users camped near private members’ clubs, and homeless encampments laid out in the shadow of multi million-pound luxury apartments.

The radicalism born of the shared suffering and the scale of economic injustice mirrors the social values of the area’s residents. “Islam is a religion that is communal,” Alghoul explained. “There’s a verse in the Qur’an that says when someone saves one life, it’s as if they save the whole of humanity. Not the whole of the Islamic community, the whole of humanity full stop.”

The charity work of Muslim Aid and many of the other groups in the area is founded on Islamic ideals of justice and compassion, including zakat, the obligation that those Muslims who can afford it should donate 2.5% of their annual income to charity.

These principles are woven into an organising spirit that is perhaps stronger than anywhere else in the capital.

“There is so much that’s rich, that’s beautiful, that’s incredible about Tower Hamlets,” Coffee Afrik’s Abdi Hassan told me. “We have learned so much from our elders. You know, when you think about what happened on Cable Street, Altab Ali, the Somali Seafarers, we are a people that really understand how to organise, how to collectively liberate. We’ve become a borough that’s resilient.”

When I asked him if he thinks that community and its borough can weather the current storm, he seemed less certain. “I think something needs to fall for us to rebuild again,” he said.

Some names have been changed.

Newsletter

Newsletter