‘I had to eat my mother-in-law’s leftovers’: the hidden stories of in-law abuse

Some Muslim women experience years of exploitation at the hands of their parents-in-law. Now campaigners are calling for more awareness of the issue

–

Afsheen was 20 when she embarked upon a marriage arranged by an elder in her community in north-west London. When her future husband’s parents, who were local business owners, told Afsheen’s widowed mother they wanted the new bride to live with them, she accepted without hesitation.

“Things were different then,” Afsheen, now 38, says. “We didn’t really talk or get to know each other before marriage. My mum believed that we should always submit to the boy’s side.”

It was soon clear what Afsheen’s role as daughter-in-law and wife was to be. Once she and her husband were married, the family became controlling and she says she was a slave to his parents, forced to do tasks such as housework and cooking from dawn until midnight.

“His family wouldn’t let me leave the house. They chose what I wore and when I could wash,” says Afsheen, speaking under an assumed name as she still lives with the family. “I had to eat my mother-in-law’s leftovers from her plate because she said wasting food was haram. I wasn’t allowed a mobile and couldn’t go out. Anybody I knew was through them, so I was very lonely.”

Afsheen felt intense pressure to remain in what she describes as a “loveless marriage” and is now a carer for her mother-in-law, who is widowed and has dementia. She has realised she relies on Afsheen and the abuse has stopped, however she has never apologised or tried to make amends.

“I feel like my marriage is a life sentence,” she says. “I wish I had been strong enough to fight, but I was too scared of my mum, the community and my in-laws.”

Afsheen’s story is not uncommon in some conservative Muslim communities, where domestic abuse of women is carried out by parents-in-law. Pressures on women to conform to rigid gender roles can create fertile ground for exploitation and violence.

The spotlight fell on the issue of in-law abuse earlier this year with the case of Ambreen Fatima Sheikh, who moved from Pakistan to the UK in 2014 after an arranged marriage and was subjected to months of violence by her husband and his parents. During the family’s trial the court heard they were dissatisfied with the standard of her housework.

In 2015, Sheikh was doused with a corrosive substance and force-fed prescription medication, which caused catastrophic brain damage. Now 39, she has been in a vegetative state since and doctors believe she is unlikely to recover.

The Independent Office for Police Conduct has launched an investigation after it was revealed that West Yorkshire Police had conducted a welfare check on Sheikh a month before the attack, and reported her as appearing fit and well.

Sheikh’s husband, Asgar Sheikh, 31, along with his parents Khalid and Shabnam Sheikh, 55 and 52, were jailed for nearly eight years in February 2024.

Women’s safety organisations condemned the sentences as too lenient. Campaigners are calling for in-law abuse to be categorised as a form of “honour”-based violence — abuse carried out to defend the “honour” of a family or community.

“We recognise this case as one that is clearly underpinned by ‘honour’ and a vibrant young woman not meeting the expected norms of her husband and in-laws. Her story was completely avoidable,” says Afrah Qassim, CEO and founder of Savera UK, a charity working to end culturally specific abuse in the UK.

“While we are pleased that Ambreen’s abusers have been brought to justice, seven years is not sufficient for what she suffered. How many more cases do we need to see let down by the systems that should protect them, before the issue of honour-based abuse and harmful practices is given the attention and resources that it desperately needs?”

In 2022, Sajida Tasneem, a mother of three from Perth, Australia, was bludgeoned to death by her father-in-law during a trip to Pakistan. Back in 2012, a Birmingham man, Mohammed Tauseef Mumtaz, his parents and his brother-in-law were jailed for life for the murder of his pregnant 21-year-old wife, Naila, at the family home in 2009.

For every case that makes the headlines, many more women suffer in silence. Amina, a Glasgow-based organisation that helps Muslim and BAME women, told Hyphen that one third of around 3,000 calls made to its helpline annually are from women facing abuse from their in-laws. Callers detailed instances of physical and sexual violence, financial exploitation and domestic slavery.

In December 2023, Amina released results from research with 93 Muslim and minority ethnic women in Scotland. Many stated that their abuse involved their mother-in-law, and a large number were also abused by several relatives. Ninety per cent of women seeking help for abuse by parents-in-law said their husbands were also perpetrators.

The most common form of abuse reported to Amina is coercive control, widely defined as an act or pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation used to harm, punish or frighten victims. Owing to the very nature of such abuse, which often builds up gradually and normalises abusive behaviour, the organisation states that victims are frequently unaware that it is happening and, therefore, unable to report it.

Amina’s helpline staff have heard reports of women having their contraception confiscated by in-laws, with some saying control was even exerted over when the couple had sex.

Safa Yousaf, Amina’s violence against women and girls project co-ordinator, described the case of one woman whose movements were being monitored by cameras in every room in the house.

“She was only allowed in certain areas of the house at particular times and the fridge was kept locked,” Yousaf says. “We’ve seen very repressive and extreme controlling structures within the family.”

In some Muslim families, “invisible chains” of coercive control can start to take hold long before a marriage. Afsheen recalls her mother “drumming into” her the importance of respect for parents-in-law as a child. “For her, everything was geared towards preparing me for marriage and being the perfect daughter-in-law,” she says.

When Afsheen confided in her mother about the abuse she was experiencing at home, “she said if I divorced over such ‘minor issues’, it would bring shame on my family”.

The importance of family honour also plays a key role in one of the often hidden forms of abuse reported by Amina — the prevalence of sexual assault by fathers-in-law and brothers-in-law.

Farah, 32, from Cambridgeshire, says she was sexually assaulted by her father-in-law when she was an 18-year-old newlywed.

She describes the abuse as starting subtly, with him “brushing against me or saying inappropriate things and passing them off as banter”. As Farah’s was an arranged marriage, she felt uncomfortable about raising concerns with her husband about his father’s behaviour. Her fears were realised when she was alone in the house with him and he grabbed her and forcibly kissed her. “He told me he didn’t see me as a daughter and that I aroused him. In our culture, your father-in-law is like your own father, so I felt sick.”

When Farah spoke to her family about it, “all hell broke loose”, she says: “My mother-in-law accused me of seducing her husband. The worst thing was my elder sister-in-law also called me a liar, even though I found out later he had done the same to her.”

Farah managed to get a divorce and has started a new life in another country. She believes that cultural pressure made it impossible for her to go to the authorities.

“Reporting it wasn’t even on my list. My priority was to escape and survive. If I had to drag it out in the courts, I’d never get away from them,” she says.

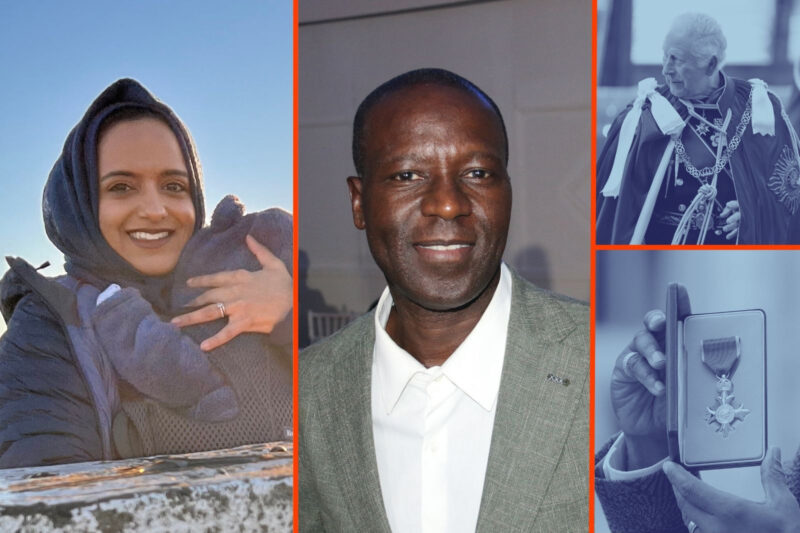

Nikki Hubbard MBE is a detective at the Metropolitan Police who spent 10 years as the national lead for honour-based violence and forced marriages. “In-law abuse cases are not uncommon, but it’s a taboo subject within the community, so these cases will not come to the police until they really escalate,” she says.

The biggest hurdle is encouraging people to report incidents to the police, she says. “If women do leave, they are ostracised from their families and communities. If they report it, they are seen as betraying their community.”

“It is too late for me, but I am trying to bring up my daughters to be strong enough not to go through what I did,” says Afsheen. “My mum always said, ‘Your real home is with your in-laws,’ but it’s not my home, it’s my coffin.”

Some names have been changed.

In the UK, call the national domestic abuse helpline on 0808 2000 247 or visit Women’s Aid. For the Amina helpline, call 0808 801 0301, and Savera UK on 0800 107 0726. Other international helplines can be found via www.befrienders.org.

Newsletter

Newsletter