‘I have never seen injuries in children like I saw in Gaza’: a surgeon shares her experience

Dr Mahim Qureshi, a surgeon from London, spent two weeks in Al-Aqsa hospital delivering vital aid to hundreds of patients

Dr Mahim Qureshi is a senior registrar in vascular surgery at a hospital in London. In April, she joined a team of international doctors who travelled to Gaza with members of the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP). Qureshi, who has been practising as a doctor for 17 years, was based in Al-Aqsa Hospital and delivered vital emergency medical aid to hundreds of injured Palestinians over the course of two weeks.

Since Israel’s assault on Gaza began in October 2023, more than 34,000 Palestinians have been killed and a further 70,000 have been injured according to figures from the Palestinian Ministry of Health. On 6 May, Israel issued evacuation orders for eastern Rafah, a city in the southern Gaza Strip where an estimated one million Palestinians are sheltering.

According to the IRC, there are currently no fully functioning hospitals in Gaza, and only 12 out of 36 offer limited treatments. Doctors and nurses also face limited supplies of fuel and essential medicines. The United Nations has said that analysis by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, an independent body that monitors food insecurity around the world, shows that 100% of Gaza’s population is at imminent risk of famine, which is further exacerbating medical needs.

Here, Qureshi speaks to Hyphen about her experience.

The interview has been edited for clarity.

Just days before we arrived in Gaza on 3 April, news broke that seven humanitarians working for the World Central Kitchen had died in Israeli airstrikes. Many of the parties in our convoy pulled out, but my team was resolute that we needed to go in.

I had longed to visit Palestine for many years. As we crossed the Rafah border from Egypt, we were greeted by Palestinian flags, and a large “I love Gaza” sign with a red heart. We felt welcomed by the city. Despite the tragic circumstances, in that moment I felt joy. I was finally here.

I had tried to prepare myself for what I might see in the hospital. I’d spoken with other professionals who had warned me about the overcrowding. When we arrived, there were around 3,000 people sheltering in Al-Aqsa. They came from all walks of life: engineers, doctors, labourers, farmers. There were so many people sheltering on the floor that you could hardly see the tiles. They greeted us with smiles, and children reached out with their hands.

My mornings would start with a walk around the ward to check on patients. I would then perform any operations that needed to be done alongside the hospital’s senior vascular surgeon, and then wait for new emergencies to arrive.

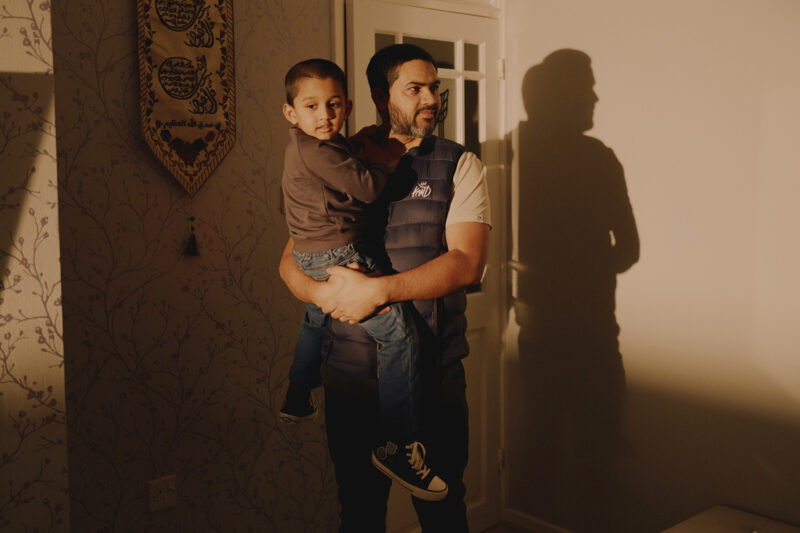

In all my years as a doctor, I have never seen injuries and illnesses in children like I saw in Gaza. An overwhelmingly disproportionate number of our patients were children. One morning I was asked to review a two-year-old girl who had been referred to vascular surgery because she had developed gangrene on some of her toes.

Looking at her blood results, we strongly suspected that she may have a childhood leukaemia. In the UK, the most common type of this cancer has a survival rate of more than 90%, but none of the investigations to confirm her diagnosis were available at Al-Aqsa. There was not one haematologist or paediatric oncologist. When we made inquiries outside of the hospital, it turned out that there was no one who could help this little girl. Her father was utterly distraught, and there was nothing I could do. I’ll never forget that.

The patients in Palestine are malnourished and hungry, and the sheer number of them meant that it was impossible to keep the hospital clean. On my floor in the hospital, there was one bathroom between hundreds of patients. Statistics suggest that in Gaza there is one toilet for every 200 people, and one shower for every 4,500 people.

Everything at Al-Aqsa was tightly rationed. There was limited access to water, which meant the sterilisation unit was not functioning as it should. Sterile surgical drapes were scarce and some single-use surgical instruments were used over and over again. Operating tables were lined with body bags that had already been used for previous patients and were simply being wiped down to use again. Dressings were also in short supply. The mattresses being used to transport people to and from theatre were filthy, most of them blood-soaked.

On top of this, many of our patients were undergoing amputations as a result of blast injuries, which frequently led to very contaminated wounds. In the UK I would expect a postoperative infection rate of 10% or less. In Gaza, it was 100%.

Aside from issues around hygiene, I was surprised by the lack of even basic equipment. There were few electric saws, which are necessary for major amputations. In terms of medical imaging, almost nothing other than X-ray was available. There was no CT scan for vascular investigations and no ultrasound. Angiograms — considered routine in the UK — weren’t possible in Gaza.

So much vascular surgery in the UK is minimally invasive, which leads to a quicker and easier recovery for a patient. But keyhole surgery is not an option in Gaza. My specialty requires me to operate on tiny blood vessels using appropriately sized instruments. These were not available in Gaza and this meant the type of operations we could perform were very limited, and we had to think carefully about what the likely outcome for a patient might be.

Now, as Israel begins its ground offensive in Rafah, my mind is cast back to my first day in Gaza where I saw so much destruction. I remember spending much of that drive in silence, and thinking to myself: “If there is an invasion, where will these people go? What will happen to them?”

News reports say Palestinians are being directed to a “humanitarian area” in Khan Younis and Al-Mawasi, but having driven through Khan Younis, I know that there are no roads or hospitals — it is uninhabitable.

From my experience, I know that much of the news from Gaza doesn’t provide the full picture. On 7 April, the BBC reported that ground troops near Al-Aqsa hospital were being called back by Israel. I was so happy, because we were used to the noise of bombs, firing, and the tanks. I went around telling everybody, but they smiled back at me like I was naive.

I soon realised why. In the days after the withdrawal of the ground troops, the aerial bombardment increased exponentially. The injuries that followed were even more horrific and indiscriminate. I didn’t see any news reports about that, so the gap between what is actually happening and what we know is extremely worrying.

Leaving Gaza was exceptionally painful. I felt I was turning my back and walking away from my own people at their greatest time of need. Deep bonds form quickly in such intense situations, and I hope to be able to return soon.

As told to Saman Javed.

Since October 2023, MAP has distributed more than £1.3m worth of medicines to hospitals in Gaza, and essential supplies, including hot meals, blankets and clothing totalling more than £1.9m, to displaced families. You can donate to MAP here.

Newsletter

Newsletter