‘Sending money to family abroad is an obligation, but sometimes it makes me angry’

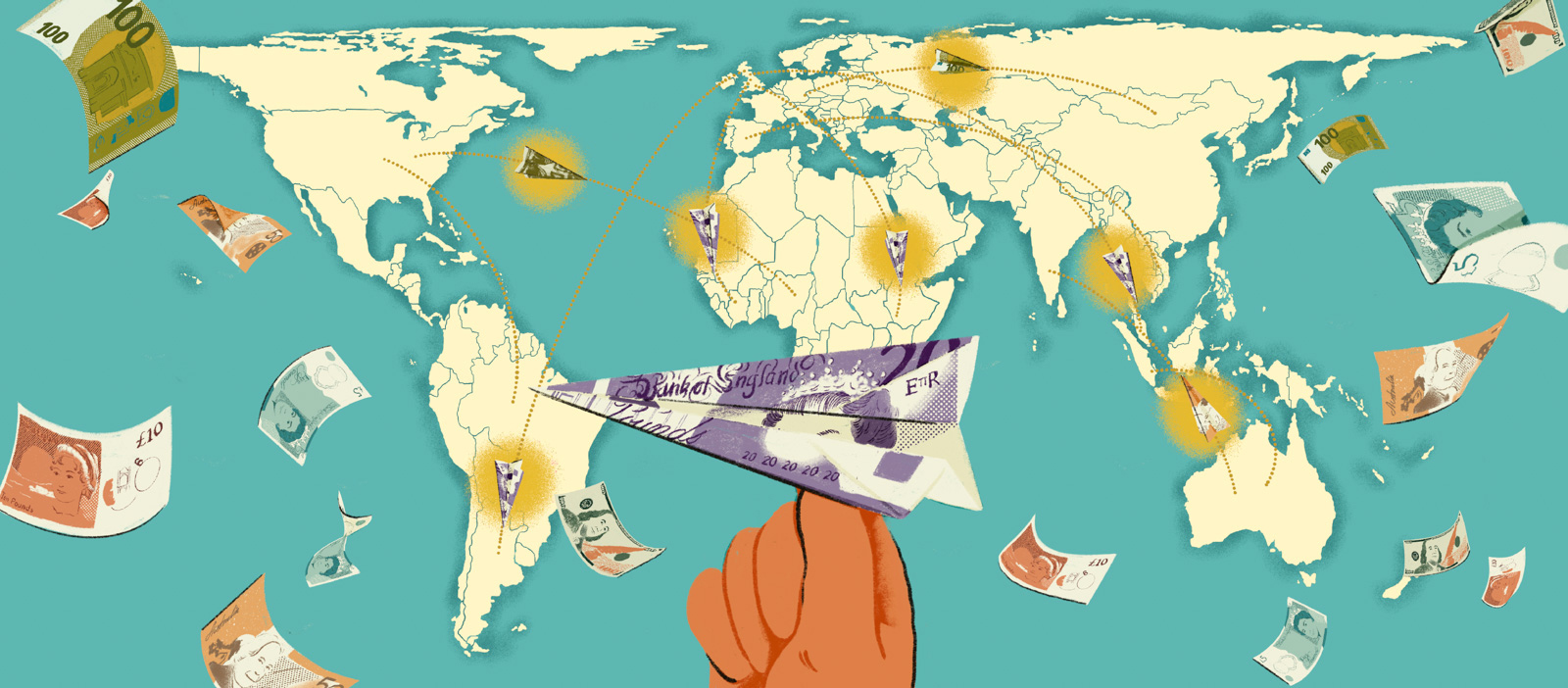

Around the world, a billion people pay or receive remittances. But now a younger generation is questioning the practice

Growing up, Yasin Bojang, 30, knew there would come a time when she would have to support her family. She just didn’t expect it to happen so soon. Her father, who she lived with in London, and her mother, who lived in the Gambia, separated when she was 21. When her father stopped providing for her two younger brothers, Bojang took on the financial responsibility.

Now, she sends about £250 every month to her mother and siblings, using the money transfer app Yayeh. Typically, the funds go towards school fees, groceries, phone credit and household expenses.

“Sending money to my family is very much an obligation. When my parents divorced, it became clear that either I help my family out, or they wouldn’t have enough to get by,” says Bojang. “The responsibility makes me angry at times. Given the choice, I wouldn’t take it on, but I’m grateful to Allah for putting me in the position to be able to support my mum.”

Bojang is among the one billion people globally who either send or receive remittance payments. The World Bank estimates people living in the UK send billions of pounds to loved ones abroad each year, with countries such as India, Pakistan and Nigeria among the top recipients.

While sending money to family members “back home” remains customary for older generations, the idea has lately sparked online debate among younger people. Some believe that they have an obligation to take on the same responsibilities as their parents and grandparents. Others consider it time for the custom to come to an end.

Some suggest that sending money to relatives is unsustainable, leading to family members becoming reliant on remittances. Others point to the financial hardships experienced by many in more affluent countries, resulting in people struggling to provide for themselves, their spouses and their children, but still having to make payments to family overseas, who believe that money is much easier to come by in countries such as the UK.

Despite those conflicting views, remittances are here to stay, according to Professor Kavita Datta, director of the Centre for the Study of Migration at Queen Mary, University of London. “Remittance is an age-old practice. Some individuals might stop, but new migrants will come along and replace those who have. As long as migration continues, so will remittances.”

For older generations, remittance payments have long been seen as a way to keep a place in the community one has left behind. This is especially important, as many people ultimately intend to go back to their countries of origin.

“Sending money is one way of maintaining that presence and keeping those relationships alive,” says Datta.

Many younger people, however, lack the same connections to the countries their parents came from. As a result, some consider that remittance payments monetise familial relationships.

“Several of my relationships have come to feel transactional over time,” says Bojang. “Some family members start expecting money because I live here in the UK. If I wasn’t helping them out, I don’t think we’d have a relationship. They want that support even though they don’t know my circumstances. It makes me not want to call some family members because I don’t know if that call will end with them asking for money.”

Research published by the international money transfer company Western Union in 2023 shows that migrants in the UK pay around 22% of their annual income in remittances. Two in five donors believe their family and friends would be forced into poverty without their help. Payments mostly go towards healthcare, food, accommodation and education costs.

According to the UN agency, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), more than 70 nations rely on remittances for at least 4% of their GDP. In the Gambia, where Bojang is from, such payments accounted for 28% of GDP in 2022. The growing global cost of living crisis has also made families increasingly reliant on relatives living overseas. But, feeling the pinch themselves, around 55% of migrants have reduced the amounts they send, according to Western Union.

At times, Bojang’s own financial commitments have left her unable to give as much to her mother and brothers as she has in the past. Although her mother understands that her daughter’s income can fluctuate, Bojang still feels a heavy responsibility towards her family.

“Being the eldest, there’s an invisible strike against us that we have to be prepared to support our family financially,” says Bojang. “I’m very conscious of how I spend my money in case of an emergency. I have to be ready to help whoever needs it.”

The increased financial obligations have affected Bojang’s relationship with her father. Now, they are barely on speaking terms. She has also had to draw boundaries between herself and some members of her extended family who she had previously helped.

Sending money overseas has also affected Abdullah Naseer’s relationships with family members. The 28-year-old chemical engineer from Stafford first began to send occasional payments to cousins in Nigeria during his first year of university.

‘With a couple of my cousins, I began to feel like they only spoke with me when they wanted money’

Now Naseer sends £50 every other month to domestic workers in his family home in Bauchi, Nigeria, and an additional amount to an aunt who is looking after his grandmother. Seeing the dedication of his family’s housekeepers when visiting, Naseer wanted to compensate them for their efforts.

Naseer has been living in Abu Dhabi for the past two years, and a tax-free income has allowed him to give more to his family than before.

“I’ve seen people in really desperate situations and sending them just £10 or £20 can alleviate that stress and pressure. That amount can go a long way,” he says. “Zakah is an important aspect of Islam, so by sending that money, you’re fulfilling part of your faith.”

Hassan Uthman, 30, also sees supporting his extended family in Nigeria as part of his religious duty. Around five times a year, the London-based hedge fund analyst sends between £50 to £250 to his mother, who distributes the money among family members.

“I’ve seen my parents do a lot more with less, so it wouldn’t sit right with me to not help my family,” he says. “When I’m in Nigeria, I’m able to see and feel people’s pain due to the cost of living. I’ve seen how crippling the country’s declining currency has been, so it makes me give more.”

For Uthman, watching his parents give back to their families was an inspiration. For others, however, it can be a source of acrimony.

“Across all generations, a sense of resentment can build up,” says Datta. “Some start to consider why should they have to forgo certain things, just so people back home, who they don’t even know, can continue to receive remittances.”

The feeling that older generations have been taken advantage of can make some younger people reluctant to make payments. For Uthman, though, the ability to have a positive influence on someone’s day-to-day life in Nigeria spurs him on.

“I think a lot of the conversations about this topic from our generation come from a trauma position, but people forget about the greater impact sending money back home can have,” he says.

As for Bojang, she believes that her generation has been able to set boundaries better than earlier generations and has the freedom to choose whether to support family, instead of it feeling like an automatic obligation.

“For our parents, back home is all they knew,” she says. “They always thought they would go back there, but we have so many more options. At the end of the day, people should do what’s right for their family context.”

Newsletter

Newsletter