‘I thought eating disorders only affected white women’

People from religious and cultural minorities face unique barriers on the road to recovery

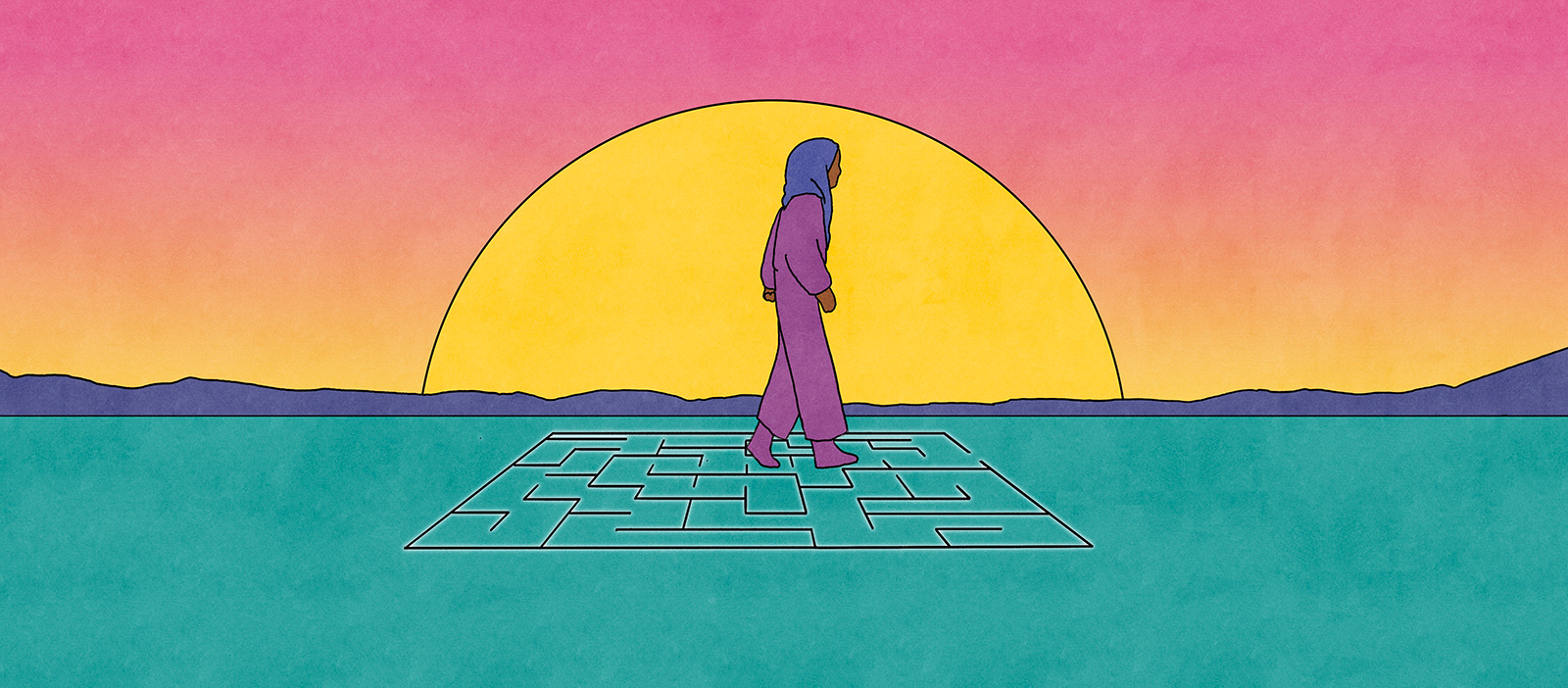

For much of her adolescence, Halimah struggled with an eating disorder. By the time the pandemic hit, her education was severely disrupted and she was dealing with anxiety and family-related issues. Restricting what she ate gave her a sense of control at a point when everything else seemed to be spiralling.

At first, she maintained a state of denial, refusing to acknowledge that she had a problem. Later, she put off seeking help, fearing that she would not be taken seriously by healthcare professionals. Eventually, though, she decided to talk to her GP.

“My mood hit a new low and my anxiety reached an ultimate high,” says Halimah, now 22. “My eating disorder was feeding off both, which was affecting my health, even if I didn’t want to admit it.”

After an assessment, she received a diagnosis of “other specified feeding or eating disorders” (OSFED) in June 2023. She is now undergoing cognitive behavioural therapy as part of her recovery process.

For Halimah, one of the biggest barriers to seeking help was that, as a visibly Muslim woman from a South Asian background, she felt she did not fit the stereotypical image of a person who could have an eating disorder. Growing up, she had never seen any media representation of women who looked like herself living with such conditions. As a result, she came to believe that they affected only white women and that her behaviour was normal.

“No one would ever look at me with a hijab and think, ‘She has an eating disorder’,” says Halimah. “I don’t look like that typical white girl. I wasn’t frail and I always wear baggy clothes for modesty, so you couldn’t see what was happening to my body.”

According to a 2019 YouGov survey commissioned by the UK eating disorder charity Beat, 39% of adults in the UK believe eating disorders are most common among white people. But, according to Beat, “clinical research has found that such conditions are just as common or even more common among Black, Asian and minority ethnic people”. The stigma often attached to eating disorders and mental illness in Muslim communities can make seeking help even more difficult.

According to Umairah Malik, a clinical advice coordinator at Beat, widespread misconceptions and lack of knowledge mean that eating disorders tend to go undiagnosed for longer in ethnic minority communities. “We have to ensure that the person with the eating disorder has the space to be able to talk about it without fear of judgement within their personal life and the health service too,” she says.

Those fears made family gatherings a dreaded affair for Halimah, leaving her feeling detached from loved ones and the wider Muslim community. “The adults around me didn’t know about eating disorders and it’s very much a cultural thing to comment about other people’s bodies,” she says. “I always felt like people were looking and judging.”

Another common worry among people from minority communities with eating disorders is that they might not receive culturally or religiously appropriate support.

“When some people go to therapy, they’re worried their specific challenges related to their community won’t be acknowledged,” she says. “At the same time, it might not be easy for them to talk about things within their family or community, particularly if there isn’t the language for it or if their experiences are not understood.”

For Amina, 24, receiving a diagnosis of anorexia took about four years, as her body mass index (BMI) was not low enough to be considered for a referral. Clinical research has shown that young people with eating disorders who are not “skinny, white, affluent girls” — also known as the SWAG stereotype — are less likely to receive a diagnosis or treatment.

“Eating disorders look different on all bodies,” says Amina. “The way my body loses weight and the way it looks isn’t necessarily the way people think anorexia looks.”

Amina’s mixed South Asian and Black heritage has played a large role in both her illness and her five-year journey of recovery.

“A lot of my eating disorder came from hating my body and culture,” she says. “When I began to get unwell, I thought the more I distanced myself from being Brown, Black and Muslim, the more people would like me, and that I would feel differently about my appearance. That was difficult to reconcile and I had to explore what beauty meant outside of the white gaze.”

So far, Amina has seen two therapists — one white and one of South Asian heritage — but felt that neither fully understood her faith or culture. She explains that, as a Muslim woman, others often automatically assume she is oppressed, which has discouraged her from discussing her identity in counselling. Now she has decided that if she returns to therapy she will seek out a Black practitioner.

“During my recovery, I’ve come to understand why my perception of beauty and body standards are warped sometimes,” she says. “This has helped me to unlearn and unpack my own internalised racism — specifically anti-Blackness — which sometimes feels too much to explain to someone who is not Black.”

Organisations such as Beat are keenly aware of the need for inclusive recovery treatments. Research conducted by the charity found that just 52% of people from minority ethnicities would feel confident seeking help for eating disorders from healthcare professionals, compared to 64% of white British people.

To help make culturally and religiously sensitive treatment more widely available, Beat runs workshops with healthcare professionals on diversity and how different identities can influence recovery. For instance, the dietary advice given to people with eating disorders rarely includes foods from non-white cultures.

“We have highlighted how some foods aren’t considered in meal plans offered by healthcare professionals,” says Malik. “If the food you’ve grown up eating is not there, it can make that recovery difficult and could even reinforce your eating disorder.”

Nadia Shabir has first-hand experience of that problem. In her mid-20s, she was admitted to an eating disorders unit where her usual meals were not available and there was no halal option. Shabir was determined to get out of the unit by any means necessary and focused on gaining the minimum weight required to leave, rather than building a better, lasting relationship with food.

“I was very resilient towards all the therapies,” says Shabir. “Even though I wasn’t used to some of the foods, I didn’t challenge the healthcare workers because they would have thought I was challenging the treatment.”

Eventually, Shabir, 40, found that a faith-based approach provided her best route to recovery. Prayer, meditation and reading about the healing properties of foods in the Qur’an have all helped to change her life. Since 2012, she has run a specialist website named Islam and Eating Disorders, which aims to increase awareness and remove stigma within the Muslim community.

“There was a time during my illness that I wouldn’t even leave my room,” Shabir says. “But for me, it was as simple as leaning into my faith more. I now no longer have anxiety or depression, and I don’t focus on my body image. When I was looking for help online, there was nothing there. Now I’m able to help people worldwide.”

Some names have been changed.

● Beat has helplines for England (0808-801-0677), Scotland (0808 801 04320), Wales (0808 801 04330) and Northern Ireland (0808 801 04340). NHS Choices provides information and advice on overcoming eating disorders for sufferers, family and friends in the UK. Islam and Eating Disorders provides a list of charities, support groups and helplines.

Newsletter

Newsletter