Hassan Nazer Q&A: ‘My films are a voice for my country’

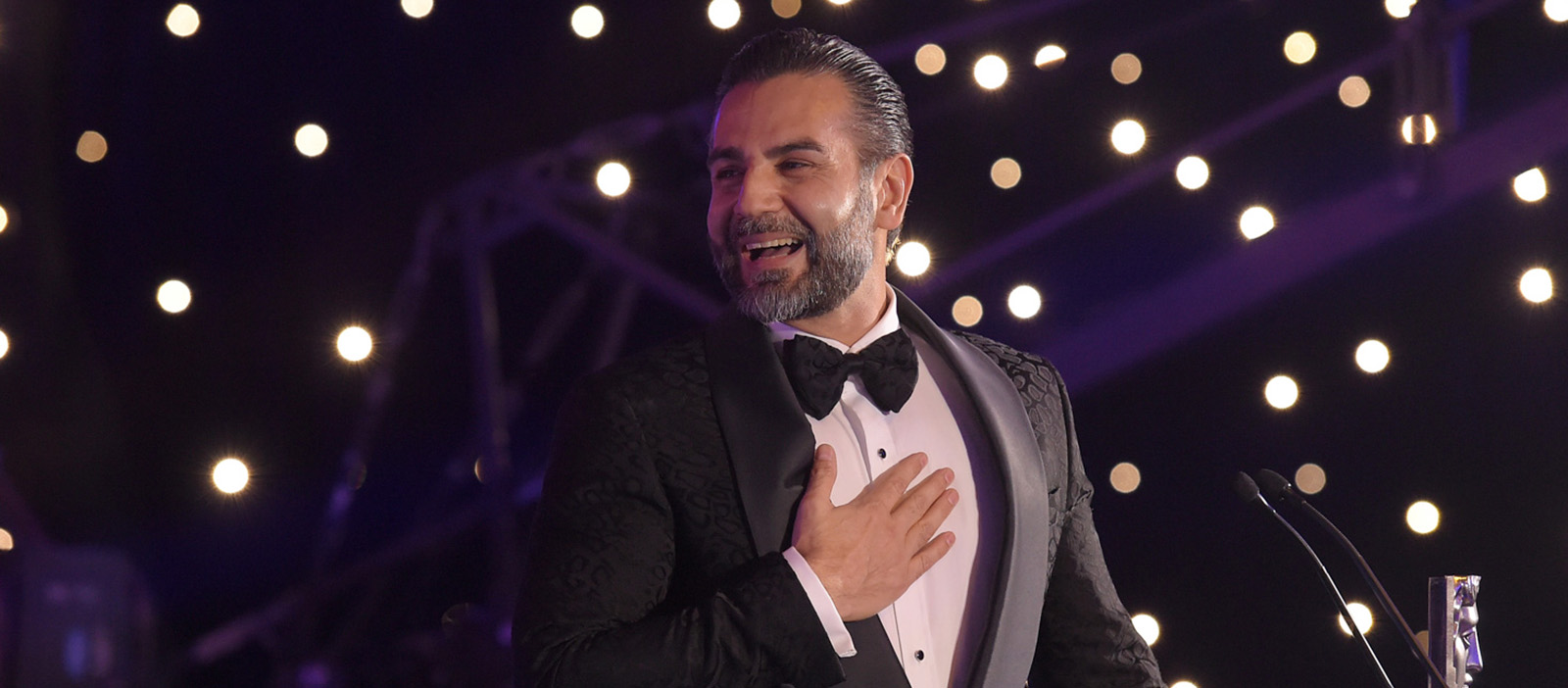

Hassan Nazer arrived in Scotland as a refugee from Iran in 2000 but has returned since to make his films. Photo by Antony Jones/Bafta/Getty Images for Bafta

The award-winning director on censorship and his enduring love for the greats of Iranian cinema

When Hassan Nazer first arrived in Scotland as a refugee from Iran in 2000, he was determined to carve out a career as a filmmaker and to share his love for Iranian cinema. Fast-forward to 2023 and Nazer’s fourth full-length movie, Winners, has picked up the title of best feature film at the Bafta Scotland Awards and was chosen as the UK entry for best international feature at the 2023 Academy Awards.

After years of self-financing his work, Winners is Nazer’s first film to be fully funded by outside backers. The plot is based on the Iranian director Asghar Farhadi’s refusal to attend the 2017 Academy Awards, in response to then-US president Donald Trump’s Muslim travel ban. Unable to pick up his Oscar, Farhadi’s statue is sent to him in Iran, but gets lost in transit.

Set in a small Iranian town, the action centres on nine-year-old Yahya (Parsa Maghami), and his friend Leyla (Helia Mohammadkhani), who find the statue while scavenging the local rubbish tip for recyclable plastic to sell. With the help of their boss, Naser Khan (Reza Naji), they attempt to return it to Farhadi.

Here, the Aberdeen-based director talks about film censorship in Iran and the responsibility he feels to tell stories from the country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get into filmmaking?

I was involved with theatre throughout my education. When I moved from my hometown of Garmsar to Tehran, I took theatre courses under the legendary Iranian director Hamid Samandarian. I wanted to make theatre bigger in Iran and to get more women involved, particularly in my hometown, but the community wasn’t ready to have women on the stage. I was red-flagged by officials and my uncle advised me to leave the country if I wanted to further my career.

I studied film and visual culture at the University of Aberdeen. Then, about 12 years ago, I decided to make my first feature film, Black Day. In 2011 the government in Iran was giving people who had left the country as refugees the opportunity to go back without any issues. I took the chance and returned to make my very first feature.

Iranian films and filmmakers are often subject to censorship. How do you balance those cultural limitations with telling your stories authentically?

Censorship is one of the biggest barriers to filmmakers in Iran. With recent incidents in terms of women’s rights and the different movements happening in the country, people are very worried that cinema will change direction, but I’m not worried about it because Iranian filmmakers will always find a way. The director Jafar Panahi faced a travel ban for 14 years, but during that period, he still made several successful films such as Taxi Tehran (2015) and No Bears (2022). We know we could face censorship, but with creativity, we will resolve that.

What inspired the story of Winners?

I always wanted to make a film about my love of cinema. It wasn’t until 2016 that I started developing the idea. Then, I was watching the Oscars in 2017, when Asghar Farhadi won the Academy Award for best foreign language film. He boycotted the ceremony because of Donald Trump’s Muslim travel ban. The idea of what would have happened to his award sparked the plot of the film. I wanted to showcase the influence of iconic Iranian directors — for example, Abbas Kiarostam and Majid Majidi — as well as Iranian actors, such as Reza Naji who stars in the film. It was important for me to celebrate their lives and work.

What do you want your viewers to learn about Iran from your work?

It’s very important to me to introduce my home country to the rest of the world, in particular its literature and history. The location I selected to feature in Winners wasn’t the most beautiful place in the world — it was my hometown. But it was still important to share on screen, alongside beautiful places in Tehran. Even though it isn’t the most aesthetic place, it came across as a loving environment. I think people will be able to replace the characters with themselves. It doesn’t matter that the story is set in Iran. It could have happened in France, north America, or South Korea. Cinema is a universal language.

Do you feel a special responsibility to tell Iranian stories?

I always felt a need to do something for Iran. When I received the Bafta award, the first thing that came to my mind on stage was that I had to thank Scotland and Iran. I thanked Scotland for supporting me and allowing me to bring my culture and share it with an audience. I also thanked Iran and my Iranian team for helping me make the film. My aim with filmmaking has always been to be a voice for my country. I describe myself as Iranian-British, but I have more of a duty to introduce Iranian culture and to show the good side of Iran. Cinema is a weapon for us.

Newsletter

Newsletter