Protect yourself from evil — for as little as £3.50

Celebrities and wellness brands are embracing the distinctive blue and black nazar jewellery, believed by some to ward off envy and negativity

–

Ceyda, a British Muslim of Turkish origin, grew up heeding her parents’ warnings about the dangers posed by those who might envy her. To protect themselves, her mother and father kept blue and black amulets around the house to ward off evil. “My parents always told us they were to keep jealous eyes away,” said Ceyda, a TV producer who lives with her husband and two children in the north east London suburb of Walthamstow.

Ceyda, who did not want to reveal her full name, added: “If I have something nice and someone looks at it with envy, they believe that the nice thing will get ruined somehow. The amulets protect us from evil eyes and evil spirits.”

The eye-shaped amulets, also known as nazar, are a traditional gift given to both children and adults to mark milestones such as birth and marriage. For Ceyda, they are an intrinsic part of her Turkish heritage. “I wear one everyday — one on a necklace and often one pinned to my bra. I think of it as quite a personal thing. I like knowing it’s there but not on show.”

Anyone who has travelled to Turkey, Greece or even Mexico has likely stopped to look at market stalls and shops selling the blue, white, and black glass circles which claim to offer the buyer protection from malice and negative energies. In the UK, they are often found in both wellness shops and Turkish supermarkets.

Once the preserve of superstitious grandmothers, in the past few years nazar jewellery has gained broader popularity — the online store Etsy currently yields over 210,000 search results for the term. Often sold as necklaces, anklets or bracelets, they retail from as little as £3.50, rising to pieces costing £2,690 worn by Meghan Markle. Even the Unicode consortium, the organisation that maintains the standards for digital scripts, including emojis, has got in on the act, offering two “evil eye” emoji options, launching a nazar amulet emoji in 2018 and a hand emoji in 2021.

The popularity of nazar jewellery also mirrors the explosion in interest in wellness over the last decade and the success of brands like Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop and Kourtney Kardashian’s Poosh. According to a 2023 study carried out by The Global Wellness Institute, the wellness industry is now worth $5.6tn worldwide. The nazar emblem, with its distinctive design and vibrant colours, slots in easily alongside already ubiquitous mood-lifting candles, health gummies, and so-called energy crystals.

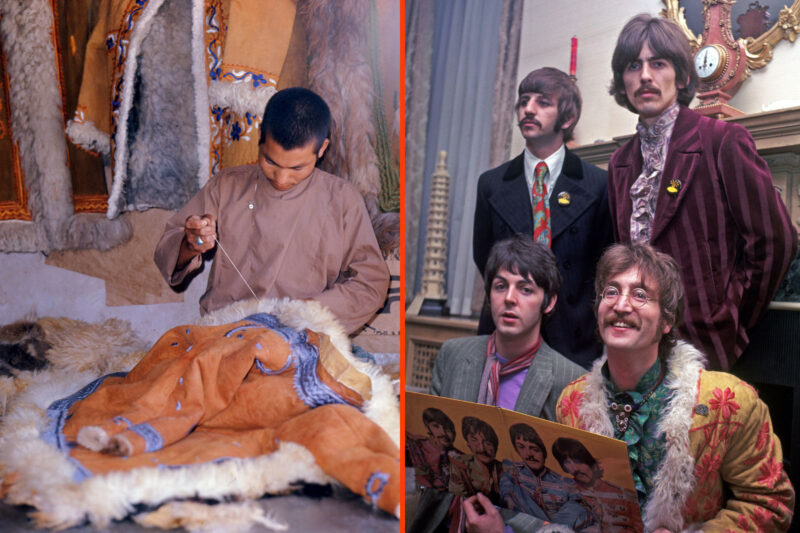

Belief in the notion of the evil eye and amulets that dispel the curse go back thousands of years and span a number of cultures throughout the world, with the earliest version dating all the way back to 3500BC Mesopotamia. The symbol has also become associated with protection in Islam, based on the belief that the evil eye is most commonly given in the guise of a compliment filled with hidden envy or jealousy rather than with openly hostile intent.

The concept of the evil eye is also mentioned in the Qur’an, “And from the evil of the envier when he envies.” [Al-Falaq 113:5].

A number of people interviewed for this article declined to divulge their full names. “I’ve always grown up with the superstition that they ward off nazar, and that whether it’s intentional or not we all give evil eye and are all victims to it,” said Hala, a British Muslim of Iraqi heritage, who did not want to reveal her full name. Hala owns several amulets, including a keyring and a rearview mirror charm for her car.

‘They were all gifts from family, but I’d purchase them myself if it wasn’t something I’d received. The eye helps to protect you from the impact of the curse or sin of jealousy.’

The significance of the symbol amongst Muslims arises from cultural practices that have developed over time. “When the Turkic people converted to Islam, they had two other strong influences into their daily culture: the Christian culture they came across while they were migrating, and their pagan nomadic Central Asian roots, in which the belief in charms and talismans is very powerful,” explained Neşe Yildiran, professor of art history at Istanbul’s Bahçeşehir University.

“Nazar belief can be found in Iran, or in Iraq which had been dominated by the Ottomans for a long time,” she added. “This is not the same situation for other Islamic communities: the socio-cultural tendencies are going to be different for each country.”

Aside from its popularity within wellness circles, the beliefs ascribed to warding off malice have also taken root in cultures far from the Middle East and central Asia. “I’ve always had the amulet in my home, a cherished part of my upbringing to safeguard us from the evil eye or el mal de ojo” said Kaylani Sanchez, a New Yorker of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent.

“Over the years, I’ve come to value its presence, with one adorning my home, another gracing my office, and a third watching over me in my car. Recently, I decided to continue the tradition by gifting one to a close friend who had just purchased a new apartment, sharing the protective symbol with new homeowners as a meaningful gesture.”

Ceyda from Walthamstow plans to pass on the tradition to both her children, who are half-English. “I’ve got lots of nazar bonçuks [beads] on gold for the kids that were gifts from my Turkish family,” she said. “I will definitely explain it to them when they’re older, and want them to have them in their homes.”

Newsletter

Newsletter