What a difference a spray makes

From halal portable bidets to non-Muslims installing shatafas, personal hygiene is undergoing a fresh, new makeover in the UK

–

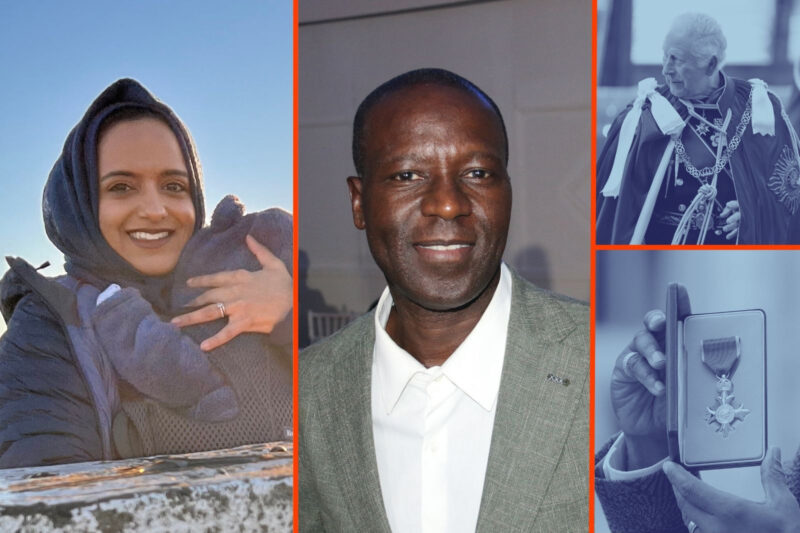

Back in March 2023, Kumail Medavi was taking a train from Croydon, where he lives, into central London, hoping to secure a life-changing business deal. For years, he had been spending the time between his day job and family responsibilities working on a tech start-up — an app that would utilise blockchain technology to revolutionise money transfers. Medavi, 34, sent hundreds of emails and LinkedIn messages to potential funders and companies he wanted to try out the technology, but all to no avail. Finally, one firm, based in the financial district of Canary Wharf, was willing to hear his idea.

As you might expect before such a high-stakes meeting, Medavi needed to visit the bathroom as soon as he arrived at London Bridge station. There, he found that, of the two stalls that worked, neither had any toilet paper. He began a frantic search for nearby bathrooms but had no luck. Almost all were out of order or had no paper. Meanwhile, the handful of restaurants clustered around the station required people to order a meal before being allowed to use their lavatories. Medavi didn’t think it would look professional to show up at his meeting carrying a takeaway box of pasta.

While he generally tends to avoid using public toilets, Medavi couldn’t muster the strength to hold it in. Desperate, he resorted to going into a local pub — something he’d have rather not have done, given his religious beliefs — only to find it offered just a few sheets of kitchen roll, thicker than toilet paper and designed to clean surfaces rather than skin. He arrived at the meeting late and feeling uncomfortable. “While I was giving the presentation, all I could think about was wanting a shower,” he remembers.

Like most Muslims, Medavi routinely washes with water after using the toilet in a ritual known as istinja, which is considered obligatory in Islam. While it is well known that believers must perform ablutions, or wudu, before prayers, many consider it essential to be clean at all times. To have not washed after using the bathroom is considered to be in a state of najis — uncleanliness — which prohibits a person from praying or handling religious items, such as the Qur’an.

To wash in accordance with Islamic rules requires the use of fresh water, which has for centuries been contained in a vessel known as a lota. More modern systems include the shatafa, a spray hose connected to the toilet. While both can be easily found in Muslim countries, they are far less common in the west, particularly in the UK, where even European-style bidets have long been considered foreign and unnecessary. Accordingly, European Muslims are usually advised to avoid public toilets wherever possible or to carry a water bottle with them for cleaning.

More recently, others — myself included — have been extolling the virtues of the new generation of portable bidets. Lightweight and compact, such devices are particularly useful for office workers and commuters. I began using mine a few months ago, after years of bad experiences with toilet stalls across the country.

The challenge of finding a functioning and fully stocked toilet is not limited to Muslims. A recent investigation by the Liberal Democrat party found that, owing to local council budget cuts, there has been a 19% decrease in publicly accessible bathrooms in England since 2017. The Royal Society for Public Health has also warned that the lack of available facilities discourages people — particularly those with disabilities — from leaving their homes and heightens public health risks, from urinary infections to the spread of e.coli and noroviruses.

For Muslims, though, the lack of facilities in offices, restaurants and in public buildings where it is possible to wash with water present particular challenges. Some of the individuals interviewed for this article said they often refused invitations to socialise to avoid having to use shared bathrooms.

Travel bidets are now widely available from online retailers and many have been promoted on TikTok by Muslim influencers

Samira, 25, says she carries extra bottles of water and a small lota to work, but still tries to avoid using the toilet when there.

“One time a colleague saw me walking out of the bathroom with a two-litre Evian bottle,” she recalls. “I had to make an excuse and say someone left it in there and I was about to throw it out. I was worried that if I tried to explain it, it would end up being the subject of weird office gossip.”

Other Muslims who use the water bottle method note its deficiencies. “I have health issues that mean I need to use the toilet several times a day,” says 38-year-old handyman Hasan. “There have been times when I’ve been between jobs and realised that I’ve left my bottle at another site, so I end up having to buy another one, or using the one I’ve been drinking from.”

Travel bidets are now widely available from online retailers, including Amazon and AliExpress, and many have been promoted on TikTok by Muslim influencers. Most of the products on the market, produced by companies with names such as HappyPo and Tonelife, are not made with Muslims in mind, though. Instead, they are primarily used in maternity care.

In recent years, however, a number of portable bidets have been created specifically for Muslim users. Manufacturers include the UK-based Wudumate. The company’s “personal kit” comprises a foldable plastic bag modelled on the traditional lota, which holds up to a litre of water and comes with a 45-degree nozzle.

The product, launched by Slough-based designer Moazzam Ali in 2008, has been bought by thousands of customers across Europe. According to WuduMate’s managing director Nigel Bromilow, the company’s other products, which range from home toilets with integrated washing capabilities to separate bidets and shatafas, have undergone a surge in popularity since the Qatar World Cup — most likely the first time many non-Muslim football fans had encountered such devices.

While It’s unclear how big the UK bidet market is, companies such as Victorian Plumbing, Boss Bidet and Tushy UK all cite a significant increase in the number installed since 2020, when Covid-19 lockdown-induced panic buying led to chronic shortages of toilet paper across the country. While WuduMate’s post-World Cup spike in sales may have died down, Bromilow says there is still interest in bidets among British consumers, which can be partly attributed to concerns over the environmental impact of toilet paper.

Whether the increasing popularity of bidets signals a broader change in British hygiene habits is yet to be seen. Rose George, a journalist and author of The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters, suggests that the country has a long way to go before bidets become commonplace. One of the challenges, she believes, is convincing the wider British public to shift away from the tissue paper they grew up using.

“Habit is a powerful thing and if people who used toilet paper are told there is nothing wrong with it — which is a mistake — why would they change?” she says. “Even the toilet is known as a distress purchase: we upgrade or replace it only when it’s broken.”

George, who has a Japanese toilet installed in her home and uses portable bidets while travelling, adds that such a cultural shift would require greater openness when talking about matters of public hygiene. That change in conversation could, however, make many Muslims feel much more comfortable using public bathrooms.

“Carrying a soft drink bottle or hiding watering cans in bathrooms… it’s daft,” she says. “There’s nothing shameful about wanting to have a clean anus.”

As Medavi expected, his pitch was rejected — a blessing, he believes, as he has since begun to work on new projects, including an AI system that he hopes will help new Muslims learn how to read the Qur’an. Looking back, he sees his experience as one containing valuable life lessons beyond just showing up at meetings earlier than he used to. Now he carries a bottle of water whenever he goes out. “It’s nice to know I won’t have to run around London searching for toilet paper,” he says.

Newsletter

Newsletter