The fight-back against anti-mosque campaigners

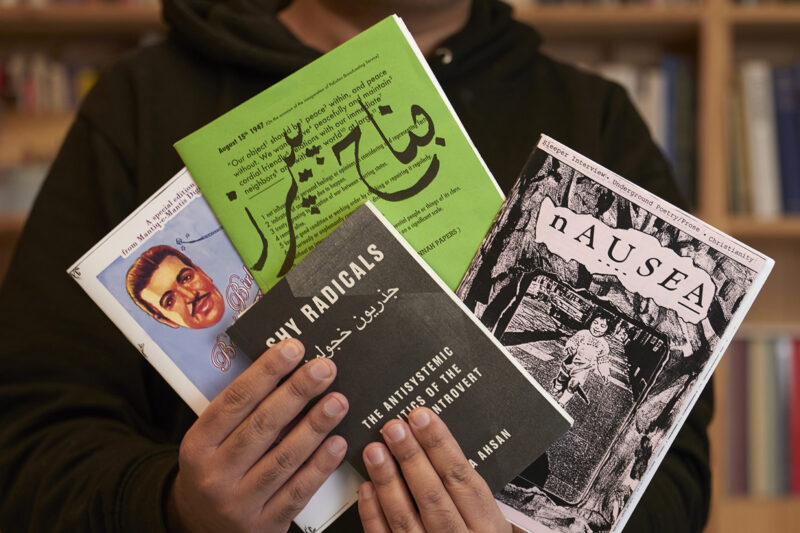

How one anti-extremist researcher developed a counter-misinformation strategy to oppose campaigns against new Muslim places of worship

It was early January 2022 when Zahed Amanullah received a call from a friend. “There’s a video you should take a look at,” they told him. Amanullah opened the YouTube link, sent via WhatsApp. A middle-aged man wearing a shirt and tie was speaking to a camera, explaining that he had been asked to “help resist” a planning application for a mosque in Harrogate.

“If you help save one place this year, then help save this one,” he said, asking viewers not to let the historic building — a former social club for second world war veterans — “fall to the enemy”.

Amanullah recalled breathing in sharply. The man in the video, a Bristol-based planning lawyer named Gavin Boby, was talking about the same building that Amanullah and members of Harrogate’s Muslim community had recently asked to be converted into a mosque via the local council’s planning department.

A quick Google search revealed that Boby, who has just under 4,000 followers on YouTube, advises ordinary people how to exploit planning laws to stop Muslims upgrading or obtaining planning permission for new mosques. Over the past decade, Boby, a self-styled “mosque buster”, claims on his website to have “won” 58 of 95 planning refusals around the UK.

“I felt scared,” Amanullah said. “It made me realise we were unprepared. We needed to act fast.”

Opposition to the building or expansion of mosques is nothing new. Organised campaigns have sprung up all over Europe and North America over the past two decades, perhaps the most famous being the demonstrations against the so-called “ground zero mosque” in Manhattan in 2010. A group named “Stop the Islamicization of America” organised a series of protests of several hundred people against plans to build a mosque near where the Twin Towers were destroyed.

Amanullah could see that Harrogate’s small Muslim community wasn’t about to face crowds of people waving placards, but something more sophisticated: a campaign of formal complaints lodged against the new mosque through official channels. Amanullah, an anti-extremism researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue thinktank, knew that Boby’s video didn’t break any social media platform guidelines as he doesn’t use language that could be construed as hate speech, so the community would need to find new ways to defend itself from his campaign.

Amanullah decided on the best way to fight back. He put together a “pre-bunking” campaign — a strategy designed to fight disinformation before it has had a chance to take root.

Amanullah, who is originally from San Francisco, his wife and two children first moved to Harrogate, a picturesque North Yorkshire spa town with a population of 165,000, from London in 2013. Back then, the Muslim community was still very small. Local Muslims were using a private apartment as a makeshift mosque, with around 10 people squeezing into a spare bedroom for evening prayers during Ramadan.

Over the years, the community grew to around 150 people, with some families moving from nearby cities such as Leeds in search of more greenery and better housing and schools. They were joined by refugees from war-torn countries such as Syria, and others from as far afield as Tunisia, Nigeria and the US. The Muslims soon outgrew the makeshift mosque in the spare bedroom and moved into a local church hall.

In 2020, they decided it was time to start fundraising for £500,000 to buy a permanent space. “We were never going to grow as a community without it,” said Amanullah. “We couldn’t figure out what kind of practice, activities and identity we would have unless we had a place we could call our own.”

After viewing a few buildings, the future mosque’s organising committee came across an old veterans’ space, the Home Guards Club. A Grade II-listed gothic-style building in a prime city centre location, it had been empty since 2015 and was in serious need of repair, with holes in the roof and dry rot. But its central location was perfect, and the building could accommodate up to 200 people for Friday prayers. Committee members bought the building in January 2022 and put in a planning application to Harrogate Borough Council.

Amanullah received the YouTube link from his friend only two weeks after putting in the application. He had suspected the building’s history as a social club for second world war Home Guard members would spark some well-meaning but misplaced concern about “British values”. “Harrogate really represents Englishness in a way that just a handful of cities up and down the country do,” said Amanullah — but this was something altogether unexpected.

Just a few days after the video, Amanullah’s phone pinged with a text from a different friend. “I got this through my door,” the message said. The message came attached with a picture of a flyer headlined “Should the council permit a new mosque at this location?” Whoever had printed and distributed it had left no name or contact details, but had listed the concerns Boby often encourages his followers to use when objecting to the building or expansion of mosques: issues pertaining to traffic, parking, and the preservation of local heritage.

The UK’s Muslim community, like other minority religious groups, has long been the focus of disruptive campaigns by far-right activists. Throughout the 2010s, groups such as Britain First and the English Defence League regularly targeted proposed mosques around the UK with overtly racist campaigns. One of the most high-profile saw Britain First target Maidstone mosque, which had received permission to expand and upgrade its premises to a three-storey building in 2016. Between 2017 and 2019, up to 25 campaigners with placards regularly demonstrated outside the local community’s then-tiny building, attracting national media attention.

Dr Muhammed Shabbir Usmani, Maidstone’s imam, told me that even though the protests were small and legal, they made members of the local Muslim community feel “very vulnerable and targeted”. Usmani and his colleagues instead found playful ways to try to placate them — for example, on one rainy afternoon, they invited demonstrators inside for coffee, tea and biscuits. “They were much quieter after that,” he said.

These aggressive protests have largely fizzled out, perhaps because they were ineffective, and possibly because they backfired. “They actually drove a lot of sympathy for Muslims,” said Amanullah. In Maidstone, local people started staging counter-protests that soon dwarfed those of Britain First. Anti-racist activists also donated money to the mosque’s fundraising campaign.

Gavin Boby’s legal activism began in 2013. He claims to have played a part in targeting sites in Ealing, York, Blackpool, Bolton and elsewhere. Although he uses his YouTube videos to tell followers not to engage in racist behaviour, Muslim communities have complained of racist objections by locals in cases he has previously been involved with, such as a 2017 campaign against plans for a mosque in Golders Green, north London. It is also impossible to confirm whether every “win” he lists on his website is down to his tactics alone, or whether some were refused planning permission for other reasons.

Boby, who crowdfunds his campaigns through his website, did not respond to several emailed requests for comment for this article.

In Harrogate, news that flyers objecting to the new mosque were being distributed sent ripples of fear through the Muslim community. “Some people thought it would be better to stay quiet,” said Amanullah. “They didn’t want to become a public face.”

Amanullah was convinced that Harrogate’s Muslims needed to act before the flyers spread further. He started putting together a campaign that would anticipate the various arguments from those objecting to the new mosque, and put answers in the public domain before those talking points took hold.

He combed through Boby’s online resources and made detailed social media threads addressing all potential concerns. For example, to counter worries about parking, he explained that attendees would use a nearby, empty multi-storey parking block. He also wrote detailed posts on Harrogate Islamic Association’s website, Facebook and Twitter accounts about the building’s heritage and how it would be preserved.

“The building is next to a school, and we assumed they’d say things about grooming,” he said. “It’s difficult and awkward to even respond to that, you know. But we said no activities would be happening during school hours. And we pointed out that some of our kids go to this school as well.”

Amanullah also recruited younger members of the Muslim community who were adept at using social media. They posted Amanullah’s talking points on Harrogate Islamic Association accounts so that no one would be singled out individually.

The digital engagement seemed to have a positive effect. Every time local media published stories about the new mosque, members of the community used it as an opportunity to repeat Amanullah’s pre-bunking points. Gradually, more and more people began posting messages of support, and defending the community. Yet, as the anti-mosque campaign spread on social media, several anonymous Twitter accounts popped up, parroting anti-mosque arguments. Few of them were based in Harrogate, according to Amanullah, who said that they appeared to be run by a small but highly organised group of people from all around the UK.

In March 2022, the public consultation on the planning application closed. The community’s work paid off: 60% of all public responses were in favour, and planning permission was granted. Harrogate resident David Hodgson was one of the people who submitted positive responses after findinding out about the campaign from local media.

“I took a look at the planning responses and I could see something darker was going on,” he said. “People were trying to make sensible-sounding arguments, but they couldn’t resist adding something anti-Muslim at the end.”

Boby posted a video lamenting the decision, promising to “keep fighting”. As news spread, the anonymous social media accounts, which had been sticking to more acceptable talking points, began posting outright Islamophobia.

A new Twitter account named “anglicus front” suddenly appeared, describing itself as a “protest group” against the “growing” Harrogate Muslim community and calling for demonstrations. Hodgson, Amanullah and others quickly reported the accounts to Twitter and got them taken down. The community nervously waited for the day of the protest, but it came and went without incident.

Amanullah has since been working on a toolkit that other communities around the UK and elsewhere can use to protect themselves. “It’s not difficult. Anyone can do it,” he said, pointing to existing and free online pre-bunking guides, including one by Google.

Boby is still posting videos on his YouTube channel almost every week, with a recent one calling for “mass repatriations” of immigrants from the UK. The old Home Guards Club is being stripped out and renovated, and Harrogate’s Muslim community is wary that anti-mosque or racist campaigns might flare up again once the religious building nears its scheduled opening at the end of the year.

This time, however, they will be prepared. “I think we caught them off-guard,” said Amanullah of the anti-mosque organisers. “I don’t think they knew that a Muslim community would understand social media and that we would push back.”

Newsletter

Newsletter