Malcolm X’s visit to the Midlands still holds lessons for today

In 1965, the late civil rights campaigner witnessed the discrimination faced by Black and South Asian workers in the town of Smethwick

–

In late October 2022, Avtar Singh Jouhl, the national president of the Indian Workers’ Association and a pivotal figure in the UK anti-racist movement, was laid to rest at Sandwell crematorium. Born in the Punjab region of India in 1938, Jouhl arrived in Britain and had settled in neighbouring Smethwick in early 1958.

For more than 28 years, he worked at a local foundry. A committed trade unionist, he understood the importance of workers’ solidarity, sending coaches of IWA members to support the miners’ strike in 1984. He was also instrumental in coordinating a lesser-known event: Malcolm X’s visit to the West Midlands in the mid-1960s.

“I was in Birmingham, Alabama, the other day. This will give me a chance to see if Birmingham, England, is any different,” said Malcolm X to the press on 12 February 1965.

The US city he referenced had established itself as a pivotal site of the civil rights movement. Once described by Martin Luther King as “probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States”, it took centre stage during a hard-won campaign of non-violent direct action to change that reality.

The UK’s Birmingham was different from its American namesake in many ways, but shockingly similar in others. Pubs and clubs maintained colour bars; toilets at foundries and factories were often segregated. For Black and Asian communities, even a haircut at a local barber’s was often out of bounds.

A towering figure in the civil rights movement and a leading member of the Black nationalist Nation of Islam, Malcolm had once preached racial separatism as the only viable solution to such problems. But his visit to Britain came at a pivotal moment in his life. He had broken away from the Black nationalist Nation of Islam, become a mainstream Sunni Muslim, performed hajj and travelled extensively across the Middle East, Africa and Europe. A skilled orator, he captivated audiences from Boston to Beirut with his powerful and unapologetic advocacy for racial justice.

Malcolm X believed that just as racism, colonialism and imperialism are global phenomena, so too must be the resistance to them. That internationalist mentality explains why he decided that visiting a working-class community in the Black Country formed part of his mission.

In the 1960s, Smethwick offered a perfect illustration of the hostility faced by people of colour across the UK. Immigrants from Britain’s former colonies in the Caribbean, Africa and the Indian subcontinent had come to Britain to fill postwar labour shortages in the UK, many of them taking up jobs in Britain’s factories, mills and public services. Many landlords refused to rent properties to them, forcing thousands to live in overcrowded, slum-like conditions. Meanwhile, calls for immigration control were loudly persistent and racist violence frequent.

“This is worse than America. This is worse than Harlem,” said Malcolm X as he walked down Marshall Street, a road lined with rundown housing in the west of Smethwick. Just a few months earlier, a campaign had called on the local council to buy up empty houses and make them available exclusively to white families. As he passed the red brick terraces, he was heckled.

“We don’t want any more Black people here. What’s your business here?” asked one white resident.

Animosity towards Black and Asian people was also embedded in law. The passing of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act had ushered in racialised policy that restricted immigration from the Caribbean and South Asia. Under the Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan, the state played an active role in stigmatising minority communities. The “colour problem” became part of the public lexicon, particularly after the Nottingham and Notting Hill riots of 1958, sparked by a string of racist attacks on Black residents.

While in Smethwick, Malcolm X visited a local school and walked through the town. While doing so, he witnessed first-hand the colour bars enforced by many businesses. Among the most stark examples were the signs hanging outside numerous drinking establishments, stipulating that “No Blacks” were allowed in.

“You know we don’t serve Blacks,” said a barmaid at the Blue Gates pub on Smethwick High Street, refusing his entourage entry. Even Smethwick Labour Club operated a colour bar. In contrast, members of the local South Asian and Black communities greeted him with enthusiasm, viewing him as a man who not only understood their situation but articulated their desire for a better and more equitable life with passion and clarity.

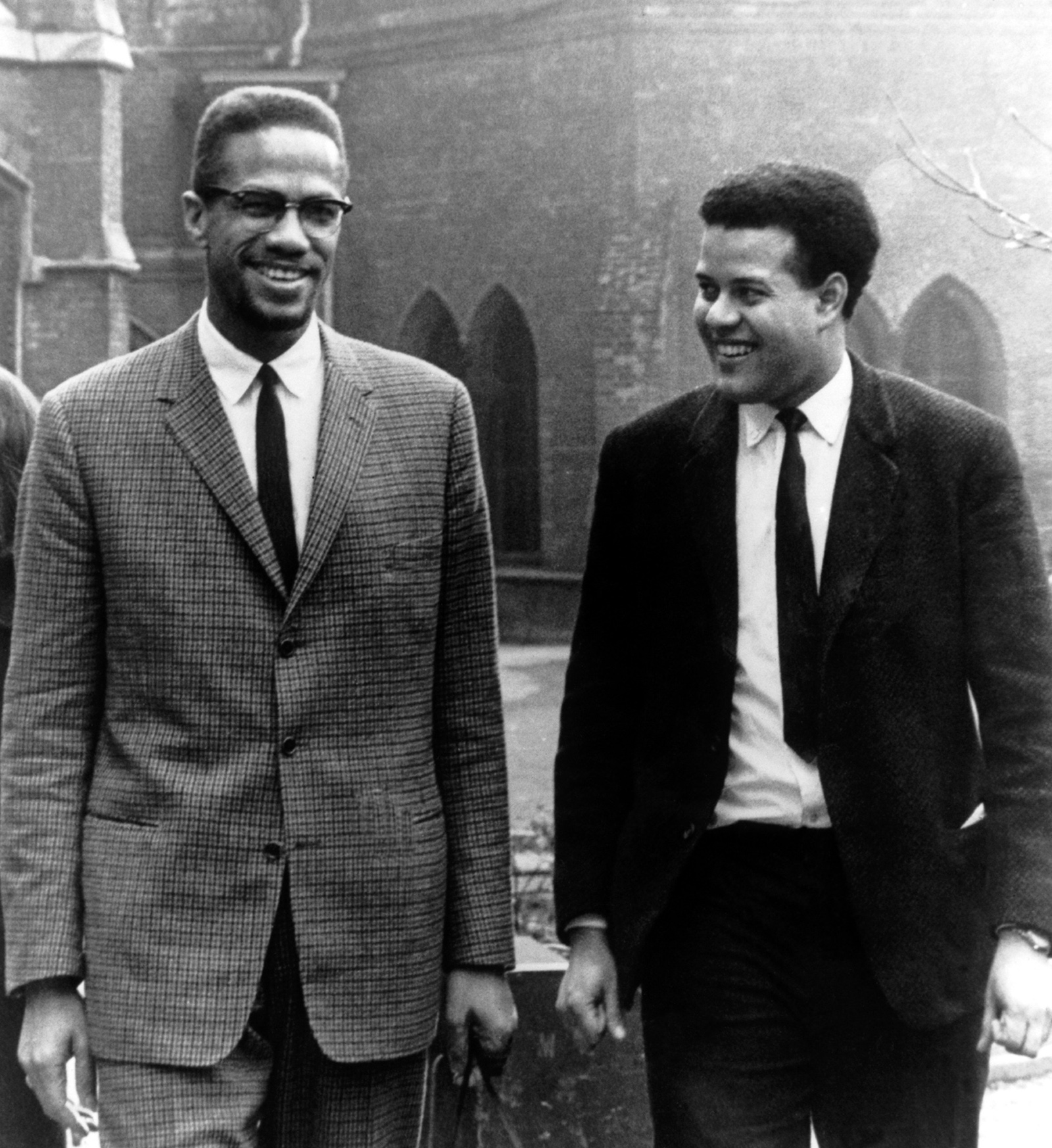

Malcolm X’s trip to Smethwick was not his first time in the UK. A few months earlier, in December 1964, he was invited to address the Oxford Union. There, he met a young British-Pakistani student who would become a leading figure on the international left.

Tariq Ali went on to recall the Oxford Union debate in his autobiography Street Fighting Years: “His speech was, by common agreement, the most brilliant to have been heard in that hall for decades.” Even Malcolm X’s critics conceded that he was a skilled speaker, able to captivate the most hostile of audiences. He used his time at the Union to remind the assembled crowd of Britain’s historic role in the slave trade and how, through colonialism, western nations had built their wealth on the back of the Global South.

The next day, on 3 December 1964, he went to Manchester University. Jane Thompson, now 79, was one of the hundreds of students who heard him speak. “I remember an amazing and powerful orator who opened up my eyes to racism,” she recalled.

“I have never forgotten his resounding words, ‘My ancestors did not come to America on the Mayflower. They came on a slave ship.’ They echo in my head to this day.”

Malcolm X’s speech added another dimension to Thompson’s view of the world, already shaped by the trade union and anti-apartheid movements. “We had no internet to inform us, so we read, attended meetings and listened to interesting people,” she said.

As part of a tour organised by the newly formed Federation of Student Islamic Societies, Malcolm X went on to speak at the University of Sheffield. His lecture there is now commemorated by a plaque and portrait in the institution’s Students’ Union building.

Similarly, his 1965 visit to Smethwick was sandwiched between one lecture at the London School of Economics the day before and another at the University of Birmingham the day after. At LSE, he addressed the Africa Society, delivering a speech that the student newspaper, The Beaver, described as “brilliant rhetoric”. In Birmingham, he spoke to Muslim students and enjoyed kebabs with them at the Indian Chamon restaurant.

When Malcolm X set off from Oxford a few months earlier, Tariq Ali said he hoped they would meet again. His response stunned the young Ali: “I don’t think so. By this time next year I’ll be dead.” Those words proved prophetic. On 21 February 1965, nine days after his visit to Smethwick, Malcolm X was shot dead while preparing to address a crowd at the Audubon Ballroom in Washington Heights, New York.

Fifty years on from his assassination, Malcolm X’s visits to the UK still hold vital lessons about the nature of solidarity. At a time when societies have become increasingly divided along racial and religious lines, his internationalist message of unity in struggle remains as important as ever.

Topics

Get the Hyphen weekly

Subscribe to Hyphen’s weekly round-up for insightful reportage, commentary and the latest arts and lifestyle coverage, from across the UK and Europe