Muslim and LGBTQI+: ‘The biggest challenge is being caught in the middle’

In a photo essay marking International Day Against Homophobia Transphobia and Biphobia, Muslim LGBTQI+ millennials and Gen Zers discuss faith and coming out

–

In April and May 2023 I spoke with several young people about their experience of being Muslim and part of the LGBTQI+ community. They shared stories of hope, fear, discrimination, love and acceptance. We also discussed their experiences of faith, coming out, taboos and their relationships with family, culture and religion.

As Sara, one of those I spoke to, said: “Queer Muslim people have always existed, and always will, yet some people still refuse to believe that.”

Queer, transgender, nonbinary and other LGBTQI+ Muslim people in London are creating welcoming spaces, podcasts, creative initiatives, charities, workshops and safe communities where queerness and Islam can peacefully coexist.

According to the 2022 Census, there are more than 3.9 million Muslims in the UK and, according to a 2021 study from a UK-based queen Muslim charity, 42% of Muslim people who identify as LGBTQI+ in the UK are Gen Z or Millennials.

The people I spoke with told me that some Muslim queer people distance themselves from “traditional” cis heteronormative spaces because they are either pushed away by their religious community or family, and that sometimes their relationship with faith is compromised.

Some embraced Islam only after later accepting they can be both Muslim and queer. Some discussed the support and acceptance they received when coming out to their families and friends while others highlighted the increasing presence of support groups such as the Inclusive Mosque Initiative, Hidayah or Imaan.

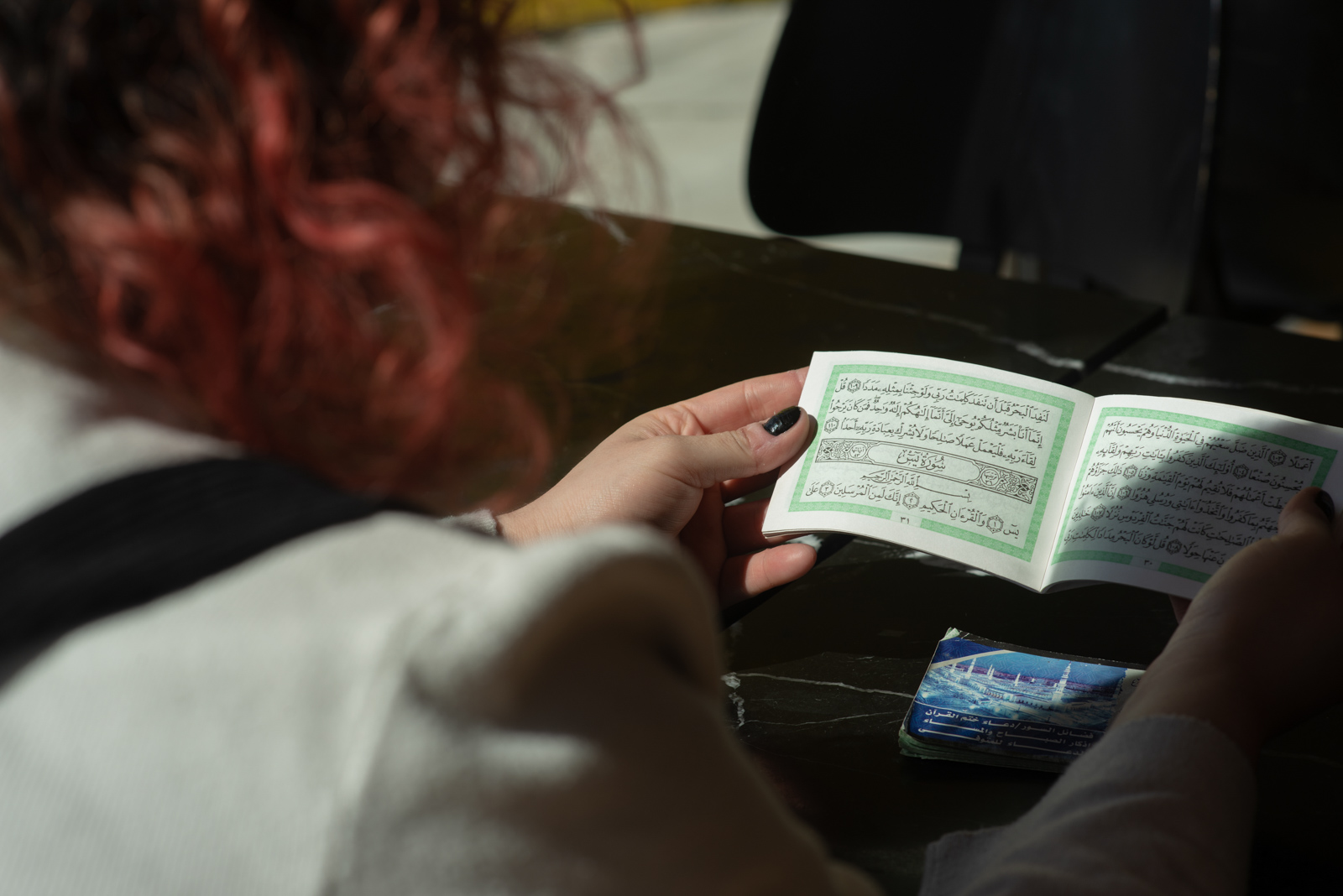

Hafsa (pictured above)

“The biggest challenge is being caught in the middle. It’s difficult to be accepted in Muslim and LGBTQI+ communities,” said Hafsa, 29, (pictured above) a prominent queer activist, who works for an LGBTQI+ charity.

“It took me a long time to find spaces where I am accepted for who I am. They include Hidayah or the Inclusive Mosque. From my experience, more Muslim spaces than LGBTQI+ spaces have been inclusive.

“Islam has gotten me through life. In Islam, we believe the community is one, but there are Muslims that I don’t agree with. It is my responsibility as a Muslim to support the planet and other people — all people queer or not. It’s part of my job, my responsibility.

“I believe in jihad, which is a struggle, balancing who I am as a Muslim and as a queer person, my struggle is explaining myself to people who don’t understand who I am.

Sara

“I am part Scottish and part Egyptian, and sometimes I feel like I am not enough of either, not Muslim enough or not queer enough,” she said. “I have come to accept that my identity is in constant flux, and I will be constantly questioning who I am.

“Lots of people have a preconceived idea of a Muslim, and sometimes I am reluctant to share my faith with some other queer people. People need to understand that Muslims come in all shapes and gender identities.”

“I have a complicated relationship with faith. I question if I should be a Muslim because there is so much homophobia and transphobia and this has led me to question the morality of my own faith at times,” she said.

Qaisar

“Hiking is a form of communion, it really helps you focus on what matters,” he said. “I came out to my mum after a breakup and it was an incredibly affirmative and positive experience. The coming out process is not the difficult part, the difficult part is then living with it.

“There are certain cis heteronormative Muslim spaces, where I wish I could feel affirmed, but I have been able to find that elsewhere. There are other inclusive spaces, such as the Inclusive Mosque, and I co-founded my own space, the London Queer Muslim Initiative, which is focused on religion, support and affirmation.”

Mufseen

Born in Brighton of Bangladeshi heritage, Mufseen moved to London to be an accountant but also to be himself. He has previously volunteered for Pride London as a finance director but now focuses on his podcast Queer Talk.

“As a gay person in the closet, you’re always looking over your shoulder in case someone from your family is on the street while you are holding a boy’s hand,” he said. “I am out now, out and proud and my family know … When I did eventually come out, it wasn’t great, but over time I’ve rebuilt relationships.”

“My relationship with my dad is very far from an ideal father-son relationship, but as you get older you accept what you can and can’t change in people,” he said. “I have really good relationships with my sisters and my brother and there is a lot of acceptance and joy there.

“A lot of queer people struggle during family events. I know when I used to go to weddings, sometimes I would take my partner as my ‘best friend’. Our entire culture is about weddings and marriage, and that’s what a lot of aunts and uncles live for.”

Asad

“I came out during the pandemic because my cousin was going to out me to my family,” he said. “I grew up in a Pakistani Muslim household, which was at times misogynistic, with traditional gender roles in place. When I came out these gender roles shattered.

“When I was a kid, my parents forced me into football. I wanted to go to drama school, but I wasn’t allowed. I was living in a shell — a mould made for me. I have greatly changed since then. I am free to be who I am and sometimes I would rather wear a skirt or a dress.”

“When I was growing up, I simply didn’t know gay or other LGBTQI+ people existed. There was a gay Muslim character on EastEnders, but when this came up, my parents would quickly flip the channel. In Urdu, the only words for LGBTQI+ people are derogatory.

“The essence of Islam is to be a good person. I will pray anywhere, and I respect the higher power, but I feel different to many other UK Muslims. I went to the mosque with an earring, because I am now comfortable with who I am, but just simply existing is a way of activism for me, and this can be draining.”

Kamala

“My first coming out was when I was 12 years old. I came out to my family as non-religious and it was a tumultuous experience,” she said. “I don’t remember much from my teenage years, as that period was filled with survival and depression.

“I came out as bisexual to my friends when I was 16 and some of them turned out to be homophobic. In 2020, I finally moved out from home, and this solidified my sexuality and my identity. I started to experiment with ‘she/her’ pronouns and finally realised that it felt like me, and after that, I came out as transgender to my friend.”

“I have been on a journey with my culture and religion,” she said. “My first chosen name was Natalie, I did it to distance myself from my culture and religion, but it didn’t feel right. I chose Kamala after Kamala Khan in the Miss Marvel series, she was Marvel’s first Muslim protagonist. After I distanced myself from religion, I got a wider view and I am once again slowly starting to embrace it.

“I am excited to be on this path of self-discovery, I am excited and happy to have found my community, and even by the hormone treatment. After years of losing friends to homophobia, I finally feel at home.”

Topics

Get the Hyphen weekly

Subscribe to Hyphen’s weekly round-up for insightful reportage, commentary and the latest arts and lifestyle coverage, from across the UK and Europe