Fasting comes in many different flavours

The rituals of Ramadan are part of an ancient tradition of restraint and contemplation that stretches across cultures, religions and denominations

–

In cultures all over the world, celebrations are closely connected with food, from wedding dinners to birthday cakes. It may seem strange to some, then, that a period marked by the absence of food and drink can be a joyous, festive time too. I am talking, of course, about the holy month of Ramadan, during which Muslims who are in good health forgo all food and drink from sunrise to sunset.

Many also try to simplify their lives, devoting more time to prayer and reflection. But fasting often goes hand-in-hand with feasting. It is common to gather with friends and family for evening iftars, breaking the fast and giving thanks to Allah for the food we eat. The season is also marked by special dishes, such as harira, a North African soup of chickpeas, chicken and noodles, and the South Asian haleem, a soupy stew made from lamb, pulses and grains, garnished with shavings of ginger, lime and fresh coriander.

In most Muslim-majority countries, markets and restaurants close during daylight hours and open only after sunset during Ramadan. Often schools are closed and society shifts to a festive, nocturnal schedule. Growing up in the UK, my earliest experiences of fasting were very different. Our home timetable changed, waking before dawn for an early breakfast, but the world around us, at school and work, ticked along as normal, filled with people eating and drinking at the usual times. The feeling of celebration only started when we got home, and the smell of warm chickpeas and frying samosas wafting from the kitchen welcomed us like a warm embrace.

For many years, that was how I understood fasting: something we did as a family, along with the wider Muslim community, but not shared by many others. At university, however, I encountered different forms of fasting from the one I had grown up with. As part of an interfaith society, I learnt about the Jewish tradition of not eating on several days throughout the calendar and that the length of those fasts varied: from sunrise to sunset for some, 25 hours for others. I remember being invited to a Yom Kippur breaking of the fast, looking around the tables and expecting to find bowls of dates and being surprised to see platters of bread instead.

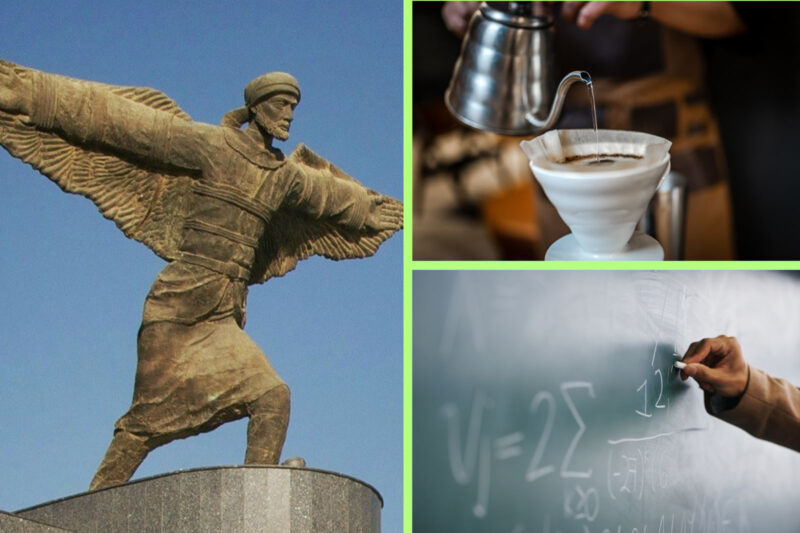

When my husband and I moved to Ethiopia in our thirties because of his work in international development, we encountered an entirely different approach. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church mandates several long periods of fasting throughout the year, including before Christmas and Easter, along with two days during each week. Around 44% of Ethiopians are part of the church, so our friends and colleagues were often fasting. But unlike the Islamic practice, which is concerned only with the timings of eating and drinking, Orthodox Christianity restricts what can be eaten.

As animal products are eschewed during fasts, Ethiopian cuisine has a delicious range of vegan foods, from shiro (spiced pureed chickpeas) and misr wot (berbere-spiced lentils) to gomen (sauteed greens) and mixed vegetable stir-fries. Soy products — chunks, milk, mince — also abound in the supermarkets of Addis Ababa. Meanwhile, every menu features fasting options, including macchiatos made with soy milk and cheeseless pizzas.

What follows extended periods of fasting — some of which are as long as eight weeks — is an unbridled celebration of meat eating. Butchers hang entire sides of beef and goat in their windows, and families go to special eateries to feast on kitfo: minced raw beef, flavoured with a chilli-spiced blend called mitmita, and clarified butter. A standing national joke is that doctors’ waiting rooms are filled with people complaining of indigestion in the days after fasting ends.

Just as there are many ways in which people and communities fast, there are different reasons for doing so. Health benefits, such as improving blood sugar levels and managing excess weight, are now attributed with increasing frequency to practices such as intermittent fasting. The spiritual motivations are also many. For some, as is seen in the Jewish fast of Yom Kippur, abstaining from food and drink is a means of atonement. In many faiths — including Islam, Judaism, Hinduism and some Christian denominations — it can also be undertaken as a form of ritual purification, or a means of spiritually and physically preparing for a significant life event, such as marriage.

The Qur’an tells Muslims: “O you who believe, fasting is prescribed for you as it was prescribed for those before you, that you may develop God-consciousness” (Surah Baqarah: 183). I find the reminder that fasting in some form or another was ordained by civilisations that came long before us especially powerful. It shows that for as long as humankind has existed, so too has the idea of balance: the need to refuse as well as to partake, to deny as well as indulge. Holding to the tradition of the Abrahamic faiths, it is humbling to see my efforts to fast in the context of a long line of others who came before me – Jewish, Christian and Muslim – all seeking greater connection to one another and to God in a similar way.

Perhaps that’s why, this Ramadan, I have found myself remembering friends all over the globe who fast at their own times and in their own ways, and hoping that this shared experience is something that can draw us all closer together.

Newsletter

Newsletter