Cologne becomes the first German city to allow mosques to broadcast the Friday adhan

While protesters and sections of the media have criticised the mayor’s decision, many Muslims see the initiative as a valuable opportunity for engagement with the local community

–

On a rainy Friday last month, imam Mustafa Kader stood before a microphone on the forecourt of Cologne Central Mosque. He was surrounded by a crowd of worshippers, journalists and a number of curious onlookers. Kader placed his hands to his ears and announced the adhan, the call to Friday prayers. As two small speakers projected his voice, the significance of the moment became clear: it was the first time in German history that the adhan had been recited outside a mosque in amplified form.

The moment was the result of an initiative overseen by Henriette Reker, the mayor of Cologne, as part of a two-year pilot project, allowing the city’s 42 mosques to cast the adhan through loudspeakers each Friday.

The spotlight was on Cologne Central Mosque (DITIB Zentralmoschee), the largest Muslim place of worship in Germany, built in 2018 at a cost of €30m provided by Turkey. But, even though 3,000 people gathered happily to hear Kader recite the adhan, the event had been met with vociferous opposition within the country and beyond.

Before Kader began to speak, a small group had also gathered across the street from the mosque to protest. Some carried banners proclaiming “No muezzin call in Cologne!”, “Public space should be ideologically neutral” and “Women, rights, freedom!” In the coming days their views would be echoed by sections of the German media, which resounded with alarmist headlines and commentary.

In an opinion piece in the German centre-right magazine Focus, Ahmad Mansour, the author and critic of Islam, warned of future consequences. “In the fight against political Islam, Germany must finally shed its naivety! The muezzin call in Cologne is not to be marketed as an expression of tolerance and religious freedom! Rather, it represents a demonstration of power by political Islam, which is primarily interested in gaining more visibility in Germany in order to influence our politics and society.”

“Cologne, not Cairo!” proclaimed Neue Züricher Zeitung, the respected Swiss German-language daily.

To many, Cologne Central Mosque’s neo-modernist, glass-fronted architecture symbolises the coming of age of the city’s Turkish Muslim diaspora

For German Muslims, allowing the adhan to be broadcast from mosques in Cologne provides a valuable opportunity for engagement with the local community. According to Abdurrahman Atasoy, general secretary of the independent Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs: “The public call to prayer is a familial sign for Muslims who have come of age in Germany. The core message of this long journey is that Muslims, with their representative mosques and with their call to prayer, have finally arrived and been accepted by society.”

Reker has also rejected the criticism of protesters and the media. “When we hear the call of the muezzin in addition to the church bells in our city, it shows that diversity is valued and lived out in Cologne,” she told a press conference on October 9, adding that the city’s Muslim citizens are a “fixed part of Cologne’s urban society”.

Cologne Central Mosque stands on the site of what was once a warehouse complex. A small and unobtrusive mosque once stood there, much like roughly 2,500 others that can be found in German cities to this day. Until recently, many of these places of worship were described as “Hinterhof Moscheen” — courtyard mosques — informal spaces fashioned out of former factories, old warehouses and even car dealerships.

The central mosque was built to offer a more visible representation of Cologne’s Muslim community. To many, its neo-modernist, glass-fronted architecture symbolises the coming of age of the city’s Turkish Muslim diaspora.

The structure’s German architect Paul Böhm is not Muslim and usually designs churches. At the time of the mosque’s 2018 opening, he said he had intended the building to suggest “openness” and “transparency” while fostering an atmosphere of dialogue with the non-Muslim community.

On a recent Saturday morning, I saw visitors drinking black tea in the mosque cafeteria. In a conference room next door a group of mainly Turkish youths were gathered for religious instruction.

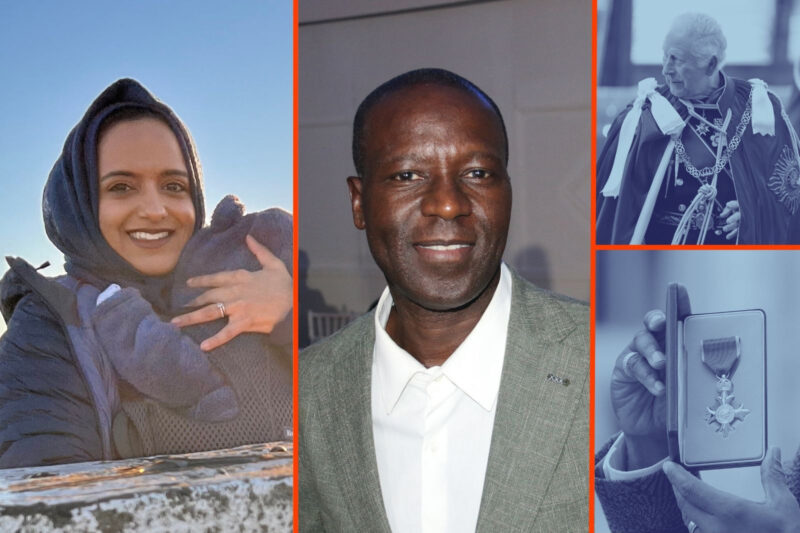

Thirty-year-old Kader is a familiar face to the citizens of Cologne and one of the most widely recognised imams in Germany. He told me he was excited by the adhan initiative and the role of his mosque.

“Our mosque has become a life-centre that embraces not only believers but also all humanity with its social and cultural activities,” he said. “It’s important not to see this space as something built of stone and concrete, but as something that was built with the great sacrifices of our ancestors.”

Kader, whose parents hail from the city of Kayseri in central Turkey, grew up in Krefeld, north of Dusseldorf. At an early age he claimed to be “fascinated by the sequence and melody of the adhan”, which encouraged him to become an imam. After graduating from high school in 2012, he left to study Islamic theology in Turkey.

“I studied in Ankara with 26 other prospective imams, all of whom came from Germany,” said Kader. “In the one-year preparatory class we improved our Turkish and Arabic and dealt primarily with the interpretation of quranic texts and Islamic jurisprudence, practised melody and led the first Friday prayers.”

A country of more than 84 million people, Germany has the second-largest Muslim population in western Europe, exceeded only by France. Among the country’s nearly 4.7 million Muslims, 3 million are of Turkish origin.

While many of Germany’s Turkish Muslims will have greeted the adhan project with enthusiasm, some will be less keen. For example, the Turkish diaspora radio station Metropol FM used to broadcast the adhan during Ramadan, but was forced to stop in 2012 after complaints by secularist listeners.

For now, though, the introduction of the adhan appears to have led to a spike of interest from visitors. Gökhan Malkoç, who has led weekend tours since 2020, told me that more people have been visiting the mosque in recent weeks.

When we met, Malkoç was showing a mixed group of Germans and foreign tourists around. By the end, the initially reserved visitors had warmed to his easy, conversational manner.

When their tour ended under the mosque’s dome, Malkoç fielded a variety of questions about Islam. When the subject of sharia law came up, he excused his lack of expertise but encouraged the curious to seek answers from one of the mosque’s more capable theologians.

Inevitably, one woman also asked about the controversy surrounding the call to prayer. “It is really no big deal,” said Malkoç. “For us German Turks, who were born and raised here, it is just a symbol of our belonging.”

Newsletter

Newsletter