Black Muslim communities prepare for a winter battle against Covid-19

Grassroots organisations in the UK are working hard to fill the gaps left by government campaigns and protect vulnerable people

On a Wednesday evening in September, an Islamic scholar named Imran Alawiye logged into Zoom and gave the elders of the Old Kent Road Mosque in south London a telling-off. Their error? Allowing themselves to feel like old people.

“It is culturally common not only to feel old, but to want to be treated as such. It’s a big mistake,” he laughed. “Just stand and say: ‘I am here, I am still playing.’ Do things, learn things, be active. Don’t surrender to counting years.”

Alawiye, a wiry, charismatic Nigerian-British man with sparkling eyes, wants older Black Muslims to enjoy their later years and to be proud of their wisdom and experience. “Our regular faces, and grey hair — all these are treasures,” he told viewers of the mosque’s social media channels.

The Old Kent Road Mosque is a vibrant hub of London’s Black Muslim community. Established in the 1960s by a small group of Nigerian students, the mosque became a hub for Nigerian Muslim refugees who arrived in the UK after fleeing political unrest. Two decades later, its congregation was boosted by new economic migrants after the collapse of the Nigerian oil industry in the 1980s. Today around 1,000 worshippers, primarily of Somali and Nigerian heritage, attend Friday prayers every week.

From early 2020, when Covid-19 restrictions prohibited large in-person gatherings, the mosque has used live online broadcasts to provide guidance to its congregation. While Alawiye’s addresses can cover everything from parenting and relationships to ageing and wellbeing, perhaps their most important role has been helping to share information and counter the spread of misinformation among Black Muslims in London.

“We were one of the first organisations to start immediately as the pandemic started. We did live telecasting, and we broadcast on all our social media platforms: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube,” explained Rashidat Hassan, a community organiser at Old Kent Road Mosque, adding that the aim is now to inform local worshippers about the Covid-19 booster programme.

Since the early days of the pandemic, widely circulated social media posts have falsely claimed that Covid-19 vaccines are not halal because they contain forbidden animal products or that they are designed to harm rather than protect recipients. Other messages stating that vaccination is against the will of Allah and that believers will be protected against infection have also spread far and wide. The origin of some of this misinformation has been traced to a Middle East-based conspiracist content hub named the Center for Reality and Historical Studies.

To combat these false narratives and provide an added line of defence for the people most at risk from Covid-19, Old Kent Road Mosque’s broadcasts have featured local medical professionals and community leaders.

“In our community we have a lot of elderly people who are very vulnerable,” Hassan said. “We try to bring everyone together and make sure we pass on the information. People have fears about the vaccine and say there are conspiracy issues, so we bring practitioners who will answer people’s questions.”

Projects like this are essential, given the shortcomings of UK government outreach to minority communities throughout the pandemic. In March and April 2020, Black and South Asian people were not only more likely than anyone else to test positive for Covid-19, they were also more likely to require admission to intensive care units and to die from the virus.

According to community leaders, while general guidance on how to stay safe was available to everyone, some groups of people were more sceptical about the virus and vaccinations than others. In addition, some faced other difficulties, including a lack of public health guidance translated into languages other than English. While outreach workers were employed to make sure disabled and other vulnerable or isolated people were protected, it was largely up to community organisations to provide culturally appropriate advice in the range of languages needed to keep all Black Muslims safe.

Government research later demonstrated that greater risk of severe infection was almost exclusively a result of social factors, rather than epidemiological ones: Black and South Asian people are more likely to work in jobs that place them at high risk of exposure to the virus and to live in situations that make social distancing harder to achieve, such as large multigenerational households.

‘When you’ve got that uncertainty that perhaps the state isn’t giving you the support that it should, then when people do start circulating disinformation’

But a dangerous subtext also began to emerge, with Black Muslim communities feeling they were being held responsible for their own higher infection rate rates and being blamed for not following social distancing guidelines. Black and Asian people were also more likely to be handed fines for breaking lockdown rules than white people.

Miqdaad Versi, a director at the Muslim Council of Britain, believes the UK government essentially left some of the country’s most at-risk groups out in the cold. “We found that outrageous and very dangerous,” he said. Hassan agrees, describing the flow of translated information and community support targeting Black Muslims as “less than a drop of water in the ocean” when compared with the efforts aimed at other groups.

Scepticism around these specific aspects of official pandemic handling appears to have led to a wider sense of mistrust that compounded the effect of misinformation. Research carried out by the Office for National Statistics and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence found that Black people in the UK and those who identify as Muslims were among the least likely to have received a Covid-19 vaccine between December 2020 and August 2021.

“When you’ve got that uncertainty that perhaps the state isn’t giving you the support that it should, then when people do start circulating disinformation, you do start listening and thinking there may be a grain of truth in it. In some senses it became a self-fulfilling prophecy,” said Jabeer Butt, chief executive of the Race Equality Foundation.

Butt and his colleagues made some attempts to engage with Muslim and other minority communities online and in WhatsApp groups, countering dangerous misinformation with factual evidence about vaccines and ways to lessen the risk of covid-19 infection. However, in his words, they were quickly “piled on” by other members.

Many of the concerns they encountered online echoed those common to the rest of the population, particularly around the speed and ethics of vaccine trials. However, the false assertion that after having the injections recipients could be tracked using 5G technology and worries about registration and vaccine passporting appeared to hit a particularly raw nerve for Black people and Muslims.

Dr Salman Waqar, vice president of the British Islamic Medical Association (BIMA), explained that these ideas were particularly potent as they cut to the heart of “who can and can’t participate in society”.

National Covid-19 case numbers are falling and, according to BIMA, the vaccination gap between minority and white communities has narrowed. The latest figures, however, show that people from Black Caribbean or Black African backgrounds are still the most likely to remain unvaccinated, at 39% and 24% respectively. People identifying as Muslim also appear more likely to be unvaccinated, although no data split by religion has been made available.

“That’s a very dangerous place to be, because that’s where complacency can settle in,” said Waqar. “The virus keeps evolving and we’ve still got a lot of unknowns around it. It could be a really bad winter.” Persuading people who have resisted for so long to get vaccinated will present an uphill struggle, he added.

“If people have not had a single vaccine by now, the amount of effort you have to put in is significant,” he said.

Butt, meanwhile, fears that the rollout of boosters could mirror previous patterns, with insufficient outreach efforts targeted at minority groups. “I wouldn’t be very surprised if we once again discover that certain communities aren’t being vaccinated,” he said.

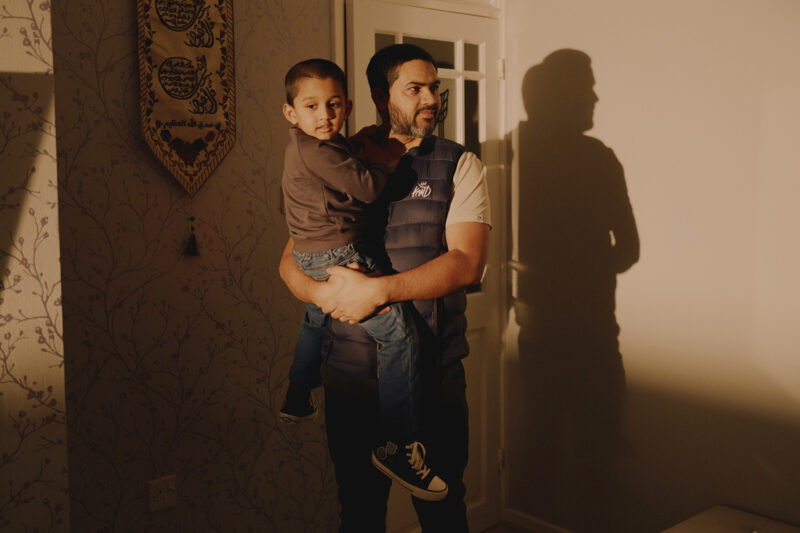

That has led to independent community groups, once again, taking the lead. In Bristol, another strategy has been deployed to convince older Black Muslims to get their boosters: grandchildren.

Bristol Youth Horn Concern has worked with young Muslims of East African heritage since 2012, using sports such as basketball and kickboxing to help protect vulnerable youngsters from exploitation by county lines drug gangs. When the pandemic hit, that mission changed.

“We had to save our community, to reduce the spread of Covid,” explained the group’s founder and director Khalil Abdi. “People were getting fake information that there was no Covid. It was coming through social media, from different countries. There was a lot of rumour that you won’t be able to have children if you have the vaccination and, targeting the Muslim community, that it’s not halal. We started tackling that distrust.”

To accomplish its goals, the organisation got young people to help pass on its message, telling them that if they got vaccinated and let their families know about it, they would be setting a good example for older generations.

Along with doorstep campaigns and open clinics hosted by Muslim doctors and nurses, the group began to shift perceptions around vaccination across Bristol’s 22,000-strong Muslim community, a third of whom describe themselves as Black African. Now it is reviving its efforts for the autumn.

“We’re getting people saying, ‘It’s not on the news any more, why are you still doing this?’” says Abdi. “We see people not from the community going into the clinics and saying don’t take [the vaccine], so we still have young people encouraging their elders.”

Newsletter

Newsletter