The man who spiced up life in the Georgian era

Sake Dean Mahomet, a 19th-century Muslim pioneer, established the first Indian restaurant in Britain

–

On a chilly morning in February 1810, Londoners were greeted by an unusual advertisement in the Morning Post. It announced the opening of a “Hindoostane Dinner and Hooka Smoking Club” in Portman Square.

Behind it was Sake Dean Mohamed, a gentleman who described himself as a “manufacturer of the real currie powder”. Mohamed told readers that he had fitted out his apartment for “entertainment in the Eastern style, where dinners, composed of genuine Hindoostanee dishes” would be served. He even offered to deliver curries to customers’ homes.

Advertisements for curry powders were fairly common in 19th-century England. The British first encountered the dish in 17th-century India while trying to establish a trading post there, and had developed a taste for it.

In 1747, the cookery writer Hannah Glasse had included a recipe for “Currey the India Way” in her book The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. By the 1800s, fashionable English homes were so keen to bring a dash of “the Orient” to their dinner tables that the spice blends could be purchased at many high-street stores.

But Mohamed was offering a different experience: the country’s very first Indian restaurant. Before he opened the doors to his stylish Marylebone establishment, 51-year-old Mohamed had led an adventurous life. Born in Patna, Eastern India, in 1759 to an elite Muslim family, he had joined the Bengal Regiment of the East India Company Army at the age of 11, following the death of his father.

He became what was known as a camp follower and servant to Godfrey Baker, an Irish cadet. A quick learner, he rose rapidly through the ranks and became a subedar, a title equivalent to captain. In 1782, he decided to follow Baker back to Ireland. The Bakers were a wealthy family and Mohamed stayed with them in their large house in Cork.

There, he fell in love with an Irish woman named Jane Daly. In 1786, facing disapproval from both their families, the couple eloped. Always enterprising, Mohamed wrote his memoirs, raising the money through public subscription. The Travels of Dean Mahomet: An Eighteenth-Century Journey Through India was published in 1794. It was the first book written in English by an Indian author to be printed in the west. It gave a colourful account of life in India, including his time in the army barracks and evocative descriptions of the Bengali cities of Calcutta and Murshidabad.

In 1807, Mohamed moved to London with his family and took up employment with Sir Basil Cochrane, an employee of the East India Company who had come back to England. Such wealthy company officials were known as nabobs and Mohamed gravitated towards them. Cochrane lived in Portman Square and had set up a vapour bath house nearby. It sparked an idea in Mohamed. He would cater to these men, serving them the best Indian food and regaling them with tales from the country they had left behind.

Since coffee houses were a popular contemporary trend, he decided to describe his restaurant as such. But that did not do the place justice. Mohamed decorated the premises with cane chairs, covered the walls with paintings of Indian scenes and set up a special room in which he offered hookah pipes to customers.

However, in March 1811, a year after the start of the restaurant, Mohamed placed the following notice in The Times, his name spelt in one of the numerous ways it was presented throughout his life:

HINDOOSTANE COFFEE HOUSE, No 34 George Street, Portman Square.

MAHOMED, East-Indian, informs the Nobility and Gentry, he has fitted up the above house, neatly and elegantly, for the entertainment of Indian gentlemen, where they may enjoy the Hoakha, with real Chilm tobacco, and Indian dishes, in the highest perfection, and allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England with choice wines, accommodation, and now looks up to them for their future patronage and support…”

In hindsight, it can be read as an appeal for backing for a struggling business. The restaurant had been expensive to open and, no doubt, remained costly to maintain. To make matters worse, the elite of Portman Square had, by that time, taken to entertaining in their own houses and brought Indian cooks to England or hired European ones who had learned how to recreate Indian dishes.

Unfortunately, the advertisement was not enough to prevent Mohamed filing for bankruptcy in 1812. Now, 210 years after the restaurant closed its doors for the final time, a green commemorative plaque on 102 George Street is all that remains of Britain’s first curry house. But it can also be seen as the forerunner of what is now a national institution, seen in every town and city across the country.

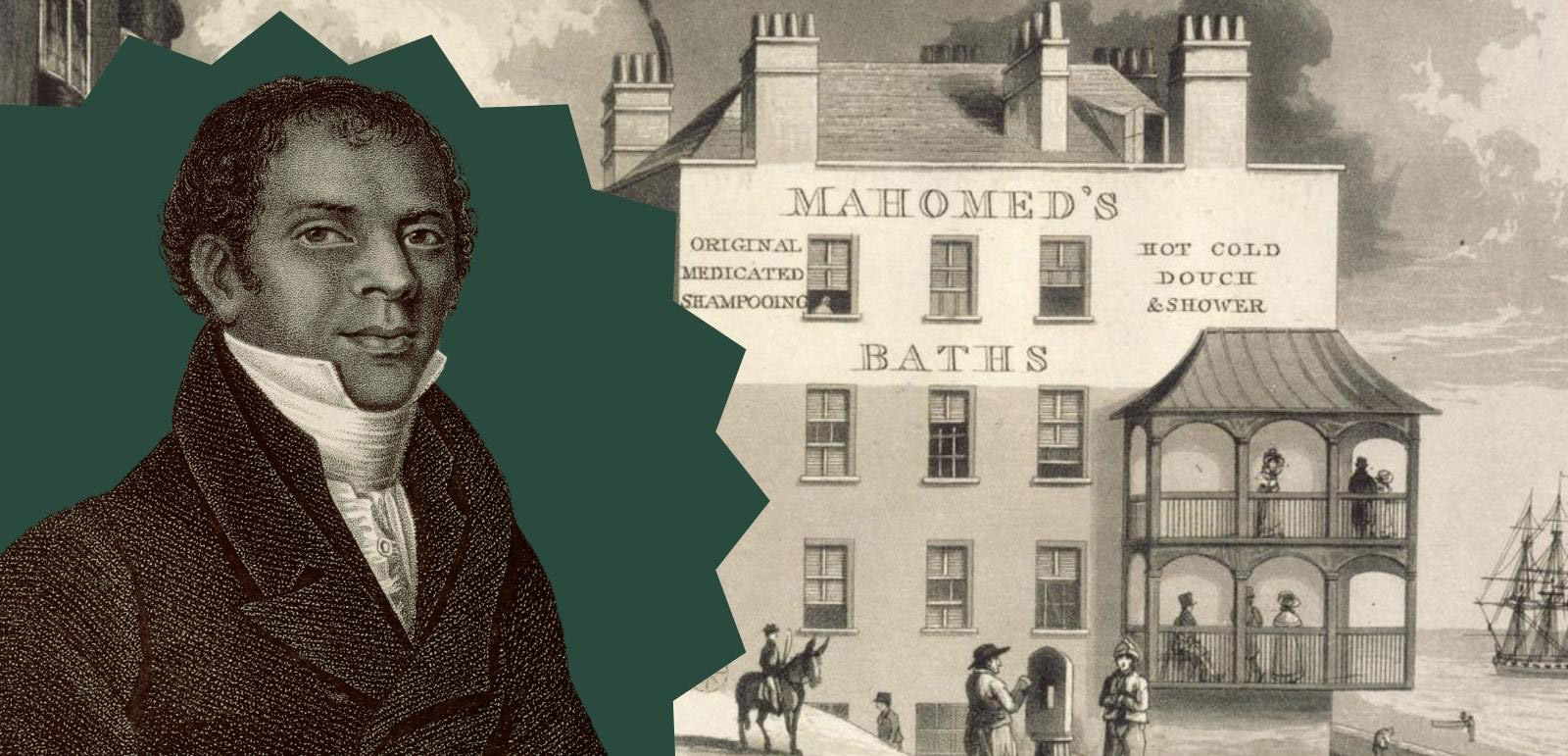

But Mohamed was not beaten. In 1814 he moved to Brighton with his family and opened Mahomed’s Baths, a spa that offered clients Indian head massages and promised to soothe their aches and pains with steaming waters containing Indian herbs and oils. Soon, he counted the Prince of Wales as a client and, in 1822, King George IV appointed him as his personal “shampooing surgeon”.

Set against the seafront in Brighton, Mahomed’s Baths was the place to be seen for the rich and famous. Its owner also became something of a celebrity, featuring in the local media, driving to the races, “gorgeous in Eastern Costume, with his pretty wife by his side and a dagger in his girdle”.

In 1822, Mohamed published a second book titled Shampooing; or, Benefits Resulting from the Use of the Indian Medicated Vapour Bath, which included testimonies from his patients and details of the benefits of his treatments.

So popular were his baths that one customer wrote an ode to him, which was published in the Brighton Gazette. Mrs Kent of Wimpole Street detailed how she was once “worn out by anguish and excess of pain” and how “hope seemed delusive and assistance vain”. Then she described how she had emerged from Mohamed’s establishment rejuvenated. Her poem ended with the lines:

“To thee, Mohamed, let a grateful heart,

Its warmest thanks in gratitude impart,

By thy great skill and unremitting care,

One has been saved that might have perished here,

Who while she feels a pulse within her veins,

Will tell thy name if memory remains.”

Sake Dean Mohamed died on 24 February, 1851, in Brighton at the age of 91. His beloved wife, Jane, had died a year earlier. The couple had five children: William, Rosanne, Horatio, Frederick and Arthur. Frederick and Arthur ran the bath houses in London.

Today, a portrait of Mohamed, dressed in western clothes, hangs in the Brighton Museum. Writer, restaurateur, bath house owner, shampooer of the royal family, he deserves to be known as one of the UK’s great Muslim pioneers.

Newsletter

Newsletter