A death in the family and the regulation of Muslim grief in France

It is becoming increasingly difficult for Muslims to find acceptance in a country where there are limited ways to be French

–

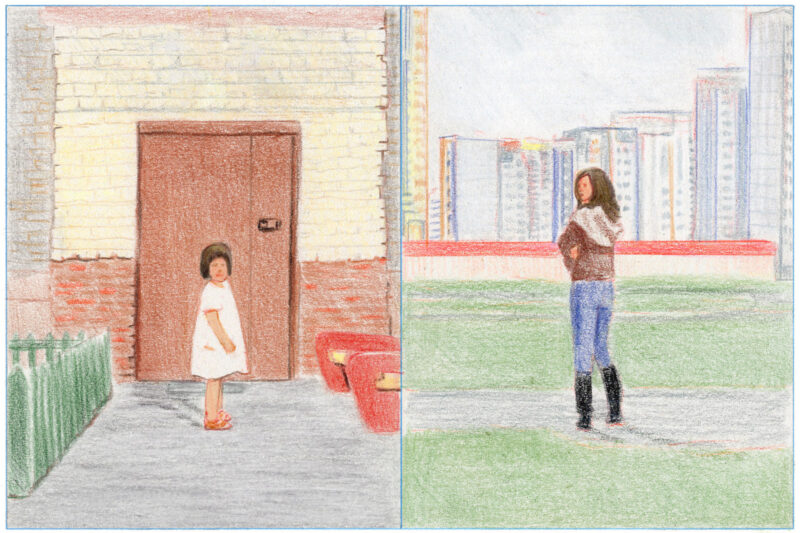

Growing up in France in the early 2000s, whenever Eid fell during the school holidays, my sister and I would travel to Algeria to spend it with family. On our arrival, my grandmother’s house in Algiers would be bursting with visitors from all corners of the country. Cousins, aunts and uncles and friends and neighbours, dressed in their best clothes, would travel to visit members of our family and celebrate Eid.

The next morning, our extended family would take our celebration to another destination: the local cemetery. Garidi’s cemetery is home to long avenues of graves bordered by cypress trees and jasmine and rose bushes growing out of tombs. The headstones are made of white stone, marble or painted concrete, common to cemeteries across North Africa. They often feature a humble plaque with the name and dates of the deceased and an invocation to Allah in Arabic. Growing up, the headstones came to complete the image of my North African heritage, Mediterranean symbols lightening the heaviness and inevitability of death.

On the days we visited, my grandmother, then in her 70s and wearing her most immaculate dress, would be the first to enter. We would follow her and some of us would distribute dates, fruit and sweets to visitors; others would pray before the tombs of people they knew and people they did not.

When my sister, Dounyazade, died suddenly in February 2021 in our hometown of Mulhouse in France, I could only imagine her resting in a cemetery in Algeria. At the age of 23, she left no instructions about how or where she would like to be buried. She was the first member of our family to die since my parents settled in France in the late 1980s. We had to quickly make a decision and friends and members of our community all gave advice during the three weeks of mourning that followed her passing. Others who had lost children warned us against a burial in Algeria, saying that we would seldom be able to visit her and cited practical issues, such as cemetery overcrowding, that were not part of my childhood memories.

I realised then that pragmatic considerations would have to prevail over emotions. We buried my sister in a local cemetery with a small but growing Muslim section, just outside of Mulhouse.

Located in eastern France, Mulhouse — which now has a population of more than 100,000 people — was once an industrial powerhouse until it was hit by the economic crises that unfolded across many parts of Europe in the late 1980s. During its heyday, some years earlier, it attracted a large immigrant population, mostly from North Africa, including my paternal grandmother.

More people followed from Turkey, West Africa and the Balkans, becoming part of what is now a well organised Muslim community. As the Muslims of Mulhouse put down roots, they soon needed access to cemeteries. Early efforts to petition local municipal authorities for a dedicated Muslim section in existing local burial grounds were successful. Muslim headstones can also be placed facing Mecca as Islamic tradition requires.

This is not a given in France — a country where, out of 40,000 cemeteries nationwide, there are only 600 dedicated sections for Muslims. Many French Muslims find themselves negotiating with local authorities hundreds of miles away in the search for an appropriate final resting place for their loved ones. I have heard accounts of family members buried far apart across a region. Others have sent the bodies of relatives back to their home countries.

Now the existence of these already scarce dedicated spaces for Muslims is under renewed threat. Last month, Marcel Girardin, an ex-elected official applied to the highest administrative legal body in France, the Conseil d’Etat, requesting the removal of any legal provision to enable their existence. According to Girardin, a separate space is “a segregationist and discriminatory view” that “undermines the essential principles of secular neutrality and equality before the law that the French Republic advocates for.” The outcome of the Conseil d’Etat’s decision is uncertain, though it is unlikely that they will decide on a ban.

Every country has its own funerary traditions. As French Muslims, ours are still in the making

While our local cemetery in Mulhouse does provide a section dedicated to Muslims, we quickly realised we were not free to install a headstone like those I remember from my youth in Algeria. No funeral home offered a simple white plaque and none was ready to write her name in Arabic. Our requests were often dismissed as not appropriate for the French weather, or deemed unfeasible by funeral home owners who wanted us to choose a headstone from their existing catalogues.

The drive to standardize Muslim burials can be jarring. Funeral homes offer to Muslims monuments in the same grey, black and sienna granite used for everyone else. While they often make one concession — Islamic crescent shapes — they also incorporate elements never seen on the other side of the Mediterranean, such as statues of angels or birds. The Muslim sections of cemeteries across France are full of these hybrid headstones: different to the others but, at the same time, sharing little in common with those found in North Africa, Asia or the Middle East.

Every country has its own funerary traditions. As French Muslims, ours are still in the making. Yet, instead of inclusive dialogue with authorities and the companies that provide burial services, we are offered a series of compromises, from limited spaces to a narrow choice of headstones. The restrictions mirror other aspects of French Muslim life, including the banning of burqas in public in 2011. Even in death, the French state regulates our grief.

Where and how we are buried will be important markers of identity for my generation. How will we, as French Muslims, reconcile our attachment to our roots and ancestors with the pragmatic issues that surround death? More importantly, it is becoming increasingly challenging for Muslims to recognise, commemorate and celebrate their dual identities when lawmakers make it painfully clear that there are only limited ways to be French. If we are not permitted to be buried in accordance with our traditions, will we have to leave the country we grew up in?

More than a year after her passing, my sister’s headstone is still a temporary wooden marker. So it will remain until I can find a way to honour her in the way she would have desired, with a white headstone, like my grandfather’s. The one that she and I often kissed on the second day of Eid, among the cypress trees in Algiers.

Newsletter

Newsletter