‘I was told I looked like I worked with bombs’: experiences of workplace Islamophobia

An exclusive Hyphen poll has revealed high levels of anti-Muslim discrimination in people’s working lives. Here, we talk to a number of individuals about how it feels and what needs to be done

IT consultant Adil Mirza was at work at an international financial institution in London when he heard someone in the office kitchen say that “the reason there are no knives here is because you might offend a Muslim and they’ll cut off your head.”

On another occasion, 44-year-old Mirza heard similar anti-Muslim rhetoric when his employer introduced halal food options. “When the canteen at work started serving some halal dishes, there were anonymous comments left in the suggestion box that said, ‘There is no place in this company for backward practices.’”

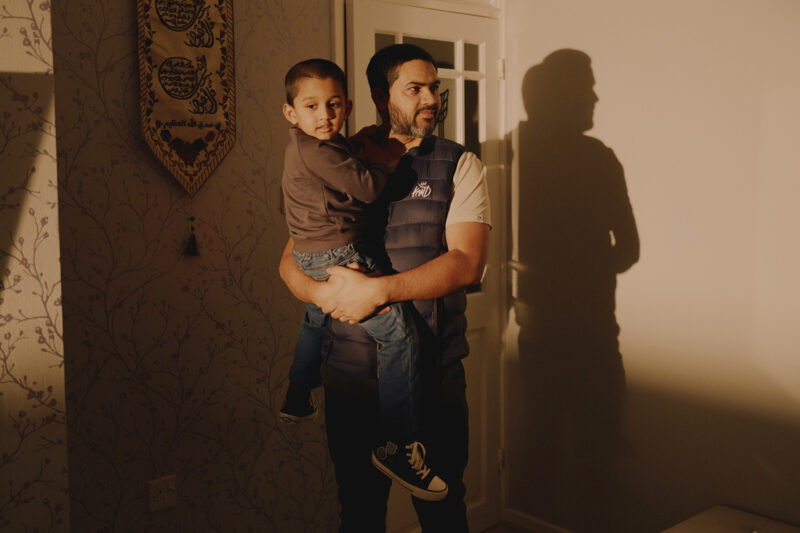

Mirza, who always wears a suit and tie to work, says he has seen and heard numerous incidents of Islamophobia during his time working for some of the world’s largest financial institutions.

And he’s not alone.

An exclusive new poll conducted by Hyphen has found that seven in 10 UK Muslims have experienced some form of Islamophobia in the workplace. The poll, carried out by Savanta ComRes, surveyed 1,503 UK Muslims and revealed that most instances of Islamophobia occurred when engaging with customers, clients or external people (44%), at work social events (42%) and when seeking promotion (40%).

Hyphen’s findings echo the experiences of prominent British Muslims who have also come under fire for their faith. London’s Mayor was called a “gay Muslim terrorist” by a Twitter user in 2018. Nusrat Ghani, a Conservative MP, has stated that she was sacked from her ministerial role as under-secretary of state at the Department for Transport because colleagues felt “uncomfortable” with her “Muslimness”. Meanwhile, Oscar-winning actor Riz Ahmed has described the movie business as “the Islamophobia industry”, citing its misrepresentation of Muslims.

While the term Islamophobia doesn’t have a legal definition in the UK, in 2019 the All-Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims stated that “Islamophobia is rooted in racism and is a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness.”

Zara Wahid, 40, believes it was her “Muslimness” that led to her own experience with Islamophobia.

“The thing is, it was never direct, but it’s always felt,” she explained.

After studying pharmaceutical sciences, Wahid, who wears a hijab and dresses in loose-fitting clothing for work, joined an international pharmaceutical company headquartered in London. “It was meant to be my dream job. I was working as a scientist in research and development, and I was there for 14 years,” she said, speaking from her home in Surrey.

‘It leaves you with a sense of imposter syndrome’

Wahid, who was made redundant in 2017 and now works for another company, added: “I watched as colleagues and those with less experience were getting the promotions, sent on work trips to represent the company, travelling for training courses.

“In 14 years, I was only promoted twice, and that was to pull my salary in line with others, it wasn’t for recognition of my hard work. Others were put on masters programmes, paid for by the company, but my requests made over years and years and years were never accepted.

“It leaves you with a sense of imposter syndrome,” she said. “I always felt, maybe I am actually just not good for the job.”

Wahid said that the Islamophobia she experienced felt like a form of abuse. “I feel like I had PTSD after that. It’s actually a little traumatic bringing this all up again because it was after I left, I realised I was living a life of some type of abuse.”

“Covert Islamophobia”

Muslim women who wear modest clothing say they are quickly defined by some of their colleagues because of their attire. Wahid said that she thinks her choice of clothing, along with not choosing to socialise in bars or places where alcohol is served, contributed to the way she was treated.

“I think it’s covert Islamophobia, but it’s hard to prove,” she said.

“There was a friend of mine, another Muslim woman, who wasn’t clearly identifiable as Muslim. She was sent to represent the company on training trips abroad and promoted many times — but after she married and changed her dress code, she started wearing hijab too, I noticed the promotions stopped.”

Not all incidents of Islamophobia are experienced by those who are visibly Muslim.

John Stevens, 48, is English and was a recent convert to Islam in 2003, when he faced his own experience of Islamophobia that culminated in a violent attack.

It happened almost two decades ago, when he was training to become a teacher.

“I’d just moved to Slough from Norfolk and was working as a religious education teacher.”

After a period of extensive study of different religions, Stevens decided to make the declaration of faith, known as the shahadah, and converted to Islam.

Stevens told his housemate, who happened to be the head of the religious studies department at the secondary school where they both taught, of his change of faith.

The reaction he got was not one of support or understanding.

“It started off with little jibes. He’d make comments. It was just after 9/11 and I remember references to Bin Laden would be dropped in.”

The abuse rapidly escalated to harassment.

His housemate would place strips of raw bacon across the door handle to his room. He would also purposefully play loud music to cause disruption just as Stevens would start his prayers.

“He’d try to slip alcohol into my drink, and he’d invite girls back to the house, encouraging them to sit on my lap. It was unwarranted and uncalled for.”

The abuse culminated when Stevens’ colleague told him, in front of other teachers at the school they both worked in, that he wasn’t a “proper teacher”, as he was still training, and that he’d only converted to gain favour with the Muslim students around him.

Soon after, at a social event, he called Stevens “disgusting” for becoming a Muslim, and then punched him in the face.

Stevens said that the harassment only ended when he left both his job and the home he once happily shared with his colleague.

British Muslims interviewed for this story said that other forms of abuse are often laughed away, but the damage done is immeasurable.

Sheymaa Nurein from east London experienced Islamophobic comments when she was made to wear a transparent visor as part of her employer’s Covid safety requirements when she returned to work as a guide at one of London’s historical attractions.

“I was told, ‘You look like you work with bombs’ and ‘You look like Gadaffi’s bodyguards’ by older colleagues at work,” said the 24-year-old.

Nurein told me she scanned the room looking for support, but instead saw colleagues laughing and nodding in agreement at the “blatant expressions of Islamophobia”.

“I wasn’t shocked, it’s sad to say. I’ve become accustomed to discrimination and prejudice at work.”

Diversity and inclusion training

Hyphen’s poll found that Black Muslims cited the highest incidences of Islamophobia in the workplace (76%).

Soukeyna Osei-Bonsu is the CEO of the London-based Black Muslim Forum. “I’m not shocked by the findings of the poll. Muslim Women in general bear the brunt of facing Islamophobia,” she said.

“Black Muslim Women have intersectional identities and look so starkly different to what the normative western person looks like. It pushes them to sit at the bottom rung of the work ladder.”

Both Mirza and Nurein say they have little confidence in reporting Islamophobic incidents to their bosses at work.

“How can I report it to them, when they are the ones who have established an environment that has made staff comfortable to be openly racist, Islamophobic?” said Nurein.

But some British employers are beginning to wake up to the realities of Islamophobia in the workplace.

Large multinationals such as Ernst & Young, HSBC and PwC have their own diversity and inclusion schemes, starting from the recruitment stage to training days, during which experts educate staff and provide tools and strategies to guard against incidents occurring.

Organisations such as Leeds-based Inclusive Employers offer diversity and inclusion programmes, including Islamophobia awareness training, to corporate organisations.

Osei-Bonsu believes that education is critical to reducing Islamophobia.

“I used to think it was up to us to protest and educate others, but now I realise we shouldn’t be the ones educating,” she said.

“The onus is not on us to train people on how to treat us. The advocacy should come from people in positions of privilege, white privilege. It’s up to them to change the narrative, to educate, start dialogue, influence policy.”

Some names have been changed

Newsletter

Newsletter