Mustafa: ‘All I can do is remain as sincere as possible in the midst of all this madness’

The Canadian-Sudanese folk artist on his stunning new album Dunya, and how music should be a vehicle to speak out against injustice

–

“My whole life I’ve been right on the edge of an end,” reflects Mustafa. “As a result, I guess I have a really hard time believing I’m going to live a long life. I still don’t fully believe that right now.”

The 28-year-old musician, Mustafa Ahmed, is speaking over the phone from Paris, where he’s preparing for an upcoming show to promote his stunning new album Dunya. Mustafa delivers his words carefully as he reflects on his childhood in Toronto’s infamous Regent Park neighbourhood — a housing project that’s long been defined by gang violence, and is a narrative the artist touches on throughout this folk-inspired record.

“I’m not afraid of death at all,” Mustafa says. “I’m actually really curious about it.”

Previously known as Mustafa the Poet, the Canadian-Sudanese artist initially found peace in writing verse as a child — his poem A Single Rose won so much attention that a 12-year-old Mustafa was profiled in his local newspaper. He says “writing poetry was always an escape” from the chaos of violence that surrounded him and other young men in the community. This poetic lens naturally evolved into music creation.

Mustafa’s work is so deeply embedded in his own experience, using songwriting to encourage his generation to embrace stillness and, ultimately, live lives away from the tragedies of gang violence. Just last year his 36-year-old brother Mohamed was senselessly and fatally gunned down in downtown Toronto. Back in June 2018, the rapper Smoke Dawg (real name Jahvante Smart), who was a member of Mustafa’s Halal Gang musical collective, was also shot to death. Mustafa says these events triggered anxious thoughts and a mind more preoccupied with examining the afterlife than embracing a burgeoning musical career — the artist won a Grammy in 2019 for his songwriting work on pop giant The Weeknd’s Starboy album, and has also earned co-signs from megastars like Drake and Daniel Caesar.

“I’ve lost so many of my friends,” Mustafa says. “Society’s systemic horrors have been chipping away at their potential to live out a long life. I do think we need more music that tells them to stay inside. I want my people to prioritise their joy and to create clearer boundaries for themselves.”

Mustafa, who draws on his Muslim faith in his songwriting, continues: “I believe in a judgement day and a day of reckoning, where all the good things we’ve done are accounted for. We finally feel freedom through the reward of an afterlife.” But still, he says: “I need to discover an urge and a want to live. That’s what I’m fighting to find.”

It’s a perfect description of the wounded beauty present on Dunya, which translates from Arabic to “the world in all its flaws”. Tonally, this follow-up to 2021’s When Smoke Rises feels like sunlight peeking through gloomy clouds, with highlight Name of God juxtaposing intimate vocals and a bright acoustic guitar melody. Confessional lyrics, such as “I don’t blame you for losing your heart” from the autobiographical track What Happened, Mohamed, suggest the artist is conversing with his brother’s wandering spirit, hoping forgiveness can help cushion his passage into paradise. Even at his most grief-stricken, though, Mustafa never loses hope (“I just want to get better”, he sings in Name of God).

Mustafa has found a way to combine the elemental sensibilities of a folk singer from Laurel Canyon, California – Joni Mitchell is his hero – with a cutting gangsta rap flow. Mustafa insists “it’s all about that contrast” of folk and hip-hop, agreeing there’s something fascinating about taking the aesthetic of predominantly white new americana folk stylings and injecting it with a street life perspective. “By singing about difficult subjects, I want to make those difficult conversations about grief feel less polarising.”

On paper this style shouldn’t really work at all, but the fact it does is a reflection of Mustafa’s relatability. While some of his Toronto-based musical peers mask their regional accents on songs, Mustafa believes listeners can better connect to him as he embraces the local dialect and its defining colloquialisms, such as “fam”. He explains: “Sometimes, if you want to make it big, you feel like you have to sound like someone else, right?

“You become something that you’re not. When that becomes too difficult of a burden to carry and you finally try to return back to your roots, you’re too far gone and you can’t find a bridge back to yourself anymore. It’s important I stay true to Toronto, always.”

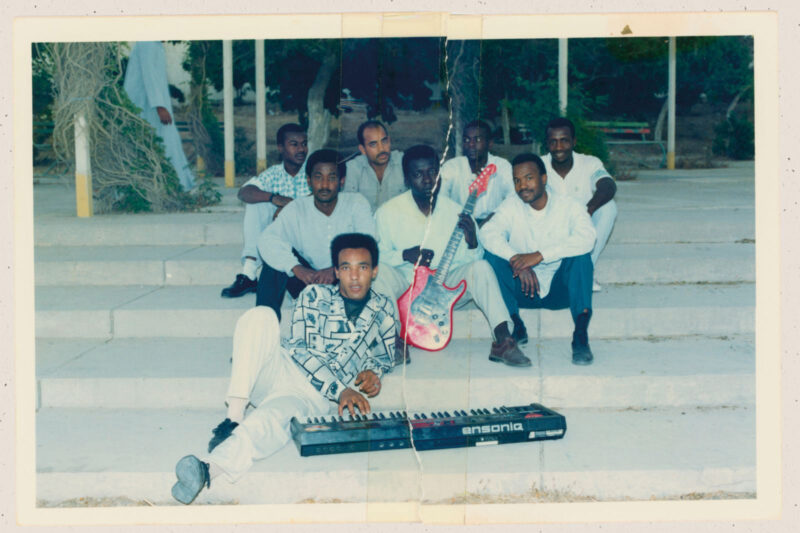

This new record also pays tribute to Mustafa’s ancestry, utilising field samples of children’s choirs and traditional instruments, including the Sudanese tambour, brought back from travels to Sudan. “I feel a responsibility to my lineage,” he says. “But I also don’t think that just because I’m performing on big stages my perspective is any more important than say my great-great-grandfather, who used to perform music in a village of only 100 people.”

Mustafa has consistently used his music to speak out against injustice, and within the solemn sitar harmony on Gaza is Calling, he urges the oppressed to defiantly fight hatred. This isn’t the first time he’s spoken up for the rights of Palestinians — back in July, he teamed up with War Child UK for a one-off London festival, including performers such as FKA Twigs, Earl Sweatshirt and Yasiin Bey, to raise aid donations.

Mustafa admits he’s felt disappointed by just how apolitical many pop stars have been about the escalating situation, critiquing the general lack of protest music that has emerged in response to Israel’s ongoing occupation and war.

“A lot of these artists have given up their integrity in exchange for popularity and deification. They’re narcissistic and so many of them suffer from this inability to feel an actual visceral empathy for anybody who doesn’t have money. Those delusions will catch up to them in the end. We’re seeing a change in the tide. There’s millions of people around the world protesting and speaking out against what’s happening in Gaza. It’s amazing to see.”

Mustafa ultimately wants to create music that inspires young people to live longer, particularly those who live amid gang violence across the world’s inner cities. Yet, at the start of our conversation, he spoke about an inability to ever picture himself with grey hairs. Is there a fundamental contradiction at play? “Sure,” he agrees, “but I literally can’t picture myself at 40. I guess there’s a possibility I will make it that far. I hope so.”

He pauses: “All I can do is remain as sincere as possible in the midst of all this madness.”

Mustafa’s Dunya is out on 27 September on the Jagjaguwar label.

Newsletter

Newsletter