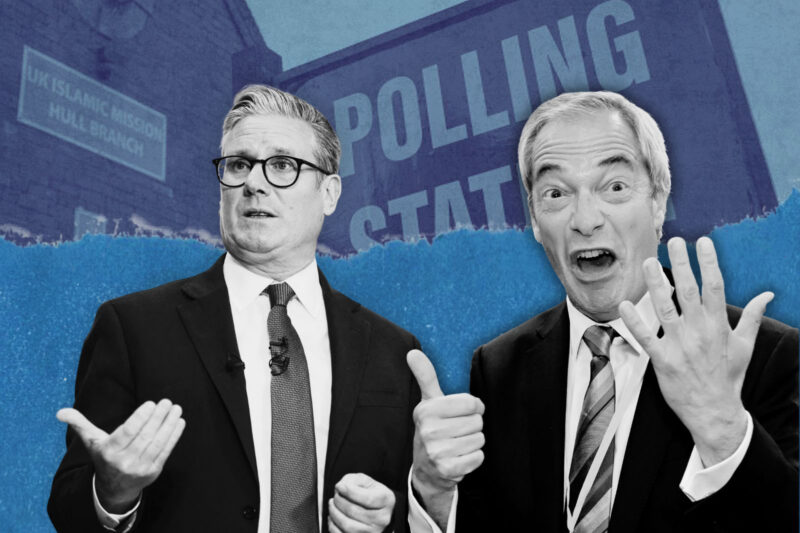

The UK’s political parties have failed to speak up about how they will address structural racism

The focus on legal and illegal immigration pushes aside the everyday problems facing Britain’s Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities

–

On 4 July, the nation will head to the polls to vote for the next government. The election follows the Covid-19 pandemic which disproportionately affected our Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities. The past five years also curtailed the largest global civil rights movement since the 1960s after the murder of George Floyd.

All the leading parties have shared some commitment to race equality in their manifestos. The Liberal Democrats commit to developing a cross-government race equality strategy; Labour suggest they will pass a new Race Equality Act; and the Conservatives suggest they will tackle racial inequality in the criminal justice system. However, all three main parties have so far failed to speak up about how structural racism will be addressed effectively. This has been accompanied by a failure of the mainstream media to scrutinise the limited manifesto commitments.

While there has been some attention on racist, antisemitic or Islamophobic comments by candidates or canvassers in the wake of the ongoing crisis in Gaza, this rarely leads to a discussion on how policy changes will tackle racial inequality. For instance, what difference the ethnicity pay gap reporting will make to workers from Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities, as the majority do not work for employers to whom it will apply. Instead of scrutiny, we have seen a feedback loop which centres immigration at the heart of debates. This discourse pushes aside the everyday problems facing Britain’s Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities.

The manifestos fail to address the shorter life expectancy faced by people with a learning disability from Black, South Asian or minoritised ethnic backgrounds: our research shows that the average age of death is 34 years old, compared to 62 for white Britons. They also ignore the persistence of poorer experiences for Black and Asian women during pregnancy, resulting in a significantly higher risk of maternal death.

The failure to adequately address the impact of racism is not surprising. The experience of the pandemic is illustrative. While the distressing news about the disproportionate deaths of healthcare workers from Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic backgrounds initially led to the publication of two Public Health England reports, many researchers, academics and campaigners had already warned that these communities were at greater risk of infection owing to their jobs, inadequate or cramped housing conditions and the lack of available support.

At the time, the policy response did not consider any of these risks, even though we knew that many of the jobs that people from these communities did, including working in healthcare and public transport, could not be done from home. People were told to self-isolate if infected, even though we knew people of Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic backgrounds were more likely to live in overcrowded conditions or in high-rise blocks.

Perhaps one explanation for current and past failings is the response of parliament in addressing racism. While accurate numbers are difficult to produce, it is likely that we have just had the most ethnically diverse UK parliament in history. Since the election in 1987, in which four Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic Labour MPs were elected, there has been a significant increase in the numbers across all the three main parties. It is probably also the case that this last parliament has seen the most ethnically diverse government and cabinet. At various points in the past three years all the major “offices of state” were held by someone from a minority ethnic background.

But the rise in ethnic diversity across government has not led to action in addressing racial inequality. For example, we have seen multiple failures in acting on the recommendations to tackle systemic racism ranging from the government-commissioned independent review of the 1983 Mental Health Act and the inadequate implementation of the 2020 Windrush review.

Instead, some of the actions taken have made racial inequality worse. A case in point is the two-child cap on benefits imposed in 2017. Several organisations, including the Church of England, have highlighted the disproportionate impact on children of ethnic minority backgrounds, and how it has exacerbated poverty. An Institute of Fiscal Studies analysis estimated that 43% of children in households with one adult of Bangladeshi or Pakistani origin (400,000 children) would be affected by the policy when fully rolled out, compared with 17% of children in other households. Worryingly, the Labour party has refused to commit to repealing this legislation if elected.

Perhaps this is not the paradox that it appears to be. If we start to examine the personal histories of MPs of Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic backgrounds across all parties, we may have secured ethnic diversity, but not experience. Few appear to have experienced poverty in their childhood, and more are likely to have been privately educated. They are also more likely to have studied at university and unlikely to have experienced poverty or housing deprivation in adulthood. This often means that most of the diverse MPs don’t reflect the experiences of Britons of Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic backgrounds. While experience does not necessarily lead to insight and commitment to social action, it perhaps does suggest that a more ethnically diverse government is not sufficient alone.

This raises concerns as to whether whoever forms the new government will see real progress in addressing racial inequality. If we return to the lessons learned from Covid-19, it is not better evidence that we need, but policymaking that uses this evidence to prioritise addressing racial inequality. This change should take place now, because the same inequalities that led to increased infections and deaths during the pandemic are exposing these communities to comparatively poorer economic opportunities.

Newsletter

Newsletter