‘My ADHD made me feel like I had failed God’

In recent years, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has become increasingly understood both at home and in the workplace — but the condition presents specific problems for practising Muslims

–

The most vivid memories Aisha Khan has of her childhood were the drives home from the mosque on Saturday afternoons. From those 20-minute journeys, she recalls a routine of being shouted at by her parents while stuck in traffic, each taking turns to express their disappointment in her lack of progress at Qur’an class. Khan’s mother, in particular, would berate her for her apparent inability to memorise surahs – a task deemed necessary in order for students to graduate to more advanced recitation classes.

“My mum was probably more angry that my cousins were all learning faster than I was,” Khan remembers. “Parents want to show off about their children, especially in Pakistani communities, and I wasn’t able to give them that opportunity.”

Khan tries her best to look back at that time with humour, but admits that those drives remain a painful memory. “Even when I go home to see my parents, and walk down that road, I remember all the times I left the car with tears still rolling down my face, and feeling sick,” she says. “I felt like I’d failed my parents, like I had failed God and he was punishing me. I believed he didn’t love me at all.”

Khan, 32, is now a tax solicitor in London and graduated from a highly ranked UK university. It is a life she never imagined for herself growing up. Leaving school with average grades, she remembers barely passing the first year of her law degree, in spite of the hours she had put into her studies. It was in her second year, in 2011, spending nights hunched over a library desk and struggling to memorise cases and statutes, that she began to feeling the same dread she had associated with her madrasa classes.

She consulted a mental health counsellor on campus, who suggested that her experiences were similar to students who had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and recommended that she get tested. Khan went to an NHS clinic for the test, which involved a combination of interviews and problem-solving exercises.

“I got the diagnosis straight away,” she says.

One moment of the examination stood out in particular. “After the diagnosis, the doctor explained that ADHD can make simple things that come easily to other people incredibly difficult to carry out,” Khan says. “I just kept thinking back to what my mum used to say to me: that if other people can remember how to pray and can read Qur’an fluently, then I should be able to as well; that I was making the choice to not pray because I wanted to be disrespectful.”

Stories like Khan’s are common among Muslims with ADHD, particularly those who have been diagnosed as adults. It is estimated that around 2.6 million people in the UK have been diagnosed with ADHD. The disorder itself is complex, and can be hard to classify, in part because it presents itself in different ways and is often influenced by the environment one grows up in.

On a basic level, however, people with ADHD will often report being unable to concentrate for extended periods of time, struggle to carry out and complete basic, administrative tasks and display impulsive behaviours that can make performing everyday interactions difficult. While the majority of diagnoses are still in children, the number among adults is growing rapidly, with NHS ADHD services recently described as “swamped”.

Research produced by the UK-based ADHD Foundation, has shown that there has been a 400% increase in the number of new diagnoses since 2020, while data from the NHS shows a 40% increase in ADHD-related prescriptions since 2015.

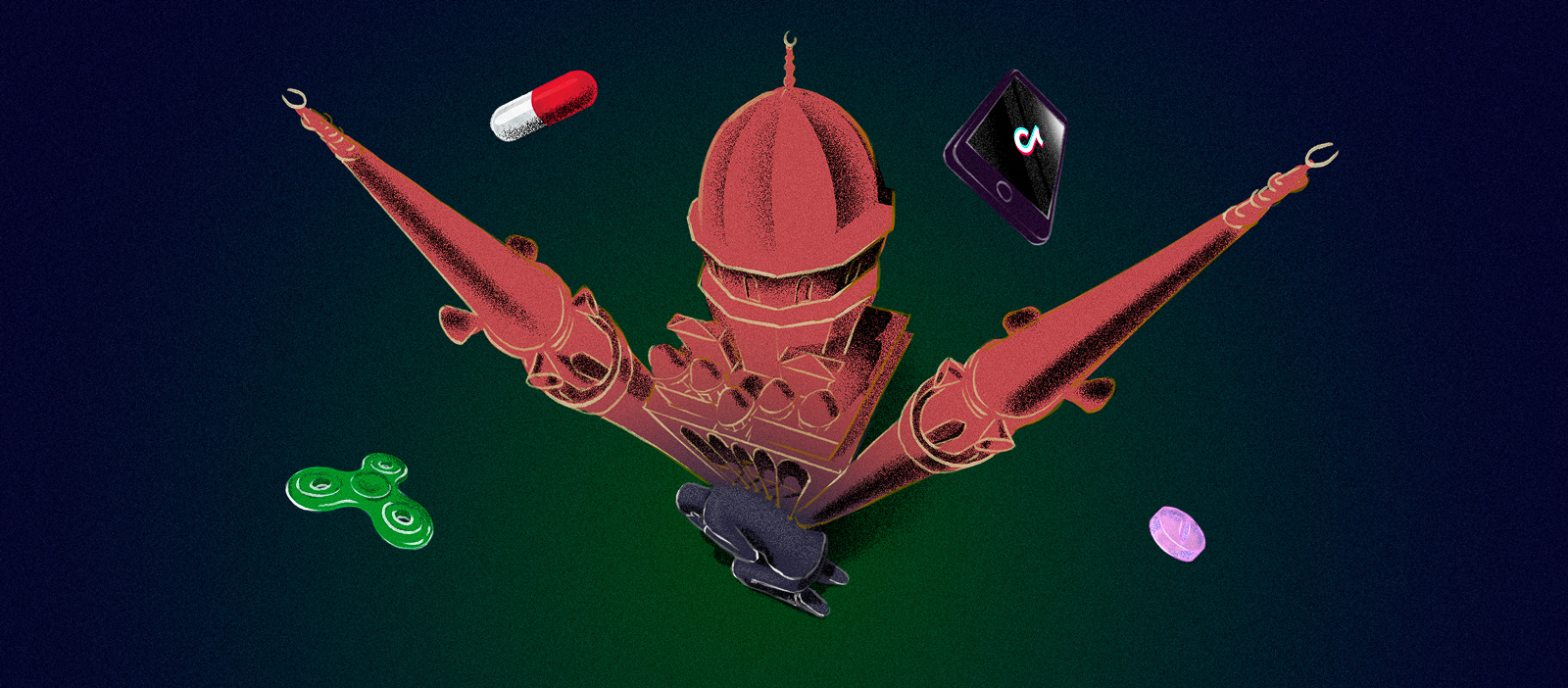

Social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok have also helped to create greater awareness of ADHD, hosting explainers and infographics on how the disorder can affect attention spans and lead to problems maintaining personal relationships. A plethora of podcasts and YouTube channels also exist, as do products such as journals, earplugs and fidget toys, designed to assist people with ADHD in social and professional environments.

Organisations such as ADHD UK are also campaigning for workplaces to accommodate employees with the disorder by offering flexible working hours and other, more specialist mental health provisions.

Despite the increased resources now available to people with the disorder, little has been done to address the spiritual issues faced by Muslims with ADHD. The majority of Muslims interviewed for this article said that while they found online content about ADHD useful at work and at home, when it came to building a better relationship with Islam — being able to concentrate while praying, or paying attention to a khutbah while sitting in a mosque — they still felt stuck.

Hamza, 26, from Leicester, believes that having undiagnosed ADHD has left him “feeling inadequate in every Islamic setting”. He describes his inability to concentrate on salah for more than two rakats, and feeling a guilt so deep that he eventually stopped practising Islam.

“Growing up as a Muslim, you’re told that if you lose concentration in prayer, it becomes invalid,” he says. “I kept losing concentration in the mosque whenever we would pray, especially at night. I remember feeling so guilty that technically, I hadn’t completed a single prayer in my entire life.”

“Guilt can be common among people with ADHD. With Muslims, because Islam is a very active religion, it’s not uncommon that feelings of shame can emerge if they are unable to pray,” says Jodie Wozencroft-Reay, a UK-based cognitive behavioural therapist and founder of Hidayah Neurodiversity, an organisation specialising in providing therapeutic services to Muslim communities.

Wozencroft-Reay adds that such feelings can be particularly acute among children and young people at the start of their religious education.

“It can be a high-pressure environment,” she says. “In some cases, the religious education that’s provided promotes the idea that God wants to punish you and that, if you don’t follow a set of rules and guidelines, you will be punished.

“If you have ADHD, it’s likely that you might struggle with a structure that is placed on you. It’s easy to feel that being unable to follow that structure then makes you a bad person, even though this was never said, by God nor in the Qur’an.”

NHS waiting lists and the absence of culturally appropriate resources mean that many Muslims who believe they have ADHD are having to seek guidance online. One popular website is the r/ADHDMuslims subreddit, where members discuss issues ranging from their experiences with medications such as Ritalin and Adderall to strategies on managing symptoms including anxiety and overeating during Ramadan.

On TikTok, Muslim creators with the disorder also share their experiences and provide bespoke guides on carrying out prayers in healthy ways. One popular video clip argues that Muslims with ADHD should read just two lines of Qur’an a day, rather than entire pages. Another, made by the American Muslim Rotimi Lademo, suggests making visual charts and placing reminders on walls to record prayers and basic tasks, such as tooth brushing and exercising.

“The growing awareness of ADHD among Muslims is a good thing, but more needs to be done to accommodate people who are struggling,” says Wajda Tabassum, a London-based Humanistic therapist who has worked with a range of neurodiverse Muslim clients.

“We need more books, websites and groups for Muslims with ADHD, as well as a greater understanding of the unique challenges they face. Right now, it’s easy to see someone who can’t focus on reading the Qur’an or who loses their attention during prayers, and for them to be called lazy.”

Tabassum says that mosque leaders need to do more to make neurodiverse members of their congregations feel comfortable, but emphasises that such measures need not be costly. She believes that simple measures — from the use of more visual imagery in madrassa classes to mosques teaching mindfulness practices, such as meditation, alongside traditional Islamic studies — could help people with the disorder .

“Ultimately, people with ADHD just want to be offered kindness and compassion,” she says. “The key is to stop them feeling guilt and shame if they are struggling with their faith. Instead, we should be helping them by showing that they can still practise the religion and that it can be adapted to fit the way that their minds work.”

Though Khan still has not memorised any surahs, she now takes Ritalin to help manage her ADHD. It has not made the challenges that come with practising her faith disappear, but she does believe that it has helped reduce the anxiety she used to associate with Islam.

“Now, when I pray, I feel a lot calmer, and even if I forget a line of recitation, I can calmly just go back and start it again,” she says.

She also credits the ADHD diagnosis with helping her to build a healthier relationship with her parents, who have apologised for their treatment of her as a child. Her aim is to make sure that other young people in her community do not have to go through the same struggles. Eventually, she hopes to teach the Qur’an in a way that is inclusive and accepting.

“I would like young Muslims who are struggling with their faith, for any reason, to know that they are accepted and that God does love them,” she says.

Topics

Get the Hyphen weekly

Subscribe to Hyphen’s weekly round-up for insightful reportage, commentary and the latest arts and lifestyle coverage, from across the UK and Europe

This form may not be visible due to adblockers, or JavaScript not being enabled.