Book by book — building a new home for Arabic literature in London

The number of independent booksellers in the UK has nearly halved in the past 30 years. A new startup hopes to reverse the decline

–

It’s early March when Maqam Books hosts its first event. The venue, a fashionable arts space in east London, has been transformed into a makeshift Arab bazaar. In one corner, a young woman is selling hand-embroidered accessories from her mother’s small business in Gaza. The walls are decorated with prints by an Egyptian illustrator, a Palestinian artist and an Algerian calligrapher, and the shelves are lined with a curated selection of Arabic-language books.

Over the course of two evenings, more than 400 people visit the pop-up. The organiser, a 28-year-old bookseller named Mohammad Masoud, mostly hovers by the entrance, greeting guests as they arrive and depart. The event, he said, is “a glimpse of what we are trying to achieve in the future”.

Maqam, which translates as “place” in English, was founded in January when Masoud launched a public campaign to raise £90,000 for a new bookshop in London. If all goes to plan, it will provide a home for Arabic-language books by South West Asian and North African authors, with a focus on engaging young readers. At the time of writing, the appeal has collected £15,000 in donations.

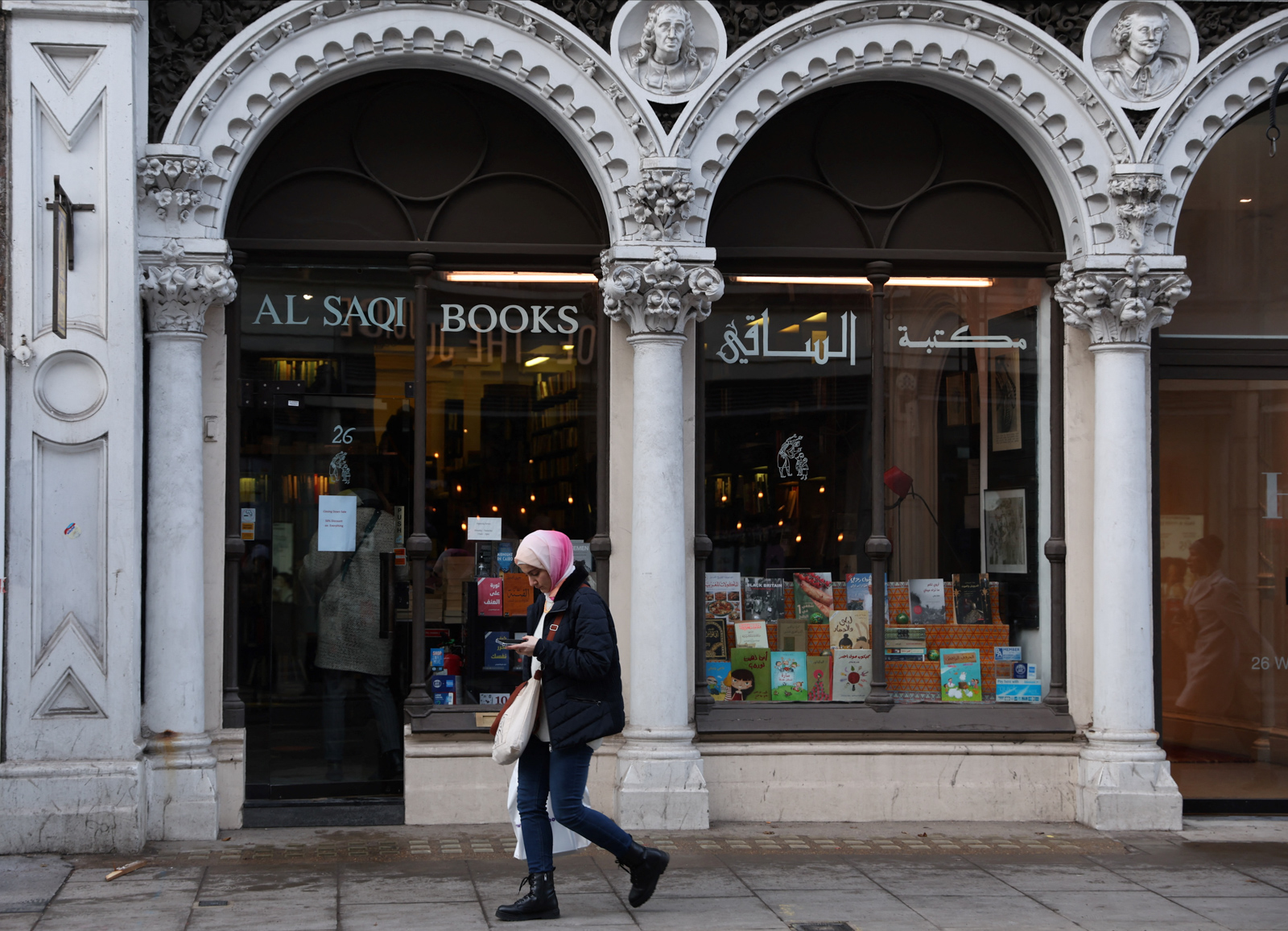

Masoud hopes to fill the vacuum left by the closure of Al Saqi Books, previously London’s oldest and most renowned Arabic bookshop, which closed its doors after nearly half a century of trading last December.

At the time, Al Saqi’s owners cited “difficult economic challenges” in a post shared to Twitter, eliciting an outpouring of grief from the loyal customer base they had built over the course of the shop’s 44 years. “A mainstay of my whole existence in London,” wrote Nasri Atallah, former editor of Esquire Middle East. “End of an era. Thank you for giving my dad and his diaspora buddies a place to go every weekend over the decades,” said journalist and author Jailan Zayan. “Each book I bought from you was an education,” wrote the poet, journalist and musician Musa Okwonga.

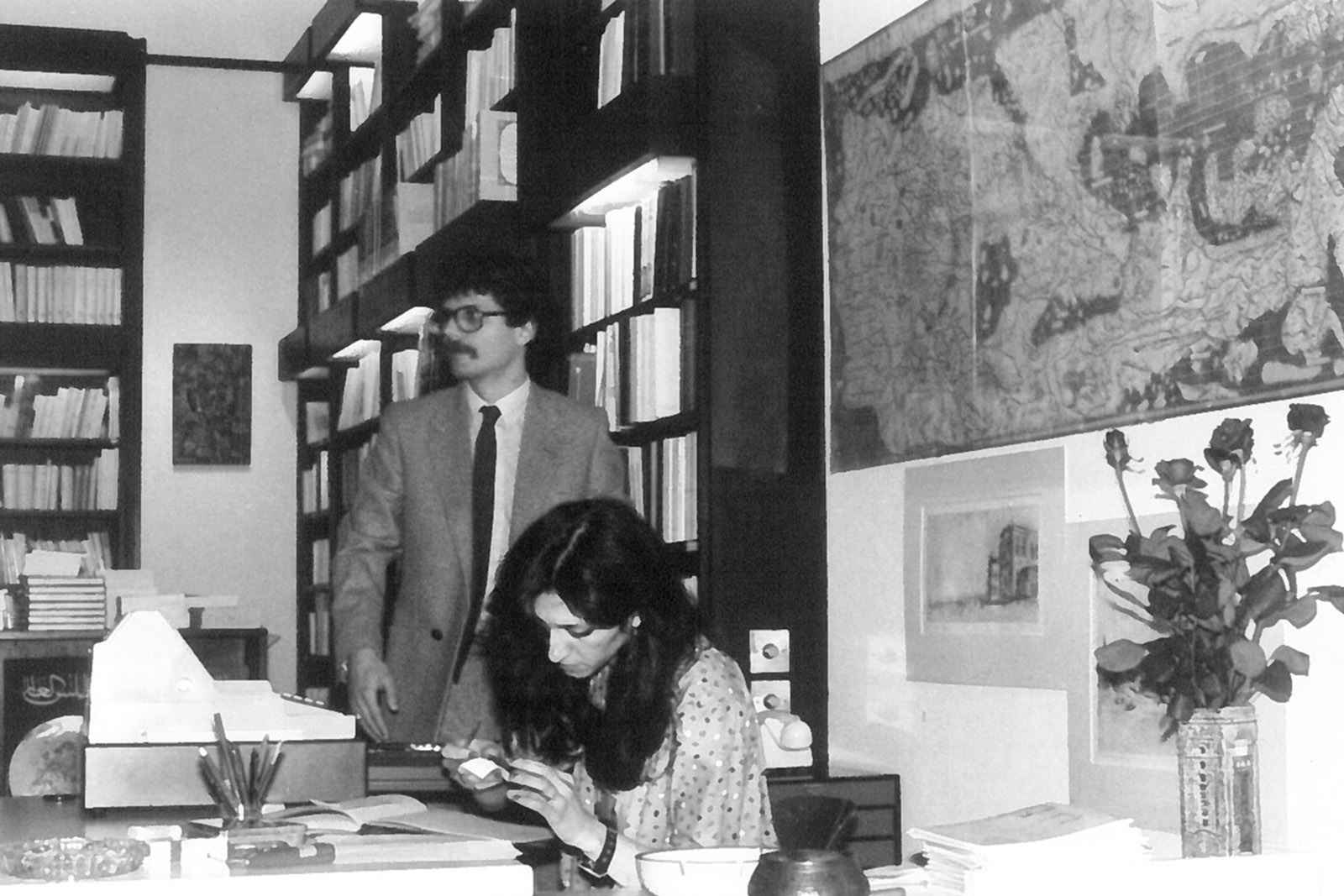

Al Saqi Books, situated on bustling Westbourne Grove in west London, was opened in 1978 by husband-and-wife team André and Salwa Gaspard, and their friend, the late author and human rights activist Mai Ghoussoub. The bookshop was established to promote the core values of openness and freedom of thought, and was intended to feel like a “home away from home” for the Arabs that visited the store, according to the Gaspards’ daughter, Lynn. She added: “It didn’t matter if you were Muslim or atheist, or what your ethnic background was. You were always welcome, and you didn’t have to justify your being.”

In the decades since its opening, Al Saqi Books became the first port of call for a generation of academics, scholars and everyday readers searching for popular and niche Arabic authors whose works were often impossible to find in mainstream bookshops or online stores.

Among them was Malu Halasa, a Jordanian Filipina author and founding editor of Tank magazine, who moved to London from the US in 1986. “Al Saqi Books brought you to the art and the music, to the people and voices of the region,” she said. “It started new and lasting conversations, and it formed the philosophy that underpins my work today.”

The bookshop stocked upwards of 6,000 titles, some of them published by the bookshop’s printing subsidiary, Saqi. The founders also often invited acclaimed writers to speak about their work, including Hanan al-Shaykh, author of the controversial 1980 novel The Story of Zahra, and Leila Aboulela, who won the Scottish Book Awards for Fiction in 2011 with her novel Lyrics Alley. In doing so, it raised the profile of Arab writers. “People like Robert Irwin of The Times Literary Supplement would come and listen to people talk, and then go back and say ‘We need to review this’,” Halasa recalled. “Now that it’s shut, that connection is kind of diminished.”

Masoud was born to Palestinian parents in a refugee camp in Amman, Jordan, in 1994. His father worked in Saudi Arabia while his mother stayed behind to raise him and his older sister. Masoud cites her for teaching him to read using books from a now-defunct publishing house that produced short stories for children in Arabic.

His mother worked at a local bank and, by the time Masoud turned 11, she had saved enough money to buy the family a home of their own. By then, Masoud was a committed reader. “My cousins still make fun of me,” he recalled. “As children, when we used to play hide and seek, they would find me, instead of looking for them, reading a book. So eventually they stopped playing with me.”

Masoud joined Al Saqi Books in January 2021, six months after moving to the UK. He remembers the two years he worked there until its closure as some of the best of his life. “I knew of Al Saqi before I moved to London, but I never dreamed I would have the opportunity to work there,” he said. “It was a beautiful time.”

Part of Al Saqi Books’ global appeal was that it stocked books that may have otherwise been banned in those Arab countries with strict censorship laws. In 2022, it debuted This Arab is Queer, an anthology of essays by queer Arab writers, compiled and edited by the UK-based journalist Elias Jahshan.

Jahshan told me that he was given complete artistic freedom on the project. “This Arab is Queer was us taking ownership of the narrative and showing that we don’t need permission to tell our stories however we want,” he said. According to Masoud, the collection quickly became one of the shop’s bestselling titles.

For Masoud, the end of Al Saqi Books is evidence of an ongoing crisis for Arab spaces in London after a number of major initiatives have shut down. In January 2022, the community hub and events venue Rumi’s Cave announced the closure of its Kilburn home, the Carlton Centre, after plans were approved to tear down the building and replace it with 18 council homes. Earlier this year, BBC Arabic, which had broadcasted from its Portland Place headquarters for 85 years, went off air as part of cost-cutting measures. “Our culture, our presence and what represents us is vanishing from a place that is actually filled with people from the diaspora,” Masoud said.

Despite these losses, there remains no shortage of appetite for Arabic books and cultural spaces in London. This year’s Arab Women Artists Now, an annual literature and arts festival in its ninth edition, had a packed schedule for the duration of March. Meanwhile, Shubbak Festival, which celebrates Arab artists, musicians, film-makers and authors from across the world, is set to return to the capital for its 11th run this summer.

But while Arabic cultural spaces continue to attract visitors, speciality bookshops have rapidly declined in numbers. The rise of e-commerce giants such as Amazon, which offer faster shipping and lower prices, has meant that many traditional bookshops have struggled to survive. According to the latest figures from the Booksellers Association, the number of independent booksellers in the UK fell by almost half in the past 30 years, from 1,894 in 1995 to 967 in 2021.

“The internet has made it very easy to get hold of things, which means every shop has got to up their game. It’s not enough any more to just have books sitting on a shelf,” said Max Scott, managing director of Nomad Publishing, a London-based publishing house with a focus on history, culture and travel books by Arab writers. “Take Barnes & Noble in the US. They worked out a way to keep customers there by opening a coffee shop inside.”

Scott said Maqam is entering the market at a time marked by a “renaissance” in Arabic literature. “A lot of money is being invested in this area. There are huge budgets chasing the promotion of books here, but currently there are limited ways to promote them.” One such example is the Abu Dhabi-based Sheikh Zayed Book Award Translation Grant, which aims to increase the number of Arabic books that are translated, published and distributed outside the Middle East and North Africa. Last year’s shortlisted titles came from Morocco, Syria and Egypt. “That’s where there’s an opportunity for a new Arabic bookshop,” Scott added.

In the case of Al Saqi Books, Lynn said the family were left with no choice but to close the shop after myriad challenges made it “untenable” to stay in business. Since launch, the shop sourced its Arabic-language books from Beirut, Lebanon, but owing to the country’s deep economic crisis — since 2019 the national currency has lost more than 98% of its value — publishers and distributors drastically upped their prices. The price of shipping a book to the UK from Lebanon also quadrupled. The Al Saqi building has since been sold to American interior design firm Hirsch Bedner Associates.

Al Saqi Books made a sizable chunk of its income from the large numbers of Arab visitors who travel to London each year, but Lynn — who still runs the publishing arm — said this customer base shrank after Brexit. “There were periods throughout the year that Arabs would travel to the UK and spend thousands on books. But they just aren’t coming here in the same numbers any more,” she explained. “Brexit has put everyone off and now they prefer to go to Europe.”

According to Masoud, Al Saqi Books became “too focused on catering to Arabs from abroad”. He wants Maqam to create a diverse community hub for Arabs in London that will generate income beyond book sales.

An online website will stock a full inventory of books, but in-store visitors will be able to peruse a curated selection of titles sourced from publishers in Qatar, Jordan, Egypt, Kuwait and Tunisia, as well as titles from Masoud’s personal library of more than 1,200 works. The walls will be mounted with artwork and photography by Arab creatives. An in-house barista will serve fresh coffee and, on weekends, parents will send their children to learn Arabic from a team of tutors.

“I want to create something that, in 10, 11, 12 years’ time, people will look at and say, ‘this place taught me Arabic’, ‘this place helped me improve my writing skills, or ‘something I read here inspired my dissertation’,” said Masoud.

The Maqam team is applying for grants from charities and private donors to reach their £90,000 goal. Masoud anticipates opening a physical location this summer — though a site is yet to be determined. The bookshop has also earned the approval of the Gaspards. Lynn praised the project, describing it as a “fantastic” undertaking that has the potential to fill a “huge loss”.

“Our predecessors did what they could. Now that they’re resigning and moving on, it’s up to young people to save what’s left,” Masoud said.

Topics

Get the Hyphen weekly

Subscribe to Hyphen’s weekly round-up for insightful reportage, commentary and the latest arts and lifestyle coverage, from across the UK and Europe

This form may not be visible due to adblockers, or JavaScript not being enabled.